The King Who Returned

When King Cetshwayo died on 8 February 1884, the circumstances were suspicious. Officially his death was due to a heart attack, but not even the British representatives who observed his autopsy could agree on whether or not the last independent king of the Zulu had been poisoned.

Cetshwayo’s life was remarkable in many ways. His rise to power among the Zulu was never assured; as the least-favored son he was never expected to rule. And yet, he killed his favored brother at the Battle of Ndondakusaka in 1856 and seized power. He slaughtered his brother’s supporters, but then allowed his father to remain as a figurehead until the man’s death.

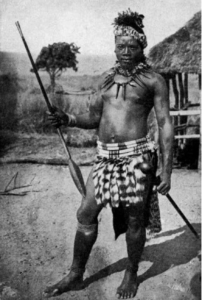

Although Cetshwayo did not shy away from battle and violence, and proved himself to be an able commander on the battlefield, he also utilized diplomacy to an extent never before commanded by Zulu rulers. The kings before him tended to depend almost entirely on the matchless superiority of the Zulu war machine.

Cetshwayo’s chosen path was to keep Zulu culture and the Zulu people separate and autonomous within the boundaries of Zululand rather than constantly warring with the British on his borders or mixing indiscriminately with traders and missionaries. In doing so, he was quick to jump on any challenge by outsiders to his kingdom – in one case taking the South African High Commissioner to task for the man’s protest at Zulu death sentences for girls who refused marriage.

“Why does the Governor of Natal speak to me about my laws? Do I go to Natal and dictate to him about his laws?”

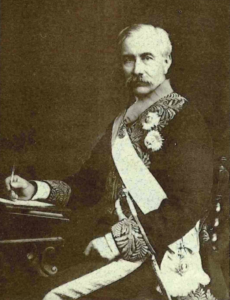

It was with the aggressive pushing of a view of Cetshwayo as a bloodthirsty savage that the British High Commissioner of South Africa, Sir Henry Bartle Frere, managed to push the two nations into the Ango-Zulu War in 1879; a war that Cetshwayo could not win.

Indeed, the war ended when Cetshwayo was captured by the British who removed him to Cape Town and held him captive in 1879.

But unlike most other defeated Kings under colonial systems, Cetshwayo’s capture did not solidify his historical reputation as a blood-thirsty barbarian who was rightfully removed from power so that a civilizing influence could be brought to bear on the defeated people.

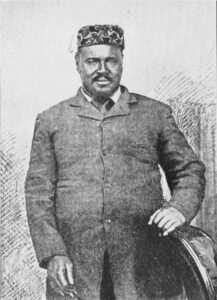

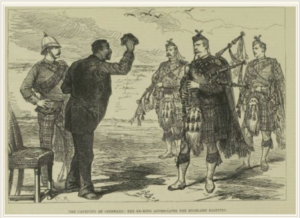

For one thing, Cetshwayo did not behave as a humiliated King. Rather than assume a mantle of subservient humility or constant lashing rage, Cetshwayo’s approach was to win his captors over. He dressed neatly in the Western style, with small touches of Zulu culture that were enticingly exotic to the British. He spoke politely and respectfully while only responding to those who treated him with reciprocal respect, saying, “I love the English… I am the child of Queen Victoria. But I am also a king in my own country and I must be treated as such.“. His enormous 6’8” frame radiated a jovial nature that was responsible for him being granted more and more privileges until he was finally given permission to travel to London to plead for the return of his kingdom with Queen Victoria herself.

He arrived in London on 3 August 1882 and immediately attained celebrity status. Far from being salaciously painted as a bloodthirsty savage, the British press described him as “every inch a King“.

Cetshwayo’s public opinion campaign worked. Much to the chagrin of the authorities in Durban, Queen Victoria reinstated Cetshwayo as the Zulu King in 1883, although his lands were diminished. Cetshwayo returned to a Zulu Kingdom in the midst of infighting, and before the year was over he was attacked in his capital Ulundu by his rival Zibhebhu and wounded in the thigh.

Retreating to eShowe, Cetshwayo was dead within six months

Cetshwayo was a pleasant person with a good presence, handsome, concerned for all his people, and extremely kind in his speech… when cases sere brought before him of quarrels among his subjects. He tried them justly, and in the majority of his cases reconciled the disputants, not wanting them to quarrel, and brought them together by directing that each should produce a goat to be slaughtered and each should come to the same homestead and eat it together. — Magema Fuze in Abantu Abamnama, the first book written by a Zulu in Zulu for a Zulu audience

Although it is Shaka who has gathered most of the representation in history books, it is the last independent Zulu ruler Cetshwayo who exhibited the traits of war leadership, diplomacy, and even-handed rule. And it was Cetshwayo who managed within his lifetime to turn his image from a bloodthirsty savage to a noble and dignified ruler whose dignified presence provoked difficult questions about the British colonial rule in South Africa.

To read more about Cetshwayo, please click here.

For more South African history, please click here.

- February 8, 2021

- History , Interesting