The Rabbi That Started It All

When Ferdinand and Isabella expelled the Jews from Spain on 31 July 1492, they were welcomed with open arms into the Ottoman-ruled Balkans. Thus the Balkans, and particularly Sarajevo, came to be populated with Sephardic Jews to the extent that at the height of the community’s population, 20% of Sarajevo was Jewish and 10% of Sarajevo spoke Ladino as a first language.

In 1686 Ashkenazi Jews began to arrive in Bosnia and Herzegovina after the Ottomans were expelled from Hungary by the Holy League. A time of great upheaval, one man named Tzvi Ashkenazi escaped from Budapest after his wife and child were were killed by cannon fire during the Austrian invasion managed to get to Sarajevo and be appointed rabbi just in time for Eugene of Savoy to sack and burn the entire city to the ground in 1697.

Although there were certainly unfortunate incidents, Jews in the Ottoman Empire enjoyed much more safety and far more recognition under the law than those in Western Europe. Their community had significant autonomy and were given full autonomy over their own internal legal matters. They were able to buy real estate, build synagogues, and conduct trade throughout the Ottoman Empire. And in 1856, under the Tanzimat reforms, they were given full equality under the law.

Even the first synagogue of Sarajevo, still standing today, was built in the sixteenth century with a grant from the Ottoman governor of Bosnia.

But although the Ottoman Empire was more safe than Western Europe for Jews, it was not entirely safe, as was illustrated in the 1840 Damascus Affair.

On 5 February 1840, Father Thomas, a Capuchin friar, and his servant went missing. Tensions were already present between the Christian and Jewish community of Damascus, and it spiraled into accusations of ritual murder. Brought before the governor, thirteen of the most prominent Jewish citizens of Damascus were arrested on the word of a Jewish barber who had been tortured into a confession.

The thirteen Jewish citizens were, in their turn, tortured as well. Upon their arrest a mob of the local population and Ottoman authorities attacked a synagogue and burned the Book of Law.

The incident provoked a backlash within the international community – one with enough force that the Ottomans instituted an investigation and review on 4 August. Completed on 28 August, the nine Jewish leaders still alive were immediately released, and a firman (edict) was released on 4 November which declared blood libel a slander against Jews and completely banned within the Ottoman Empire.

“…and for the love we permit the Jewish Nation, whose innocence for a crime alleged against them is evident, to be worried and tormented as a consequence of accusations which have not the least foundation in truth.”

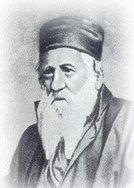

This incident had a profound effect on Rabbi Yehuda Alkalai, who had been born in 1798 in Sarajevo and began serving as the Rabbi in Zemun (on the outskirts of Belgrade, Serbia) in 1825, an effect that would end up changing the entire second half of the twentieth century. It was Rabbi Yehuda Alkalai, in the mid nineteenth century, who first developed the call to Zionism.

Alkalai served as a rabbi in the Balkans during the Serbian War of Independence, a rise of nationalism that resulted freedom from the Ottoman Empire. The Serb rallying cry of the War of Independence, which has been used ever since, “Only Unity Saves the Serbs”, drove another truth home to Alkalai – that Jews had only each other in the world, and they must work together to make sure that Judaism would survive. His writing Shema Yisrael (1834) first brought the idea of Jewish political independence a “Land of Israel” to general attention. The problem was that his idea of moving Jews to the Holy Land to bring about Messianic Redemption was considered heretical amongst Jews who believed that Messianic Redemption could come only through a miraculous event caused by God. Alkalai believed that the Jewish prayer, “Hear O Israel” should be reinterpreted, and that it actually was a call to bring all the children of Israel together. It was not a popular opinion, and no one was flocking to put his ideas into action. Many were actually quite horrified.

The Damascus Affair solidified Alkalai’s ideas. In 1840 he wrote Shelom Yerushalyim. Alkalai’s kabbalist background was prominent in this collection – he used the Kabbalah belief of the “Days of the Messiah” to predict that 1840 was the Year of Redemption. From 1840 the Jewish community would have 100 years to return to the Holy Land. If it were not done by 1939, the 100 years from 1939 to 2040 would be a time of great hardship for the Jewish people, “an outpouring of wrath will gather our dispersed.” The end result, a return to Israel, would be the same, but it would come about under much harder circumstances. Rabbi Alkalai urged a 10% tithe from all the world’s Jews to support the effort of moving back to the Holy Land.

But it was Alkalai’s 1857 writings that truly triggered the change of the world, because it was Goral al Adonai that gave a more complete picture of just how the Jews were to return to the Holy Land. It was also Goral al Adonai that Rabbi Alkalai gave to his students Simon Loeb Herzl and Jakob Herzl, the grandfather and father of the man now known as the father of the state of Israel – Theodor Herzl.

Rabbi Alkalai called for the restoration of Hebrew as a national language, for the recovery of land in Israel to be done through purchases, and for Israel to have an agricultural basis. He recommended that an Assembly of Jewish Notables be put together as a representative body of the Jewish people, to appeal to nations for help on their behalf, to help people resettle, and to properly disperse the tithes. In short, as the historic events of the Serbian War of Independence and the Damascus Affair intersected in one Balkan Rabbi, Rabbi Alkalai formed the idea of Zionism before Zionism was even an idea.

Today the Rabbi Alkalai’s synagogue is still standing in Zemun, on Rabbi Alkalai street. It is used as a nightclub, a restaurant, and a synagogue – an interesting combination that might not be duplicated anywhere else in the world. Rabbi Alkalai street is near Theodor Herzl Street, which was opened to great local fanfare by Serbia’s president Alexander Vučić and the president of Israel Reuven Rivlin in 2018.

Theodor Herzl’s grandparents are still buried in Zemun, but Rabbi Alkalai himself was able to emigrate to Jerusalem in 1876, dying on 1 October 1878. He is buried in the Mount of Olives Jewish Cemetery.

Records in Belgrade record a quote from Rabbi Alkalai, “It is easy to reconcile two states, but [hard to bring together] two Jews.” It was said in response to the lack of reaction to his idea of a Jewish homeland in Israel, and it mirrors another oft-saying in response to the feud between the last two Jews of Kabul, “If two Jews are in a room, there will be three opinions.”

Neither Rabbi Yehudah Alkalai nor Theodor Herzl lived to see the fulfillment of the dream of the Jewish homeland, but without both of these Jews and their roots in the Balkans, the dream of a Jewish homeland may have never been fulfilled.

- July 27, 2020

- Bosnia and Herzegovina , Serbia