Misdirections and Grossly Unreasonable

I think submission to authority and absolving oneself from blame by saying that one has to obey orders are widespread… I think all medical students should be taught about the research on submissiveness being a key etiological factor in the perpetuation of atrocities. They should be fully familiar with Milgram’s work and reflect on Hannah Arendt’s concept of the ‘banality of evil’.–Frances Ames before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

Frances Ames’s life was a series of “shouldn’t have been able to” moments. Raised in utter poverty, her father had deserted the family when she was young, Ames spent time in a Catholic orphanage when her mother was unable to care for her. She survived typhoid fever. She managed to lift herself from poverty and obtain an education, eventually becoming the first woman to earn a medical degree from the University of Cape Town. Eventually she became the head of neurology at Groote Schuur Hospital.

When her husband died suddenly and quite young, Ames was left the single parent to four children. Her Xhosa maid was instrumental in the family’s survival, and Ames would record her life in the 2002 book Mothering in an Apartheid Society.

Perhaps it was the series of life events that Ames had to overcome which led to her dogged pursuit of justice for the victims of the apartheid regime in South Africa and the doctors who collaborated with the police.

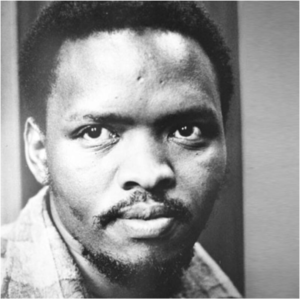

When activist Steve Biko died in custody in 1977, South Africa and the world watched the ensuing inquest and was appalled at the vast gulf of difference between the findings of the inquest committee and the evidence. Horrified by the complicity of medical doctors in Biko’s death, medical doctors in South Africa met to challenge the findings of the inquest, resulting first in a submitted complaint to the South African Medical and Dental Council (SAMDC). Ames was at the forefront of the doctors protesting the findings of the inquest.

As the fight moved up an ever steeper hill, with first the SAMDC and then the Medical Association of South Africa (MASA) refusing to find any fault in the findings of the official doctors that Biko showed, “…no evidence of abnormality or pathology on the detainee” despite obvious photographs and statements to the contrary, the doctors pushing for justice began to drop off one-by-one.

For many who retreated from the fight against the apartheid regime and its entrenched supporters it was a question of safety. As Dr. Ames continued to push in her quest, she was physically threatened. Her superiors at work moved to remove her from her teaching and medical positions, and she was routinely called a “whistleblower” in a derisive manner.

But Ames and five other doctors continued pushing for justice, and finally a case regarding the Biko malpractice reached South Africa’s Supreme Court. The Supreme Court decision resulted in the SAMDC being forced to open a new investigation, taking all evidence into account. The new investigation found blame on behalf of the doctors, who were given slaps on the wrists as punishment. Ames would speak derisively of Doctors Lang and Tucker for the rest of her life.

Nor was Ames finished when she managed to bring the truth of Steve Biko’s death to light. She continued to counsel political prisoners, drawing attention especially to those who were held incommunicado in solitary confinement.

Ames was at the forefront of exposing the government’s complicity in the death of another anti-apartheid activist as well. Siphiwo Mthimkhulu was released from custody on 20 October 1981. He had been captured at the end of May in a shoot-out and wounded in the arm. While held he had been subjected to torture that included electrocution, beatings, water boarding, and lack of food

But none of these accounted for Mthimkhulu’s symptoms after release; the pain in his extremities, vomiting, and extreme stomach distress. When these symptoms drove Mthimkhulu to the hospital on 28 October, Dr. Ames ran tests and found a large amount of Thallium in Mthimkhulu’s system.

He had been poisoned, although the government denied it.

But Ames’s tests were enough for Mthimkhulu, who brought a suit against the apartheid government for torture and spoke openly about being poisoned.

The suit was never completed. On 14 April 1982 Mthimkhulu disappeared. Later, in testimony to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, several policemen testified that Mthimkhulu and his friend had been lured to an abandoned police station where they were drugged, shot, and hastily burned to ashes the day of their disappearance. Their ashes were scattered in the Fish River. Mthimkhulu, armed with his medical tests conducted by Dr. Ames, had proved to be too big a problem for the apartheid government to allow to continue.

Ames herself would testify in front of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in 1997, where she pointed out that, despite the notoriety of the case in the public mind, Biko was not the first detainee to die in the custody of the apartheid government, but the 46th.

Bishop Desmond Tutu would later refer to her by saying, “One of the handful of doctors who stood up to the apartheid regime and brought to book those doctors who had colluded with human rights abuse.“

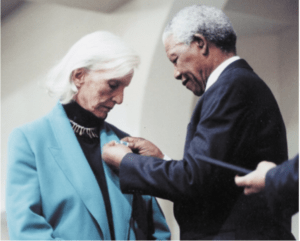

Ames was also recognized for her work by Nelson Mandela, receiving the Order of the Star of South Africa, the highest civilian award in the country, for her work on behalf of political prisoners.

Although Ames’s work on the Biko case was her most publicized, she was also extremely active in the movement to decriminalize marijuana. Beginning her studies in 1958, she was most impressed by the drug’s ability to improve the quality of life for those suffering from multiple sclerosis.

When Ames died of leukemia in 2002, she was cremated and her ashes scattered with hemp seeds behind her hospital, devoted to her ideals to the end.

**the South African Supreme Court found in the Variava decision that, “[earlier resolutions were based on] misdirections and were grossly unreasonable…“

For more on the history of South Africa, please click here.