To Arrest the Leader

“We are fully in accord with your reply to our ambassador that Nagy and the others hidden in the Yugoslav Embassy should in no way be transferred to Yugoslavia, since they were the organizers of the counter-revolutionary demonstration, and you cannot allow two Hungarian governments to exist – one in Hungary and the other in Yugoslavia,” Andrei Gromyko, soon-to-be Foreign Minister of the Soviet Union to Janos Kadar.

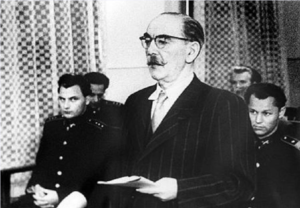

On 17 November 1956 the Soviet Presidium decided to kidnap Imre Nagy and had instructed Janos Kadar to proceed in such a way as to keep from raising suspicions. On 22 November their chance came. Operating under a safe conduct signed by Janos Kadar himself, it became immediately obvious as the remnants of the Nagy government boarded the provided bus that everything the Yugoslavs had negotiated for on their behalf had been a lie. Confronted with a Russian driver on their Hungarian bus, which was soon boarded by more Soviet officers and surrounded by Soviet vehicles, the Yugoslav representatives reacted with horror and intent. Dalibor Soldatić, Yugoslavia’s ambassador to Hungary, realized that the Soviets present could not speak Hungarian and in the local language informed Nagy that he could stay at the embassy. Although no record has been released that enumerates Nagy’s reaction, he did not leave the bus and return to asylum. Instead, two of the Yugoslav diplomats boarded the bus with the Hungarians to assure the safety of the Nagy government, only to be kicked off unceremoniously less than a block after pulling away from the embassy.

Within 24 hours the last of the Nagy government was imprisoned, out-of-reach of the rest of the world, in Romania.

Marshal Tito, the charismatic leader of Yugoslavia, immediately penned a letter of protest to the Soviets that left no illusions as to how Yugoslavia was interpreting the Soviet actions and the consequences to be expected.

The Yugoslav government was well away, Tito said, that Nagy and his cohorts were fully committed to remaining in Hungary and were being held against their will. Soviet actions were a violation of every international law and failure to adhere to the agreement negotiated by the Yugoslavs “…will damage Yugoslav-Soviet relations.“

Tito’s words were not idle threats – the Yugoslav-Soviet relations had only just begun to repair from the Tito-Stalin split. Tito had made the most of his time out of the Soviet orbit to outline a “third way” to socialism, based on national needs. It was this “third way” that underpinned the Hungarian Revolution itself, and was a very real threat to Soviet dominance of the Communist movement.

In addition, Tito’s ability to bridge between the Communist East and the Capitalist West was proven and legendary. His threats were not idle foot-stomping.

But the Soviets were in no mood to listen. Nagy and his family were being held on Lake Snagov, separate from the other members of the government.

On 25 November Janos Kadar released his own statement – that Imre Nagy was being held in Romania “for his own safety.” Later, Kadar would state that the Yugoslavs had been verbally complicit in Nagy’s abduction, a charge the Yugoslavs immediately and strongly protested. In retrospect, although Tito’s prodigious talents at RealPolitik allow for the possibility of such a convoluted timeline of events – the fact of the deterioration in Yugoslav-Soviet relations and relations with Hungary seem to exhibit a very real sense of anger and betrayal. Nor can it be overlooked that Kadar’s “admission” of Yugoslav complicity came during a time when he was struggling against a rising tide of pro-Yugoslav sentiment in Hungary and needed to make the neighboring independent socialist government look complicit to discredit them.

Imre Nagy would return to Budapest in June 1958 – in time for a show trial and his execution by hanging. His last words were, “I do not appeal to the court for clemency.“

Nagy never resigned as leader of the Hungarian government.

For our ongoing series about the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, click here.

- November 23, 2020

- History