The Contrary Communist

For Croats I was a Serb and a unitarian from the beginning. To Serbs, a Frankist [radical Croatian nationalist] and Ustaša; to Ustaše a dangerous Marxist and communist; to Marxists a salon communist; to clergy and believers, the antichrist who should be nailed to a shameful pillar. For the bourgeoisie after the war I am to be blamed that it happened and to the communists [I am blamed because] I did not join the Partizans. For soldiers I am a pacifist and to pacifists I am a Bolshevik. — Miroslav Krleža

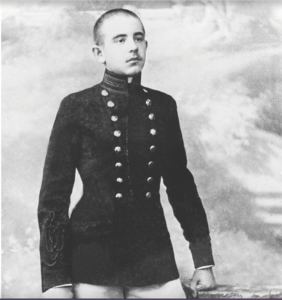

When Miroslav Krleža was born in Zagreb in 1893, it was still a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The man who would become one of the most significant Croatian authors of the 20th Century and one of the most singularly contrary figures in socialist Yugoslavia started his education by attending a military academy in Budapest. When World War I broke out he defected to Serbia, where he was dismissed as a spy and sent back to the Austro-Hungarian border. His military re-entry into the Austro-Hungarian army after his failed desertion earned him a demotion and assignment to the Eastern Front.

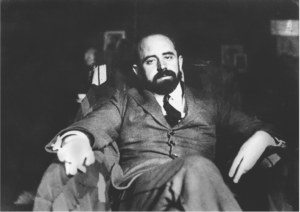

It was after the war when Krleža joined the Communist Party and established himself as a prolific modernist writer. Eventually his works would include everything from short stories and novels to memoirs to poetry, and plays as well. Although Krleža was a staunch communist, between 1918 and 1939 he was involved in an increasingly strident disagreement with the Soviet-led communist movement and it centered on his writing. The conflict began in 1929 with the publishing of Stanko Tomašić’s “Tragikomedija Slobodnog Pera”, which examined the conflict between literary idealism and economic realities. This literary work was the first shot fired in what would become a worldwide argument amongst communist artists.

Communist movements throughout the world were creating works of art in the Socialist Realist school. These works became so ubiquitous throughout the socialist world, that they are immediately recognizable to most people. But while the Socialist Realist school was exploding in communist popularity, Krleža argued that artists should not be constrained by ideology. Meanwhile, the argument opposing Krleža boiled down, in effect, to “there is no such thing as apolitical art.” (Ivana Perica)

As the editor of numerous left-leaning publications, Krleža’s opinions on the appropriate expressing of socialist art had a wide audience. The discussion, increasingly strident through the 1930s, created a crisis within the intelligentsia of the Balkan left that came to be known as “The Conflict of the Literary Left.” It moved away from the discussion of Socialist Realism and became a free-for-all of incriminating accusations about how much freedom artists should have and how much control ideology should have over the production of art.

As Savić Marković Štedimlija said, “There is one thing we are perfectly aware of: we perceive literature exclusively as a means in a struggle.” Štedimlija’s contribution to the Conflict on the Literary Left is an interesting addition, as Štedimlija’s initial sympathy to the Communist Party was jettisoned completely to work with the Croatian Ustaša.

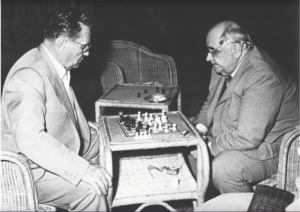

The discussion grew so rancorous that Stalin sent an emissary to mediate the issue – a Croatian/Slovenian named Josip Broz. Krleža’s subsequent acquaintance with Broz would prove to be an enduring, and lifesaving, friendship.

In the minority, Krleža opposed any controls over art. That opinion, and his vocal opposition to the Great Purge of the 1930s, led him into conflict with the rising tide of Stalinism. Finally, in 1939, he was ejected from the Communist Party, most likely for writing Dijalekticki Antibarbarus, which mocked orthodox Stalinism. His writings had already influenced a generation of youth in the Balkans, however, who would spend the years of the coming second world war dreaming about a southern Slav homeland united under socialism.

When the Ustaša came to power in Croatia in 1941, Krleža was arrested along with other known leftists. He was not a part of the jail-break that left one of his good friends, August Cesarec, murdered. Instead, he spent the war in silence. He did not write or publish. He did not join the Partizans, nor did he in any way associate with the Ustaša. Several reasons for his withdrawal have been given for this over the years: that Krleža feared acts of revenge by his former communist colleagues over his vocal denunciations of Stalinism, or that he feared for his Serbian wife and did not want to bring attention to her and have her sent to Jasenovac. Whatever the reason or reasons, Krleža waited out the war in Zagreb under a modified form of house arrest.

After the war, in the victorious Yugoslavia of Marshal Tito, leaders were expected to have served bravely as Partizans. Krleža spent the first few years of Yugoslavia in an internal exile, although it was not a complete exile. His earlier works were still published and although he was technically internally exiled, he was still appointed Vice-President of the Yugoslav Academy of Arts and Sciences in Zagreb.

When Tito and Stalin split, Krleža was soon rehabilitated and allowed to the top of Yugoslav authors. In 1950 he founded the Yugoslav Institute for Lexicography, and was the head of the institution until his death in 1981. He continued to release high profile works, and was the head of the Yugoslav Writer’s Union from 1958 to 1961. He was often with Tito, who considered him a close and trusted friend, which is probably what protected Krleža from the post-war purge of non-Partizans.

Ever the contrary communist, Krleža signed the Declaration on the Name and Status of the Croatian Literary Language, which was released on 13 March 1967 and led to the Croatian Spring. The document, which broke with the united Yugoslav ideal by proclaiming Serbian and Croatian languages were the same linguistically but had separate standards and their own national language names. Tito’s Yugoslavia was based on the idea of a common southern Slav culture, and so the Croatian Spring was seen as a restoration of Croatian nationalism and not to be tolerated. The movement was brutally suppressed by police, and it marked the last public political and social position taken by Krleža until his death in 1981.

Whether human folly is the work of God or not, it does not diminish in practice. Centuries often elapse before one human folly gives place to another, but like the light of an extinguished star, folly has never failed to reach its destination. — Miroslav Krleža

To read more about Yugoslavia’s history, please click here.

- March 15, 2021

- Yugoslavia