Alexander the Great and His Women

History consists of a lot of times and places when it would have been the opposite of awesome to exist in the prescribed role for women. Certainly ancient Greece checks this box, as, in the worlds of a museum website, “Greek women had virtually no political rights of any kind and were controlled by men at nearly every stage of their lives.”

And yet, some women were able to move beyond this strict limitation – the best examples being the formidable women who were related to the wunderkind ruler of Macedonia and Greece, and unheralded ancient feminist, Alexander the Great.

Alexander himself needs no introduction. Not only did he conquer most of what was seen as the civilized world in the fourth century BC, but he did most of it before the age of 30. He put down his first rebellion, in the Balkan province of Thrace, when he was only 16. He and his father together conquered Greece, with only one real battle along the way.

And Alexander is still impacting the modern world – becoming a flashpoint in the ongoing argument between Greece and North Macedonia as to the actual ethnicity of the historical hero; extending to such actions as Greece forcing North Macedonia to label statues of Alexander the Great as a Greek hero in order to apply for accession into the European Union.

But Alexander didn’t exist in a vacuum. His father, Philip II of Macedonia (who, incidentally, was not considered Greek by Greeks at that time), was absent for most of Alexander’s childhood and Alexander’s mother Olympias had an outsized impact on shaping the future Emperor.

Olympias was described by Plutarch, writing more than 300 years after her death, as a jealous and sullen woman that men had reason to fear. Plutarch wasn’t known for his high opinion of women in general, though, so it stands to reason that the independent and strong-willed Olympias was not going to be exalted in his writings. To earn such a Plutarchian epithet, Olympias merely had to behave in the same manner as the men around her.

Born into the Molossian royal family in Epirus, Olympias’s 357 BC marriage to Philip II was a political one, although he reportedly fell in love with her. The marriage of the temperamental king and ambitious princess was a stormy one, not helped along by the tendency of nobles of that time to murder anyone who might be a future threat. Olympias’s ambition did not lend her to quietly accept a position as the fourth of what would be seven wives, either.

Two of Philip II’s six known children were from his marriage with Olympias: Alexander and a sister named Cleopatra. Alexander was given the finest education possible with other young Macedonian men, tutored by Aristotle. Cleopatra was not ignored, however. Not only was she schooled in the subjects that well-bred women were supposed to know, she was also taught “male” subjects such as science and government.

It seemed obvious to everyone that the children of Olympias were favored above all others. Alexander was even left to rule Macedonia as regent when he was only sixteen-years-old.

That is, until 337 BC when Philip II married the very-much-younger Cleopatra Eurydice, a native Macedonian noblewoman, and chaos broke out at their wedding. Cleopatra Eurydice’s uncle, the general Attalus, toasted the union and asked that they be blessed with a “legitimate heir”. Alexander rightfully took issue with basically being called a bastard for being only half-Macedonian, and not known for having a steady temper, attacked Attalus. Philip II sided with his general and Alexander stormed out of the wedding. Both Alexander and Olympias went into voluntary exile.

It turned out, however, that leaving Olympias’s daughter Cleopatra at the court created a weakness. In order to keep Olympias from turning her brother, King of Epirus, against Macedonia, Philip arranged a marriage between King Alexander of Epirus and Cleopatra of Macedonia. Nowhere amongst any reasons for opposing the marriage is listed the fact that Alexander of Epirus was Cleopatra’s uncle.

The marriage took place in 336 BC, but instead of being Philip’s moment of triumph over the machinations of Olympias it turned out to be his death. Philip was assassinated by his bodyguard, most likely in collusion with Olympias herself.

Alexander (soon to be “the Great”) was immediately proclaimed King and celebrated by killing a cousin, two other princes, and Cleopatra Eurydice’s father Attalus to secure his claim on the Macedonian throne.

Olympias had an agenda of her own to secure Alexander’s throne, and it involved killing Philip’s seventh wife Cleopatra Eurydice and her toddler daughter Europa. Both were tossed into a fire.

The burning of his step-mother and half-sister had not been a part of Alexander’s plans, and he was not happy with his mother for having it done. As unstinting with the execution sword as Alexander was for men, he wasn’t a fan of murdering women. In fact, during his later conquests he bragged in public about not forcing women to have sex (what we 2,300 years later would call rape, but which men of Alexander’s time considered normal procreation behavior).

Additionally, Alexander seemed to have good relationships with his siblings – although he was closest to his full sister Cleopatra. Another sister, Thessalonike, had also been fostered and raised by Olympias. Another sister, Cynane, had her husband killed in Alexander’s purge-for-power, but Alexander didn’t force any repercussions onto Cynane herself, or onto Cynane’s daughter Adea. Alexander certainly could have taken action against Cynane, who was even at that time known as a formidable force.

Writing 500 years later, the author Polyaenus mentioned Cynane in one of his military treatises:

“Cynane, the daughter of Philip II, was famous for her military knowledge: she conducted armies, and in the field charged at the head of them. In an engagement with the Illyrians, she with her own hand slew Caeria, their queen and with great slaughter defeated the Illyrian Army.”

Cynane was only half-Macedonian as well, as her mother was Illyrian, and she had been raised learning the art of war by her mother. Philip certainly knew what his daughter’s education entailed and didn’t interfere. Alexander also knew what his sister was capable of. Both Macedonian alpha-males seemed unbothered by the nontraditional niche Cynane inhabited. Further, before her husband was killed Cynane had given birth to a daughter named Adea. Alexander didn’t interfere when Adea was given the same upbringing Cynane received.

In 331 Alexander had already conquered huge swathes of the ancient world and was headed into Assyria and Babylonia. His sister Cleopatra’s husband-uncle was also at war in Italy, where he was killed in battle. Cleopatra, the mother of two children, had been named regent during his campaign, and no one batted an eyelash when she continued her regency after his death. Effectively, this woman of the ancient Greek world who was only in her mid-twenties was ruling one of the major powers of her time and no one was trying to unseat her. Certainly some of this was owed to the power of her brother, but the Molossians had a tradition of women assuming the role of head of household upon the death of the husband, and there was no reason why this would not extend to the ruler of the nation.

Macedonians were not as confident in the abilities of women, though, and during Alexander’s absence Olympias was causing a lot of headaches for the Macedonian regent Antipater, who complained about her incessantly to Alexander. Greek chroniclers were unimpressed with Olympias’s maneuverings, as historian Elizabeth Carney says, “…Greek expectations about women, who were supposed to be quiet, passive, stay of out public life, and maintain the family. Olympias did none of these things.” It is entirely likely that Olympias was the first women to participate actively in political life on the Greek peninsula, and the men of that time and place had no idea how to deal with her in the face of Alexander’s trust in feminine capabilities.

In 330 Alexander bowed to Antipater’s complaints, but instead of removing his mother from power all-together, he played a game of political musical chairs – moving Olympias to the regency in Epirus and his sister Cleopatra to the regency in Macedonia. Cleopatra, as Alexander’s sister and half-Macedonian herself, proved to be less antagonistic to the power structure in place.

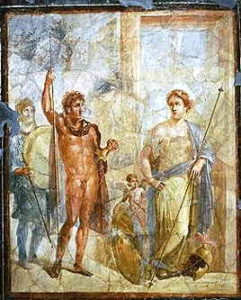

Polygamy was a prerogative of the Macedonian royal family, and Alexander took advantage of this making political alliances. He married daughters of royal families the areas he conquered, although that didn’t stop him from actually falling in love with and marrying the Bactrian Princess Roxana 327 BC.

“As for his marriage with Roxanna, whose youthfulness and beauty had charmed him at a drinking entertainment, where he first happened to see her taking part in a dance, it was indeed a love affair, yet it seemed at the same time to be conducive to the object he had in hand. For it gratified the conquered people to see him choose a wife from amongst themselves, “ wrote Plutarch.

It wasn’t until after Alexander’s death in 323 BC that Roxana’s ruthlessness came out. At this time she was most likely still a teenager. But she was the pregnant teenage daughter of a royal family who understood that the only way for her child to survive was to eliminate all rivals. With no delay, Roxana summoned and murdered Statiera and Parysatis, Alexander’s two other wives to keep them from declaring rival pregnancies.

At the time of Alexander’s death his mother Olympias was ruling as regent in Epirus, his sister Cleopatra was ruling as regent in Macedonia, his sister Cynane was leading armies and raising a daughter in the warrior tradition, and his wife Roxana was eliminating all rivals between her unborn child and the throne Alexander left behind. It was a legacy of feminine strength in the ancient world that would be unrivaled for thousands of years. It was not the end of the story, however.

Roxana would give birth to a son, named Alexander IV. Power struggles among his regents would create an awkward co-ruling situation with Alexander the Great’s brother Philip, who was mentally deficient. In to assert her own claim on the Macedonian throne, Cynane sought the opportunity to marry her 15-year-old daughter to Philip – creating another husband-uncle situation, albeit one that would most likely not be in the same vein as a marriage with a man in his full mental faculties.

Cynane’s martial prowess and her sibling relationship with Alexander the Great brought her the support of a great many soldiers in the Macedonian Army, and at Alexander’s death they marched with her to marry her daughter Adea Eurydice to Philip. Cynane was met along the way by Alcetus, whom she proceeded to berate loudly in front of everyone on the battlefield. When Alcetus could take no more, he struck Cynane down in front of both armies. True to her strong roots, Adea Eurydice managed to get the support of the Macedonian army, who forced the same Alcetus who killed Cynane to deliver Adea Eurydice to her planned marriage.

The death of Cynane had a rebound effect on her half-sister Cleopatra, who was now living in Sardis and acting as the civil governor of Lydia. Accused of being a part of the conspiracy to kill Cynane, Antipater had Cleopatra put under a gentle house arrest, and she would never be allowed to leave Sardis again.

It was in marriage that Adea Eurydice came into her own. In 321 BC, when she was seventeen years old, she demanded to be included in the regency. She was included. She worked well with Antipater, but age took its toll, and Antipater soon passed away. Left without many choices, Adea Eurydice then allied with another strong-arm claimant to the regency, Cassander, the son of Antipater.

At this point Olympias, who had tried to stay out of the whole regency mess, was called back to assure the throne for her grandson. At the head of an army, she rode to meet her son’s niece and her grandson’s aunt. The ensuing battle was referred to by the Greek historian Duris of Samos as “the first war between women.”

But Adea Eurydice’s army refused to fight the mother of Alexander the Great, and Adea was captured. She and her husband were confined in a small dungeon and neglected until Olympias had Adea sent a sword, a cup of hemlock, a rope, and a message to choose her death. Adea Eurydice chose the rope, and as she readied everything for her suicide she cursed Olympias to her last breath.

The rest of the strong women in Alexander’s life would all meet violent ends as well. Olympias would be captured by Cassander and stoned to death by the families of those she had killed. Her body would be denied burial. Cleopatra would attempt to escape Sardis to marry Ptolemy in Egypt, but was caught and murdered. Her funeral was said to be beautiful. And finally, Roxana, the wife who acted to remove all possible threat to her son’s rule immediately after Alexander the Great’s death, was poisoned along with Alexander IV in 309 BC.

The women of Alexander the Great’s family did not lead lives of leisure and pleasure. Instead they chose lives completely unknown by women in the Greek world; lives of more leadership, intrigue, and warfare than most men of their time. Although that choice led them to violent ends, it also created the template that would result in one of the most famous strong female rulers in history three hundred years later, when another Cleopatra would challenge the Roman world from her Ptolomaic home in Egypt.

- July 19, 2020

- Macedonia