The Twisted Road to Independence

Independence is not an easy thing to establish, especially not in the Balkans. Serbia’s moves toward independence from the Ottoman Empire started in 1804, and de facto independence was achieved by 1830. Full independence did not happen until 1878, however.

Bulgaria’s path to independence was even more convoluted, with moments of Schrodinger’s Independence in 1878 when Bulgarians gained independence with one treaty and lost it with the next.

The twisted road to independence began in earnest in 1870, when the Ottoman Empire finally granted the Bulgarian Church, which had been under the Greek Patriarchate since 1393, its own exarchate. This was a change that Bulgarians had been struggling toward for hundreds of years, and the Ottoman hope that it would calm an increasingly restive population proved to be entirely in vain. Rather, the Bulgarian Orthodox Church was a focal point which allowed Bulgarian nationalist sentiment to rise.

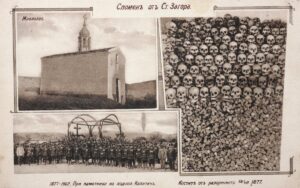

An early uprising in 1875 was quickly put down by the Ottomans, but more was to come. On 20 April 1876 the Bulgarian Uprising began. The Ottoman Empire, far into its decline as “the Sick Man of Europe” and having seen its European territory steadily eroding, reacted with swift and complete violence. The Ottoman irregular soldiers, the Bashi-Bazouks, were sent in and atrocities throughout the Bulgarian areas of the uprising multiplied with such rapidity and barbarity that the world responded with horrified outrage. In one area over 18,000 victims were recorded, with evidentiary photographs of piles of skulls and bones as proof.

“The number of children killed in these massacres is something enormous. They were often spitted on bayonets, and we have several stories from eyewitnesses who saw the little babes carried about on the streets… on the points of bayonets.” JA MacGahon, in a 22 August 1876 letter to the London Daily News.

The uprising was put down by May 1876, and lasted less than a month. The Ottomans targeted movement leaders with horrific violence. “Then I heard Ahmet-Aga command with his own mouth for Tendafil to be impaled and burnt. The words he used were ‘shishak aor’, which is Turkish for ‘to put on a skewer’.” said Tendafil’s daughter-in-law Bosilka to a British journalist. “At the time this was happening, Ahmet-Aga’s son took my child from my back and cut him to pieces, there in front of me.“

The world erupted in outrage, which the Ottomans largely ignored. This was to prove a vast miscalculation on their part, and not too far in the future.

The Russian Empire, although it had not been victorious in the Crimean War, was watching the Ottoman Empire closely for revenge. They observed that the promise the Ottomans had made in the 1856 Treaty of Paris, to grant Christians fully equal rights to Muslims in Ottoman areas, had not been fully enforced. In fact, there were increasing abuses of Christians in primarily Christian areas of the Empire, as the Ottomans attempted to keep control over their crumbling possessions.

Russia noted this fact, and when word of the Ottoman atrocities during the Bulgarian April Uprising reached the Russian public, support for their Slavic Bulgarian brothers attained complete and far reaching support across all Russian social classes. When further Ottoman cruelties from the failed Serbian attempt for full independence, the Russian Empire felt justified in springing into action. At the end of April 1877 the Russo-Turkish War began. By the beginning of March 1878, the Ottomans were soundly and completely defeated.

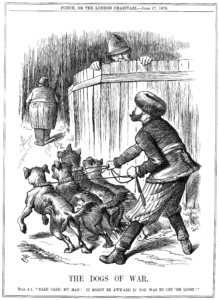

Turkey was well aware from the beginning that they would be unable to stand against the Russian military, and in the very beginning they turned to their ally Great Britain and requested help. For all that the two had been allies during Crimea, the Ottoman atrocities in Bulgaria and Serbia had caused a change-of-heart in Great Britain. Reports of babies impaled upon bayonets while the Bazi-Bazouks celebrated in obliterated villages had ensured that the Sick Man of Europe would get no medicine of support.

The Treaty of San Stefano was signed on 3 March 1878, a day still celebrated as Liberation Day in Bulgaria, because it granted Bulgaria back all the lands that the Ottomans had occupied since the fourteenth century. It also granted Bulgaria a disputed area of land known as Eastern Rumelia and most of Macedonia, including direct access to the Mediterranean Sea. Large gains were also granted to Montenegro (which doubled its size), Serbia, Romania, and Bosnia and Herzegovina was to be recognized as an autonomous province.

Knowing that this would most likely set off a firestorm in the rest of Europe, Russia covered its bases by referring to the treaty as a “preliminary treaty of peace.”

It was indeed too much for the Great Powers to bear. As much as they disliked the Ottoman Muslim rule of what they perceived should be a Christian Europe, it was far less difficult to deal with than an ascendent Russia which was inspiring nascent greater Slav-dom movements in Eastern Europe. Nor did the Great Powers want to see Russia with access to the Mediterranean for its warships.

The Great Powers sprang into action and called for the Congress of Berlin, which was held in June/July 1878. Great Britain, Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, Italy, and Russia were all to take part in the Congress, chaired by Otto von Bismarck. The Ottoman Empire, as the losing side of the most recent war, was to observe the proceedings but was not allowed to participate.

Bulgaria, whose independence was the catalyst for the Congress of Berlin in the first place, was not only kept from participation, but was not allowed at the conference at all. Surprisingly, since it had been Russia fighting for the benefit of Bulgaria and the rest of the Balkans, it was by Russian insistence that the Bulgarians were excluded. They were not yet, fully, an independent nation according to Russia’s reasoning, and therefore not entitled to participate in mapping out their own future.

The Treaty of Berlin kept much of the structure of the Treaty of San Stefano. The independence of Serbia, Montenegro, and Romania were enshrined. The threat of a “Greater Bulgaria” allied to Russia was just too great a risk for the Great Powers to take, however, and their brief independence was revoked. In retrospect, Russia’s insistence that Bulgaria not be allowed to participate was probably a good indication that this was the likely outcome from the beginning. Bulgaria was reduced to a Principality that was still nominally under the Ottoman Empire. Macedonia was ripped away and returned to the Ottomans full rule, as was Kosovo. Bosnia and Herzegovina was not returned, but neither was it allowed to merge with Serbia; instead the Austro-Hungarian Empire would occupy the vilayet.

Although no one could see the future of the early 20th Century from 1878, and the role the divisions of the Treaty of Berlin would play in starting the First World War, foreign and uninvolved analysts of 1878 still saw it as a terrible idea.

“Austria, with a folly that has characterized her diplomacy for many years past, refused the offer of Russia to occupy Bosnia and Herzegovina two years ago on the ground that it would be a moral crime and political blunder to do so. She has since perpetrated the crime and committed the blunder and placed herself politically in a position which must, sooner or later, lead to her complete disintegration,” the North American Review, November-December 1878. “In a word, when Austria signed the Berlin Treaty, she became a party to what, in all probability, will prove her own death warrant.“

Foreign analysts also pointed out that, although the Ottomans could sign anything, their ability to actually enforce the terms on their population was somewhat less-than-likely.

The treaty did allow for a ruler in Bulgaria, and the dashing young Alexander of Battenberg was chosen. Although the new Knjaz Alexander started with a conservative agenda, he soon began to implement reforms. On 20 September 1885, Alexander issued a manifesto that Eastern Rumelia had been reunited with Bulgaria – seven years after the Treaty of Berlin had separated the two. This act, as well as Bulgaria’s asylum to several members of the Serbian opposition, triggered the Russo-Bulgarian War – which Bulgaria promptly won. Unification with Eastern Rumelia was basically forced upon the world, which resulted in an enraged Russia withdrawing all their people from Bulgaria. As counter-intuitive as that might seem from the outside, the Russians wanted a compliant Bulgarian Prince who would allow Russian aspirations to continue without interfering. It became clear that Alexander was not that sort of prince.

One year after unification, a cadre of pro-Russian military officers ejected Alexander from Bulgaria and he signed his abdication. The fact that he remained popular among many Bulgarians was illustrated in 1893, however, when he was interred in an elaborate and easily recognizable tomb in Sofia upon his death.

The search was on for a new, more compliant, prince in Bulgaria, and on 7 July 1887 Ferdinand of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha was elected to the role. Europe’s nobles rolled their eyes and thought him too effeminate, weak, and fun-loving to make much of a dent during his tenure, but Ferdinand turned out to be quite surprising. Liberal reforms in Bulgaria, including the Tarnovo Constitution, continued under Prime Minister Stefan Stambolov for seven years, during which Bulgaria’s relations with Russia continued to be fragmented. Stambolov believed that Russia, far from being altruistic, was a ploy to turn Bulgaria into a Russia protectorate. That ended on 31 May 1894, when Stambolov was assassinated. The fun-loving, effimate playboy Ferdinand had set in motion a coup to return Bulgaria to the pan-Slavic fold, and he cemented the return by converting his infant son Boris to the Orthodox Church. The conversion outraged Ferdinand’s staunchly Catholic family, including the Emperor of Austria-Hungary, Franz Josef.

Ferdinand continued to bide his time, and in 1908 saw the Young Turks rebellion in the Ottoman as an opportunity. On (old calender) 22 September 1908, at the Holy Forty Martyrs Church in Turnovo, Ferdinand I declared Bulgaria’s independence from the Ottoman Empire. Almost simultaneously Austria-Hungary annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina and Crete joined itself with Greece. There was just too much at once, and by spring of 1909 Bulgaria’s independence was recognized by the world.

And it really did end up being that easy in the end. The Ottomans, fully occupied internally, did not demand compensation for Bulgaria. Russia generously cancelled the Ottoman war debt. Bulgaria agreed to transfer their tribute payments to Russia. The Bulgarians took control of the internal railway.

To celebrate nationhood, in 1912 Bulgaria joined four other Balkan nations in pushing the Ottomans out of Europe for good.

- September 14, 2020

- Bulgaria