A Holiday For an Abandoned Revolution

On 22 July 1994, a group of junior officers in the Gambian National Army, led by Yahya Jammeh, staged a disorganized and badly planned coup and somehow managed to end up in control of the nation of the Gambia. That is how the longest lasting democracy in West Africa came to an end; and even after Jammeh himself was ousted more than twenty years later, the holiday, no longer a holiday, remains.

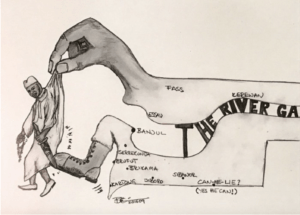

The Gambia is tiny West African nation almost completely surrounded by Senegal. It was a part of Mansa Masa’s Mali Empire. Then it was a part of the Songhai Empire. The area of the Gambia was mentioned by the explorer Ibn Battuta in 1352, “[The inhabitants] possess some admirable qualities. They are seldom unjust and have a greater abhorrence of injustice than any other people. There is complete security in their country. Neither traveler nor inhabitant in it has anything to fear from robbers or men of violence.”

Europeans arrived at the River Gambia in 1455, and for several years the Portuguese controlled the area’s connections to Europe, before they were briefly in the hands of the Polish and Lithuanians, before they passed to Britain. The Gambia would remain a British colony of varying degrees until 1965, when power passed to a Gambian government led by Prime Minister Sir Dawda Jarawa. At first a constitutional monarchy, in 1970 the Gambia became a republic within the Commonwealth.

Jarawa tried. He, unlike other African leaders, did not personally enrich himself through his position. But he was unable to stop the sticky fingers of other officials. Corruption was endemic on the African continent, and in 1981 a coup by the Marxist Gambia Socialist Revolutionary Party was attempted while Jarawa was attending the wedding of Prince Charles and Lady Diana in London.

With the help of troops from Senegal, Jarawa was able to take back the country – although not without a body count estimated between 500 – 800 people and a significant backlash from Gambians concerned about how much power Senegal was wielding within their nation.

To try and combat these issues Jarawa created a new Gambian Army and launched an economic recovery program. On one level the economic program was a success – the budget deficit was reduced, the foreign exchange reserved rose, and the debt service arrears were eliminated. But the financial upturn created more possibilities for corruption, and there was no shortage of Gambians willing to take advantage of the new opportunities. It was nothing short of humiliating.

By 1992 the Gambia was undeniably one of the poorest nations in the world: there was only a 75% literacy rate and 75% of the population was living in absolute poverty. But in addition to this, there was now a Gambian Army that was growing increasingly restive.

In 1994, fed up with months without pay and the disparity between Nigerian senior officers and Gambian junior officers, the junior officers struck. And to the shock of everyone, they were successful. Although the United States transported Jawara to Senegal on one of their warships, the rest of the world declined to further intervene.

Yahya Jammeh and his co-conspirators had bungled their way into controlling a country. The date would be honored from that moment on.

In the days after the coup, Jammeh’s group gave public speeches addressing complaints that many Gambians also had about the previous government. The Gambia had been delegitimized by a lack of accountability, corruption, and ineffectiveness. They promised to fix these issues, and to dedicate themselves to the protection of human rights.

At the same time they made these promises, they also suspended the 1970 constitution, banned opposition political parties, and put the press under strict regulations with threat of violent reprisal.

It was enough to make a population’s head spin, and although the government of the United States and the European Union suspended aid shipments in response, Jammeh mustered support against them by claiming they were acting as “neocolonialists.”

The Gambia, once the nation with the most freedoms, whose previous government had not resorted to political disappearances or detention of opposition leaders on fabricated charges, was no longer even pretending to value human rights.

Gambian journalists were imprisoned and exiled. The death penalty was re-established and used most frequently on political opponents. To create a veneer of legitimacy, Jammeh held a ceremony of retirement from the military (really a political rally) and then went on to win the 1996 elections. It might have been more difficult if he hadn’t introduced a new constitution that made opposition political parties nearly illegal.

Jammeh continued on with political disappearances and hounding the press. To gain more support in the populace, he undertook vast infrastructure projects and endowed schools and universities. Many people benefitted from these ventures, and many looked the other way as disappearances mounted. Many people looked the other way as Jammeh kept up a campaign of murder and intimidation against the press. People in this conservative, majority-Muslim nation also weren’t terribly bothered by Jammeh’s increasingly strident anti-homosexual rhetoric. “If you do it [engage in gay sex], I will slit your throat – if you are a man and want to marry another man in this country and we catch you, no one will ever set eyes on you again and no white person can do anything about it.” Many of them agreed that homosexuality was wrong in principal, even if they felt that Jammeh was being a bit too aggressive in discussing it.

And besides, wasn’t it Yahya Jammeh who banned female genital mutilation in 2015, ordering strict penalties to protect the young women of the Gambia? And in 2016, didn’t he create even more strict penalties to end the problem of child marriage?

Of course, people also believed Jammeh in 2007 when he said that he had created an herbal paste that could cure AIDS and HIV. The politics of the situation just weren’t simple, many Gambians thought.

Part of the problem with acknowledging the crimes being committed in the government’s name was the lack of openness among victims. There were severe repercussions from anyone caught admitting to being mistreated. A child whose father may have been imprisoned or killed by Jammeh’s government could under no circumstances admit it, or that child would lose even more family members. Jammeh’s personal death squad, the Jungulars, operated with impunity, assassinating those who were against the regime and regularly setting upon and murdering migrants to the tiny nation. Disappearances, indefinite detention without charges, and extrajudicial murders touched every family – but no one was allowed to talk about it.

In one of the more odd totalitarian moments of Jammeh’s rule, hundreds of Gambians were arrested and forced to ingest hallucinogenic drugs under charges of witchcraft. His auntie had died, and Jammeh was sure that the witches responsible were amongst those dragged into his cells.

Jammeh’s government might have even continued on if it weren’t for Facebook. His absolute control of the press within the Gambia had kept the citizens in the dark about how widespread the violence and repression of his government had been. The introduction of 3G, wifi, and smart phones brought the torture and murders to the forefront. In April 2016 the opposition leader Solo Soldang was arrested and tortured to death. When other opposition leaders gathered to demand his body for burial, they were beaten and arrested as well. But this time, instead of being ignored by the government-controlled media, Facebook and WhatsApp groups run by the Gambian diaspora began to pick up and circulate the stories. People began to react.

Sukhai Dahaba, a former schoolmistress, began to go daily to protest in front of the National Intelligence Agency headquarters. She would hold up a calama, a type of wooden spoon, and demand an accounting of the missing. Soon she was joined by hundreds of women, most of them over the age of fifty. The women protested daily, and eventually the government gave up trying to keep them away.

Jammeh, and ethnic Jolo, was also caught several times making inflammatory statements about the Gambia’s largest ethnic group, the Mandinkas. It was a well-known prejudice of his, dating back at least to the early 1980s. “[Jammeh] has always singled out Mandinkas as bad people,” said fellow gendarmerie officer Binneh S Minteh.

To his utter shock, the events added up and Jammeh lost the December 1, 2016 election. Gambians wanted a change.

But Jammeh didn’t want to give them that change. Although he initially accepted the election’s outcome, he quickly changed his mind and nullified the results. By 17 January the entire ECOWAS region was involved, backed by the United Nations and Jammeh fought back by declaring a state of emergency, which prohibited “acts of disobedience” and “acts to disturb public order.” It gave him the power to do whatever he wished without consequences.

That was the last straw. As 46,000 people fled the country, Senegal massed troops at the border and demanded Jammeh leave by midnight on 18 January. The deadline passed, and on 19 January Senegalese troops entered the Gambia. On 21 January Yahya Jammeh stepped down and left the country for Equitorial Guinea, where he reportedly lives comfortably in a mansion.

The reign of His Excellency Sheikh Professor Alhaji Yahya AJJ Jammeh Babili Mansa was ended.

The Gambia has set up a Truth and Reconciliation Commission, much of whose testimony is televised. Watchers are frequently reduced to tears as they hear stories that sound so much like the evils many of them also lived through. Jammeh’s theft of millions of dollars from the Gambian government has been documented, and his accounts in the Gambia and the United States have been frozen while the details are worked out. He was also accused of multiple incidences of rape.

Although the new president, Adama Barrow, has publicly stated that Truth and Reconciliation Commission does not exist to prosecute Yahya Jammeh for his crimes, but merely to investigate possible crimes, on 12 January 2020 the Gambian government released a statement saying that Yahya Jammeh should not return to the Gambia without permission, as his safety could not be guaranteed.

The anger against the Jammeh government has not abated. But Revolution Day is still celebrated.

- July 19, 2020

- Gambia