Decided in Secret

In the secret meeting on Brioni in the wee hours of November 2 and 3 1956, Marshal Tito of Yugoslavia informed the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev that members of the Nagy government in Hungary had approached the Yugoslav Ambassador, Dalibor Soldatić, and requested the possibility of asylum. Tito informed Khrushchev that Yugoslavia would be granting that request. According to all accounts, Khrushchev dismissed the information with a wave. As anyone who follows politics knows, if you didn’t explicitly say no, you must have meant yes.

And so when the Nagy government and their families took asylum in the Embassy of Yugoslavia at 5:30 in the morning on 4 November as the Soviet tanks rolled in, the Yugoslavs believed they were acting in line with what had been agreed at Brioni and the Soviets felt fully betrayed.

Almost immediately the fragile relationship between the two began to break apart. On 4 November Khrushchev fired off a telegram demanding Nagy be turned over, “… as far as the further sojourn of Nagy and his group in the embassy, excesses could occur with them, not only by the reaction but also by the revolutionary elements. Thus bearing in mind the Hungarian Revolutionary Worker-Peasant government does not have security organs at present, it would be expedient to deliver Nagy and his group to our troops for transport to the Revolutionary Worker-Peasant government in Szolznok.“

Given the threatening tone of the message, and the earlier request from the Yugoslav government that their embassy be protected by the Soviets, it’s hard to believe that when Soviet tanks fired on the embassy on 5 November, killing the Cultural Attache Milenko Milovanov, it was not deliberate. The Yugoslav Foreign Minister Koča Popović immediately accused the Soviets of acting deliberately, but it was dismissed as an accident (and later billed to the Hungarian government by the Yugoslavs).

But Soviet anger at the Yugoslavs was not appeased. On 7 November Khrushchev fired off another letter to Tito, which Tito would refer to as “vulgar”. “Now that Nagy and his cohorts have found refuge in the Yugoslav Embassy, our assessment of the causes of the developments in Hungary would require a revision. The fact would certainly introduce suspicion into our relations and would inflict an irreparable damage upon them.“

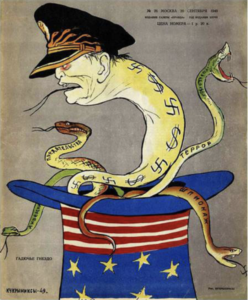

Khrushchev was leaving no doubts – Yugoslavia had always been an issue for its stubborn independence from the Soviet socialist bloc, and the actions of the Yugoslav government were just proving that Yugoslav agitation was behind the uprising in Hungary.

This new explanation for events was released to the general public in the 8 November issue of Pravda, in an article entitled Fifteen Years of the Albanian Workers Party written by Albanian dictator Enver Hoxha. The article was a direct attack on Yugoslavia and Tito’s style of leadership, referring to it as a “cult of personality.”

Tito, who had led the Yugoslav Partizan movement during World War II, one of the only countries able to drive out the Nazis without depending entirely on the Red Army to do the defeating for them, had made a success of his earlier split from Stalin in 1948 and wasn’t cowed by Soviet threats. The propaganda against “Titoism” was old news by 1956. He responded by giving a speech in Pula, Croatia on 11 November which, although conceding that the second Soviet invasion was necessary as the lesser of two evils to keep Hungary within the socialist fold, he also pointed out that Soviet blindness to the hate toward their chosen Hungarian leader Rakosi put the blame for the uprising directly on the Soviets. Tito also put forward again his idea of a “third way” in which groups would come to socialism “in accordance with the specific conditions of her country.“

Moscow was livid. But in truth, Tito was walking a fine line. While Nagy was in the Yugoslav Embassy, he was neutralized. The Hungarian Revolution (which was uncomfortably inspiring certain nationalist groups within the multi-national Yugoslavia) was ending. The Western world was celebrating Tito for “protecting” Nagy from the Soviet Union. And Tito was handed an opportunity to prove his independence from the Soviet Union and show them that, despite better relations, he was not going to submit Yugoslavia to becoming just another satellite under the Soviet thumb. The problem was that there seemed to be no way to end the stalemate.

Which is why, on 18 November, the Soviet Presidium took matters into their own hands and decided that anything necessary to bring Nagy into the Soviet fold would be acceptable. There would be a kidnapping, but in order to effect the kidnapping it would have to remain secret – and negotiations for Nagy’s release would have to continue as though they were being done in good faith.

For our ongoing series about the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, please click here.

- November 18, 2020

- History