Human Flesh is Too Salty

His Excellency, President for Life, Field Marshal Al Hadji Doctor Idi Amin Dada, VC, DSO, MC, CBE, Lord of All the Beasts of the Earth and Fishes of the Seas and Conqueror of the British Empire in Africa in General and Uganda in Particular

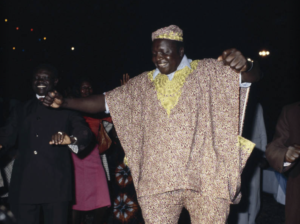

Few royal titles beat the one assumed by Uganda’s Idi Amin in sheer cheekiness. He had a frenetic energy that came out in his photos, and was as large in personality as he was in size (6’4″). He was the light heavyweight boxing champion of Uganda for several years, and played a mean game of rugby.

He also slaughtered, in an estimate by Amnesty International, 500,000 people during the eight years of his reign; including a tiny grandmother with leg ulcers who choked on a chicken bone during the hijacking of Air France flight 139. His nickname, “The Butcher of Uganda” was, if anything, an understatement.

There are multiple stories about how Idi Amin Dada got his name. In one, he took the name when he converted to Islam. In another, his father took the name upon conversion to Islam and Amin inherited it. In perhaps the most colorful account, given by his former cook Otonde Odera, the name “Dada” was added as a suffix to Amin’s given name because the word dada means sister in Swahili. When caught with one of his numerous lovers, Amin explained it away by saying, “She’s not my lover, she’s my dada.“

Whatever the origin of his name, Amin was born sometime around 1925, although there is no agreement about exactly when and where. His parents were not of the same ethnic group: his father was most likely of the Kakwa ethnic group and his mother, Assa Aatte, was Lugbara. Amin was raised by his mother in a largely rural environment while she worked as an herbalist to family members of the traditional Buganda royalty.

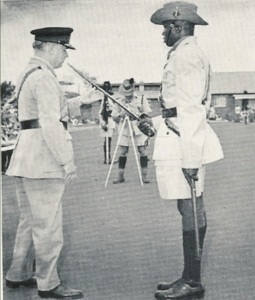

Sometime around the age of 21, in 1946, Amin joined the Kings African Rifles Regiment of the British Colonial Army. Initially an assistant cook, after receiving military training he was sent to Kenya in 1947. From 1949 and through the 1950s, Amin fought for the British Empire in the Shifta War and then against the Mau Mau. Along the way he was promoted through the ranks to Afande Class 2, the equivalent of a warrant officer and the highest rank native Africans could attain in the colonial army.

The highest rank available to Africans in the colonial army was no bar to Amin’s ambitions. On 15 July 1961 he was given a short-service commission as a lieutenant, one of only two Africans to become a commissioned officer.

Amin did not only fight Britain’s enemies, his prodigious energy and huge size placed him in nearly every competitive sport the army sponsored; holding the light heavyweight boxing championship from 1951 to 1960, swimming, and dominating on the rugby pitch. He did not, however, have a reputation for large amounts of brain power. As one British officer of that period said, “Idi Amin is a splendid type and a good player, but virtually bone from the neck up, and needs things explained in words of one letter.“

Uganda became independent from the United Kingdom on 9 October 1962, and at that time Amin was promoted to captain. His rise within the Ugandan military was equally as meteoric as it was within the British Colonial Army. By 1964 he was the Deputy Commander of the Army, one year later he was the Commander. Five years later, in 1970, Amin was the Commander of all Ugandan Armed Forces.

It was a quick rise, but it wasn’t without its hiccups. In 1965 both Idi Amin and the Prime Minister Milton Obote were implicated in a cabal that was smuggling arms to Zaire in exchange for gold and ivory. This, combined with the Buganda Crisis, presented an opportunity for Obote to consolidate his power. In a final sweep of consolidation and elimination of rivals, Obote promoted Amin to Colonel and Commander of the Army and had him lead an attack on the semi-autonomous Kingdom of Buganda’s palace – chasing the Kabaka (king) into British exile.

It was a violent, bloody, and brutal attack – something Amin was uniquely suited for, and Milton Obote was happy to have such a tool in his dictator belt.

Obote’s feelings toward Amin began to swerve as the 1960s wore on, however. In 1969 there was an assassination attempt on Obote. In 1970, wary of the army Amin was recruiting from his own ethnic group, Obote removed Amin from power and took control of the Ugandan Army himself.

Then Idi Amin heard that Obote planned to arrest him for misappropriate of army funds. It was the final straw.

What, and who, enabled Amin’s 1971 coup has been debated since it took place on 25 January 1971. Most British Ugandans at the time, and most people outside Uganda, believed that the British had played a large role in the shift of power, most likely to stop Obote’s nationalization efforts and stymie African objections to British arms sales to apartheid South Africa. Recently declassified reports show that if the British were involved, the British High Commissioner in Uganda, Richard Slater, had zero clue. Reports from Slater at the time emphasize the constant presence of the Israeli Defense Attache, Colonel Bar-Lev at Amin’s side.

Slater believed that someone would have to be helping Amin along, because Amin, “…had just enough intelligence to realize that he couldn’t run the country.” His reports back to London seemed to cast Colonel Bar-Lev as the brains behind the operation.

And, indeed, the first foreign state visit of Idi Amin was to Israel where the newly installed dictator met the normally unflappable Golda Meir, who was shocked at the shopping list for weapons Amin toted along.

Britain may not have been involved in Amin’s coup, but they certainly welcomed it and recognized the regime within a week. As The Times of London stated in an editorial, “The replacement of Dr. Obote by General Amin was received with ill-concealed relief in Whitehall.” The relief was initially appropriate, Amin quickly overturned Obote’s objections to the South African arms sales, breaking the united African front.

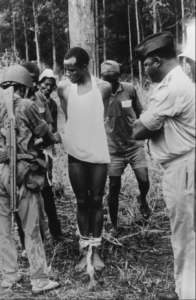

Amin’s seizure of power in Uganda was remarkably straightforward and greeted by cheering in the capital of Kampala. It wasn’t until after the coup that a hint of the bloody future was given when Amin moved to purge army rivals and soldiers from the Acholi and Lango tribes supporting Milton Obote. Within the year more than 5,000 soldiers had been murdered.

1971 had more to come, however. A week after seizing power, on 2 February, Idi Amin declared himself President of Uganda as well as Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces, Ugandan Army Chief of Staff, and Chief of the Air Staff. Parts of the constitution were suspended, military tribunals were placed above civil law, and Amin gave himself the ability to rule by decree. His replacement and restructuring of the state intelligence service into the new State Research Bureau (SRB) was also directed toward focusing not just power, but complete lack of consequences into Amin’s hands.

After his seizure of power in January, the second high point of 1971 for Amin when he arrived in London and scored a lunch with the Queen. When Her Majesty asked Amin what he had come to London for, Amin responded, “In Uganda, Your Majesty, it is very difficult to find a pair of size 14 shoes.“

But much like in Israel, Amin had quite a long shopping list for weaponry as well.

He rounded out the month of July 1971 with massacres of Lango and Ocholi tribe soldiers in the Jinja and Mbarara barracks. As the body count grew, burial space became more and more scarce. Amin’s band of killers began to dump the bodies of purged soldiers in the Nile.

1972 was scarcely less packed with events than 1971. It was the year in which Amin nationalized British businesses, expelled the Israelis, and began to receive the bulk of his weapons from the Soviet Union while East Germany became intimately intertwined in Amin’s State Research Bureau.

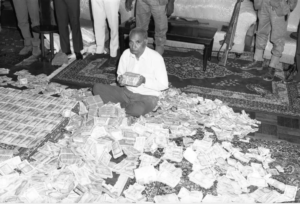

In August Amin decided to expel the Asians in Uganda. There were approximately 80,000 ethnic Indians in Uganda, 23,000 holding Ugandan citizenship, concentrated in the merchant and banking socio-economic groups. Indophobic laws had been introduced during the Obote regime as well, and the visibly outsider 1% of the population that had amassed 1/5 of Uganda’s economic power was an easy target.

At first only targeting non-citizens in Uganda, Amin briefly pronounced the expulsion of all Asians, regardless of citizenship, an act that was withdrawn within three days due to the large international outcry. Nevertheless, almost all of the Indian community chose to flee, with less than 4,000 known to have stayed in the country.

“The Asians only milked the cow, but they did not feed it to yield more milk. There are now Black faces in every shop and industry. All the big cars in Uganda are now driven by Africans, and not the former bloodsuckers. The rest of Africa can learn from us.” –Idi Amin

The extreme physical and sexual violence visited on the fleeing Indians only proved that their instinct to flee had been correct. To this day, 20,000 of the 80,000 strong community are still unaccounted for.

The community had an idea what was coming, though. In 1969/1970 30,000 members of the Kenyan community had been expelled from Uganda. The Indian community was forewarned about exactly what was coming.

Nearly immediately following the expulsion of Uganda’s Asian community, Amin was confronted with a badly organized attempt to overthrow his government by Ugandan exiles who had been living and training in Tanzania. On 17 September approximately 1,500 armed Obote followers crossed the border into Uganda.

The Obote fighters were not well trained, experiencing significant infighting, and didn’t have a tremendous amount of support. As a result, Amin was almost immediately able to gain the upper hand in the conflict and claimed complete victory on 19 September.

Amin was quick to throw out blame, not just on the Ugandan exiles and Tanzania’s Julius Nyerere for supporting them, but adding in Britain and Israel as enemies of his regime as well. More than 80 British citizens were taken into custody, women and children included.

His claims about British involvement were quickly refuted by the British themselves, but it was a few days before the British hostages began to be released. As they later reported, the conditions they were held in were horrific – and it was unquestionably by Amin’s explicit design.

A low-grade conflict with Tanzania would drag on for two months, until a peace deal to be overseen by Somalia was enacted.

In that time, Amin’s newest ally would cement his ties with the Ugandan regime. On 20 September, several Libyan planes landed in Khartoum’s airport, forced to land when the Sudanese government refused them permission to fly through Sudanese airspace. Onboard the aircraft were 20 Libyan officers and 377 enlisted men, who readily admitted that they were on their way to support Idi Amin’s government in the Uganda-Tanzania conflict. The Sudanese sharply refused permission for the Libyans to transit their airspace for that purpose, but agreed to let them return home.

The Libyan planes did not return to Libya, but instead headed to their original destination, unloading their weapons and soldiers in Entebbe as planned.

The Libyan support was a strong and obvious signal that Amin’s previous alliance with Israel, which had most likely been intimately involved with his path to power, as well as awarding him the Airborne Jump Wings that carried pride of place amongst his fruit salad of mainly self-awarded chest medals on his dictator uniform, would never be revived.

After cannibalism and rampant torture and murder, the Uganda of Idi Amin is perhaps most known for its role in the 27 June 1976 hijacking of Air France flight 139 and the Israeli Operation Thunderbolt to save Jewish hostages held at Entebbe Airport.

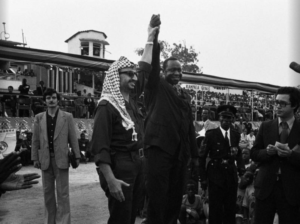

Amin had a strong friendship with Yasser Arafat, leader of the PLO and best man at Amin’s wedding to his fourth wife, so his support for the Popular Front For the Liberation of Palestine – External Operations was no surprise. Nor, given his rancorous break-up with his former Israeli allies, was his willingness to go along with singling out the Jewish hostages. However, the reality of the politics was not as simple. Recently declassified documents show that both Anwar Sadat of Egypt and Yasser Arafat attempted to negotiate for the release of the hostages, showing that to some extent Amin was acting out his own need for revenge.

The Israeli raid was launched from Kenya, the only country in the region who would extend their sympathies into action at the urging of the South African-born Brit Bruce McKenzie. Kenyan involvement nearly proved to be the undoing of the operation when Kenyan soldiers were overheard discussing the plans by the Ugandan ambassador to Lesotho. Stories conflict on whether this warning was passed onto Amin himself, but whether it did or not, he did not take preventative action.

Of the original 248 passengers, 148 non-Jewish hostages had been released and flown out by the time of the raid. One elderly woman, Dora Bloch, was being held in a Kampala hospital after choking on a chicken bone. This left the Air France crew and a few passengers who had refused to leave the Jewish hostages behind in the Entebbe Airport, a total of 106 men and women.

The Israeli commandos managed to rescue 102 of the hostages – with one being misidentified as a hijacker and killed by the commandos, one fatally wounded in the crossfire, and one shot by the hijackers. By the end of the short operation, all of the hijackers and one of the Israelis commandos, Lt Col Yonatan Netanyahu, had been killed.

In the aftermath of Operation Thunderbolt, Amin immediately ordered the death of Dora Bloch, whose body was finally discovered in 1979, buried on a sugar plantation. Bloch’s murder was accompanied by the murders of medical personnel who protested her fate and tried to protect her.

Amin executed 12 soldiers, accusing them of collaborating with the Israelis on the raid and ordered retaliatory killings of Kenyans in Uganda for Kenya’s support of the operation; 245 were killed, while 3000 managed to flee ahead of the death squads.

These events, particularly the disappearance and presumed murder of Dora Bloch, also led to the 28 July departure of Britain’s High Commissioner and the complete cutting of ties with the Ugandan Government.

Idi Amin’s final revenge after Operation Thunderbolt would occur on 24 May 1978, when Bruce McKenzie was leaving a meeting with Amin and a bomb on his aircraft ended the life of the man who had convinced Kenya to support the Entebbe raid.

The remainder of Amin’s reign was coming swiftly to an end, and he continued murdering and torturing until the end. People laughed with the dictator one day and were never seen again, and no one had any sense of what might bring about their torture or death.

In one incident recounted by Amin’s chef, the chief cook nearly lost his life when Amin’s oldest son consumed too much dessert.

Convinced his howling child had been poisoned, Amin went on a rampage in the kitchens, holding guns to the heads of the staff and threatening everyone with death. The chef loaded the child in his car and transported him to the doctor who, after an examination, managed to get the child to pass an enormous amount of wind.

With his trademark lighting-fast shifts of mood, Amin found the resolution of the near tragedy hilarious.

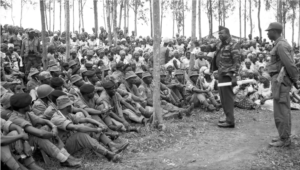

In 1977 a split in the Ugandan Army made itself clear. On one side were Amin’s, largely tribal, supporters. On the other were those who supported the Vice President General Mustafa Adrisi, who wanted to purge foreigners (like Amin’s Sudanese) from the military.

Amin purged Adrisi while the latter was in the hospital recovering from a car accident, but the removal caused intense political unrest.

A mutiny of troops in November 1978 was put down by Amin’s forces, but the perpetrators escaped across the border into Tanzania. Ever resentful of the support Nyerere had given to Ugandan exiles, Amin took the opportunity to invade the neighboring country once again. His armies looted property, killed civilians, and declared the annexation of the Kagera area of Tanzania.

Nyerere could not let Amin’s aggression stand, and this time he was far better prepared than in 1972. Mobilizing Tanzanian troops and Ugandan exiles, Nyerere launched his own invasion. Although Amin’s steadfast Libyan ally sent 2,500 troops and Arafat sent about 200 guerrilla fighters, the Tanzanians and exiles took Entebbe Airport in April 1979. More than 600 Libyans were killed in the fighting, along with about 1,000 of Idi Amin’s Ugandans and approximately 2,000 civilians.

On 11 April Idi Amin fled by helicopter into exile; first in Libya, and then to spend the rest of his life in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia with a generous pension that was predicated on his remaining apart from politics. He mostly did refrain from dabbling in politics, at least anywhere other than Uganda, where he continued to fund an opposition that remained fanatically devoted for several years.

Amin, who would often eat up to 40 oranges a day while in exile because they “vitalized his libido”, was placed on life-support on 18 July 2003, and pronounced dead on 16 August. He left behind between 46 and 54 children, six wives (of whom at least two were dead, one of which he tortured and dismembered), more than 500,000 murders, torture chambers, and accusations of cannibalism he responded to with the statement, “It’s not for me. I tried human flesh, and it is too salty for my taste.”

His mercurial moods were legendary, and had those around him in constant terror. “There is freedom of speech,” Amin said, “but I cannot guarantee freedom after speech.” In Amin’s Uganda, that was more likely to mean death by torture than imprisonment. And the bodies from his reign are still being unearthed today.

- January 8, 2021

- Uganda