The Patron Saint of Croatian Poets

My Dear Heart: Do not be too sorrowful and upset on account of this letter. God’s will be done. Tomorrow at ten they will cut off my head and your brother’s, too. Today we pardoned each other with all our heart. Therefor I ponder this letter and ask you for everlasting forgiveness. If I have mistreated you in some way, or offended you, as well I know, forgive me. In the name of Our Father I am quite prepared to die and am not afraid. I hope that the Almighty God who has humiliated me in this world will have mercy on me. I would pray to him and ask him to whom tomorrow I hope to come that we may meet each other in everlasting glory before the Lord. I know nothing else to write to you about, neither our son nor the rest of the our poor possessions. I have left this to God’s will. Do not be sorry, everything had to be so. In Wiener Neustadt, the day before the last day of my life, at 7:00 in the evening, April 29, 1671. May Almighty God bless you and our daughter Aurora Veronika. — Petar Zrinski’s farewell letter to his wife

Not all rebellions succeed, no matter how justified those fighting think they may be. When the Austrian Empire signed the 1664 Treaty of Vasvar with the Ottoman Empire, the terms were terrible for the Hungarian and Croatian nobles who had been fighting on the war’s front lines. Although the Austrian troops were successfully beating the Ottomans back, the need for a quick end so that the army could be repositioned to respond to a French threat gave the Sultan the advantage in treaty terms. Not only was the (losing) Sultan to be given a yearly tribute, but the lands that had been regained in fighting were to be ceded back to the Ottoman Empire. And to add insult to injury, some of the land being returned had never belonged to the Ottomans in the first place.

Austria had, in modern parlance, “done Croatia and Hungary dirty.” The resentment bred by the Peace of Vasvar would not lay silent, a rebellion was brewing – and it would be led by Croatian Bans Nikola and Petar Zrinski, Fran Krsto Frankopan, and the Hungarian Francis Rakoczy.

Petar Zrinski had made a brilliant marriage in 1641 to the beautiful Ana Katarina of the Frankopan family. They were two of the last families left in the small part of Croatia not occupied by the Ottoman Empire, a situation that had been described by Pope Leo X as, “Remnants of the remnants of the once great and celebrated Kingdom of Croatia.” In addition to the warfare skills required of nobles living on the Croatian Military Frontier, the family were also avid consumers and writers of literature and poetry.

Unusually well educated for a women of her time, Katarina wrote and published a book of prayers in 1660, called Putni Tovaruš. She spoke German, Croatian, Hungarian, Latin, and Italian fluently. She also passed a need for learning to her children; her son Ivan spoke seven languages.

It is often difficult to accurately describe the contribution of women from the past to historic events, and Katarina is no exception to this. However, there are definite clues that show her support for the brewing rebellion against the Austrian Empire was more than just nodding and smiling as her husband spoke about his plans.

Very early on in the planning of the Zrinski-Frankopan Rebellion, Ban Nikola Zrinski died after wrestling with a boar during a hunt. Petar took over just a few months after planning began, along with his brother-in-law Fran Krsto Frankopan (also a voluminous author of the time). The conspirators, knowing that they could not face the Austrian Army on their own, began casting around for support amongst countries not allied with the Empire.

Sweden, France, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, and the Republic were all approached and all refused to join in or finance the rebellion. In desperation, the leaders approached the Ottoman Empire, whose favorable treaty had caused the Croatian and Hungarian nobles to rise up in the first place.

The Sultan, not ready to risk his treaty-guaranteed good deal and head right back into fighting, duly reported to the Austrian Emperor that the Croatians and Hungarians were planning a bit of nefarious disturbance.

The Sultan wasn’t passing on information the Austrian Emperor didn’t already have – several others had reported the goings-on in his territories, but the conspiracy seemed more like venting than actions that were likely to go anywhere. Several plots were planned, but never carried out. Katarina was sent to discuss support with Louis XIV of France, a direct example of her assistance in the anti-Austria cause.

When a plea for support to the Pasha of Buda failed, Zrinski and Frankopan turned themselves into the Austrian authorities and asked for mercy. Emperor Leopold I was well aware of the powder keg waiting to explode in Hungary, and so the two were pardoned as an attempt to curry favor.

It didn’t work. In 1670 conspirators began circulating pamphlets calling for violence against the Emperor, a Protestant uprising in Hungary, and inviting the Ottoman Empire to invade.

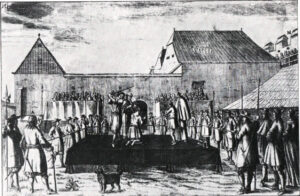

Leopold I acted swiftly: he sent a letter to Petar Zrinski and Fran Krsto Frankopan promising them a pardon if they would come to Austria and again beg forgiveness in light of the most recent rebellious events. But Leopold did not hold to his word. The two were arrested as soon as they arrived in Vienna in March 1671, swiftly tried, and executed in Wiener Neustadt on 30 April.

He committed the greatest sins than the others in aspiring to obtain the same station as His Majesty, that is, to be an independent Croatian ruler and therefor he deserves to be drowned not with a crown, but with a bloody sword. — sentence of Petar Zrinski in the Austrian court

Then the might of the Austrian Empire came down on Croatia and Hungary. Another 2000 nobles were arrested to prove a point. Protestant churches were burned, shut down, and there were forced conversions to Catholicism. Forty-one Protestant pastors were executed for fomenting rebellion. Hungary’s nominal self-government was abruptly ended, and Croatia would not have another Croatian Ban for more than sixty years.

The family estates of the Zrinski and Frankopan families were confiscated and the families themselves sent into exile. The only leading conspirator not sentenced to execution was Francis I Rakoczi, whose mother Sophia Bathory successfully pleaded for his life.

Katarina Zrinski was held under arms, and then told to seclude herself in a convent for the rest of her life. She only survived her husband by two years, dying after being stricken by mental illness. She left behind a legacy of patronage in the arts and literature, as well as composed poetry. She left behind, as well, a legacy of independence carried on in her oldest daughter Jelena. Jelena was married to the reprieved Francis I Rakoczy, and she was the mother of the leader of the next uprising as well.

The Zrinski and Frankopan families were largely forgotten in Croatian history until 26 July 1861 when the Croatian politician Ante Starčević made a speech about them in the Croatian Parliament. From that moment on, interest in the families, and especially in Katarina Zrinski, was revived. She became a symbol of Croatian patriotism, art, and literature; and the renewed interest allowed the Brotherhood of the Croatian Dragon to bring the remains of Zrinski and Frankopan back for burial in Zagreb Cathedral. Societies of Croatians throughout the world, named after Katarina.

For more information about Croatian history, please click here.