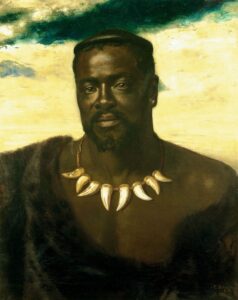

The Last Independent Zulu King

Cetshwayo’s name is not as well known as that of his uncle Shaka. Shaka had managed to turn the small Zulu tribe into the powerful Zulu nation before being assassinated by his brothers. Cetshwayo, who officially ruled from 1873 to 1879, was confronted with the might of the British Empire and history records him as the last independent ruler of the Zulus.

Cetshwayo was not supposed to inherit the Zulu kingdom. His father, Mpande, favored a younger son named Mbuyazi because Mbuyazi was the son of one of Shaka’s widows. King Mpande, not considered a strong ruler by anyone’s standards except his own, considered Mbuyazi’s parentage to give him a higher social status than that of Cetshwayo. This higher status, in Mpande’s estimation, jumped the line of succession.

Cetshwayo did not agree. Nor did a good many of his Zulu nation, as he and a large following were able to confront Mbuyazi in 1856 at the Battle of Ndondakusuka. Cetshwayo had the larger number of warriors, but Mbuyazi convinced the white settler John Dunn to support him. Mbuyazi also burned a line in the grass, demanding his warriors not retreat beyond the line near the swollen Tugela River – no matter how badly the battle went.

And for Mbuyazi, the battle went very badly. After an initial attack by Cetshwayo was repulsed, his second attack and superior numbers overwhelmed his brother. Mbuyazi and another five brothers were all killed, while many of his warriors were swept away by the roiling river. Mbuyazi’s white allies escaped on a boat, which they were careful to keep any Zulu from boarding.

Cetshwayo did not stop with his victory, he put 20,000 of Mbuyazi’s supporters to death – not sparing women or children. Those children – born and unborn, he reasoned, could grow up to become a challenge to Cetshwayo’s throne.

Cetshwayo’s father was despondent to hear about the loss of his favorite son and refused to recognize Cetshwayo. It didn’t matter, though. Although Mpande was allowed to remain the ruler-in-name-only and handle ceremonial matters; everyone, white and black, knew that Cetshwayo was now the actual power behind the throne. At times he felt the need to remind his father and the Zulu nation who the actual power was – such as when he ordered the death of his father’s favorite wife Nomantshali and all her children. Nomantshali herself and two of her daughters were hacked to death. One of her sons was murdered at the feet of King Mpande himself.

The message was received.

In 1873 King Mpande died, although the exact date was kept a secret to ensure a seamless succession. In addition to the traditional Zulu ceremonies, to which Cetshwayo demanded a national return, a new ceremony was added: Cetshwayo was crowned in the European fashion by the British representative Sir Theophilus Shepstone.

In his final traditional act of ascension to the throne, Cetshwayo established his capital and called it Ulundi (the High Place).

His participation in Cetshwayo’s coronation notwithstanding, Shepstone was still not comfortable with his leadership. Cetshwayo’s strong leadership and command of the Zulu nation, his emphasis on a return to the leadership style of Shaka, and the possibility of border raids made him a threat not only in the short term, but a threat to the ability of the British colony in South Africa to form a confederation similar to that in Canada.

“Cetshwayo is the secret hope of every petty independent chief hundreds of miles from him to feels a desire that his color shall prevail, and it will not be until this hope is destroyed that they will make up their minds to submit to the rule of civilization.” Sir Theophilus Shepstone, 1877

With the Zulu power in mind, Shepstone and the British High Commissioner Sir Henry Bartle Frere began to formulate a plan that, at its heart, was a heavy-handed attempt to provoke the Zulu kingdom into a reaction that would make a war to reduce Zulu power inevitable.

Cetshwayo was well aware of the game that was being played, but recognized that the superior numbers and firepower of the British Empire would eventually overpower the Zulus if given the chance. He was determined not to give British colonial leadership the excuse they were looking for while simultaneously keeping his prestige at levels that would not undermine his rule of the Zulu Kingdom as a whole. It was a difficult dance, and Cetshwayo’s reply to a message taking issue with the behavior of the Zulu within their own borders showed how well he was balancing the entire situation: he and Frere were equals, and since Cetshwayo was not complaining about the way that Frere was conducting his power within his own borders, Frere should stop trying to tell Cetshwayo how to rule Zululand.

Henry Bartle Frere did not, of course, stop agitating. Finally, on 11 December 1879, he had accumulated enough minor and trumped up charges to issue Cetshwayo with a humiliating ultimatum. Cetshwayo refused the British demands, and Bartle Frere had his excuse for the invasion he had already conveniently planned.

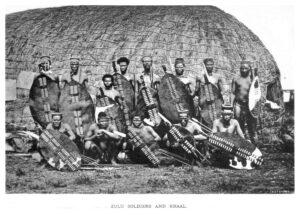

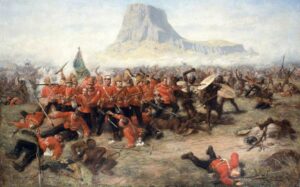

The first British invasion of Zululand was a disaster. Despite superior supplies and firepower, the British were victims of their superiority complex and their first engagement with Zulu troops on 22 January 1879 at the Battle of Isandlwana ended with 1300 of 1800 British troops dead.

An overnight engagement at Rorke’s Drift, cemented in the world’s consciousness by the Michael Caine movie from 1964, was a hard-won British victory with extensive Zulu casualties, didn’t do much to save the campaign, and the British troops withdrew to await reinforcements for a second invasion.

Cetshwayo knew that the British defeat was going to cause him future problems, and that it would only harden British opinion agains the Zulu. Further, he had expressly forbidden his forces from crossing the Zululand boundary, an order ignored by his brother, Prince Dabulamanzi kaMpande.

British forces withdrew, but everyone, Cetshwayo included, knew they would return.

There were other battles and skirmishes between the British and the Zulu, but it was on 29 March 1879 that the tide of the Anglo-Zulu War turned. At the Battle of Kambula the British managed to extract a victory from which the Zulu were never able to recover when 20,000 Zulu met 2000 British and were soundly defeated with large casualties. The British were no longer taking the Zulu capabilities for granted, and this new humility was accompanied by a determination to finish the problem once and for all.

The Battle of Kambula may have been the turning point in the war, but it did not end the war. Skirmishes and smaller battles continued for several months, including a small skirmish that resulted in the death of the Imperial Prince Napoleon Eugene of France. Despite every effort to ensure the prince’s safety, the unexpected appearance of forty Zulu warriors during a scouting run ended with the Prince’s body showing 18 assegai wounds, one of which entered his brain through his eye.

The death of the Imperial Prince shocked Europe profoundly, and it seemed to shock the Zulu as well, who immediately sent word that they would never have killed Napoleon Eugene if they had only known who he was. In fact, Cetshwayo included the return of the prince’s sword amongst the peace gestures he was continually making to the British command.

But the British now knew they had the upper hand, and they were not going to stop until the power of the Zulu kingdom was demolished. On 4 July 1879, the two armies met at the Battle of Ulundi – the final battle of the Anglo-Zulu War.

The Zulu were decimated, and the humiliated Cetshwayo fled. The British knew that he was the only Zulu left who could possibly reconstitute the kingdom, and they concentrated on finding him, which they did on 28 August. The Zulu kingdom was no more – it was broken into several small chieftainships, one of which was held by the white John Dunn.

Cetshwayo was first held in Cape Town, and then transferred to London. Once he was no longer a military threat, depictions of Cetshwayo in the British press no longer emphasized his barbarian tendencies. Rather, they depicted him as inherently regal, masculine, and good humored. Cetshwayo was aware of this, and played his role to the hilt. He wanted the British to return him to his kingdom, and felt this was the best way to ensure it.

Cetshwayo was right. The infighting amongst the various Zulu factions proved to be a thorn in the side of the colonial British. The former King was a far better option, and arrangements were made for his return in 1883.

It was a return that didn’t last long.

The Zulu kingdom was too fractured, and even the well known and respected Cetshwayo could not bring it back together. When Cetshwayo and his followers were attacked, they fled. And on 8 February 1884, Cetshwayo died.

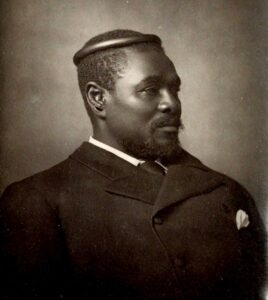

Eighty years later, when the movie Zulu was filmed in South Africa during the height of apartheid, the role of Cetshwayo was played by his great-grandson. Mangosuthu Buthelezi did not stop at portraying his ancestor on film, however. He was one of the leaders of the fight against apartheid and would go on to found the Inkatha Freedom Party. Leadership, it seems, runs in the family.

- August 16, 2020

- South Africa