The Often Hidden History of the San

The San people of Southern Africa first really came to the world’s attention in the 1950s with a miniseries and a book by Laurens van der Post titled The Lost World of the Kalahari. Of course, Africans weren’t unknown in the world – not only had the trans-Atlantic slave trade forcefully and violently moved people from the African continent around the world, but in a stomach churning act directly refuting the complete prohibition of slavery in the western world, a man named Samuel Phillips Verner purchased pygmies for exhibition in 1904. The purchased humans included a man named Ota Benga, who was eventually exhibited next to the monkeys in the Bronx Zoo.

The world was not unfamiliar with people from Africa, but they did have a tendency to lump the diverse nations and tribes all together. It was in the 1950s, with the book and miniseries by Laurens, that the San people became known as a separate and distinct group on the African continent by the average person in the West.

Although this was the first real appearance of the San in popular culture, they had been the subject of in-depth studies since the mid-1800s. The German philologist Wilhelm Bleek studied their language and culture, and his work was carried on after his death by his daughter Dorothea. Dorothea’s aggregation of the San language was published after her death in A Bushman’s Dictionary, which was so all-encompassing it is still referenced today.

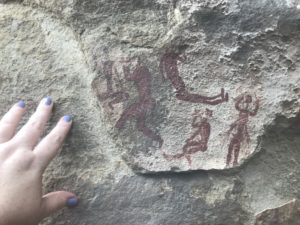

Dorothea Bleek spent twenty years, between 1910 and 1930, collecting linguistic and anthropological information on the San, and cataloging rock art in South Africa, Botswana, Namibia, Angola, and Tanzania. Many of the sites, thousands of years old, have since become severely degraded, so Bleek’s work was essential in categorizing and copying the historical artworks for future generations.

The San people themselves were undergoing an era of enormous change in the twentieth century. Among the oldest cultures on earth, DNA studies have shown that they are descended from the first populations of Botswana and South Africa. They are most well known for inhabiting the Kalahari, and although evidence shows they have always lived there, they were more spread through the region prior to the Bantu invasion, when stronger and more agriculture-focused tribes migrated south and pushed them into smaller areas of land. That loss of land not only continued to be a problem, but intensified as between the 1950s and 1990s they were forced out of their semi-nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle in places like the Central Kalahari Game Reserve and into government-mandated farming programs.

As their lifestyle was forced to change, many traditional beliefs and practices were lost. In South Africa, for instance, the San language spoken in the South is not even included among the country’s official languages. They have lost oral traditions, ceremonial traditions, and even a unique method of clapping that can be observed on old reel footage, but is no longer practiced – nor is there even a memory of this method of clapping.

And the changes continue to come, none for the better. In Botswana, where the largest concentration of San are concentrated, they have been forcibly evicted from their traditional home in what is now the Central Kalahari Game Reserve. They have repeatedly brought suit against the Botswana government for denying them access to ancestral areas, but the government has, for the most part, refused to abide by any court decisions in favor of the San people.

The changes in San culture have been profound. Removed from a lifestyle in which they were self-sufficient, they were not ready to take up a stationary agricultural existence. Although given livestock, they didn’t have a deep understanding of how to care for crops and animals, and diseases and death ran rampant. The tools they were used to using, nearly identical to a set of 42,000-year-old tools discovered at Border Cave in KwaZulu Natal in 2012, were not suited to a stationary lifestyle nor suited to animal and plant husbandry in the 21st century. San family groups, which had tended to be small, were forced into larger villages in more desolate areas without their traditional resources. This broke down the family and societal structure in place for tens-of-thousands of years, which was more egalitarian and relied on consensus decisions. Consensus decisions take time, though, and subsistence agriculture requires far more intensive work than that of the hunter-gatherer who is intimately aware of the cycles of their environment. That time is just not available, decisions must be delegated to chiefs and councils who can more easily take advantage of the population without the consensus requirement.

Now the San rely on government grants to meet their needs, and alcoholism is rampant. Separated from the ceremonies and initiations of the past, many of them are lost. In South Africa, where land claims to return areas to their original inhabitants is a hot-button issue, the numerous claims filed by the San to regain land seized by the Bantu tribes have mostly been ignored.

It is a sad fate for the culture whose members created the oldest known artwork in the world 73,000 years ago in the Blombos Cave.

Even the extant artwork from the past is rapidly disappearing. Although projects like are digitizing and making the rock art available for people to view anywhere in the world, changing environments, urbanization, and graffiti are working together to erase signs of human habitation that range from tens-of-thousands of years old to century-old depictions of the arrival of European colonists. Few of these sites have any form of protection, and without dedicated and rigorous public campaigns to urge veneration of precious connections to the historic past of Africa, they may be lost for good.

Lost, possibly, along with the San people themselves, who until now have managed to survive longer than any other human culture in the world.

- July 26, 2020

- Botswana , Namibia , South Africa , Tanzania