What is Heresy?

Empires have to begin and end somewhere, and in Europe the Balkans are the beginning and ending of East and West, and North and South. Within the Balkans, it is Bosnia where everything comes crashing together. As Saint Sava said in the thirteenth century, “…we are doomed by fate to be the East in the West and the West in the East!” It is no surprise that such a crossroads of civilizations would often roil with the currents of the tides of history, and develop unique marriages of cultures.

It is also no surprise that the unique coping mechanisms that enabled the people in such a crossroads to effectively function within the breaking waves and blowing winds of cultural clash would be acceptable to exactly none of the cultures whose extended influence was causing such upheaval.

This is, summarized, the history of the Bosnian Catholic Church.

In more modern times the Bosnian Catholic Church became conflated with the historical and heretical sect of Christianity called the Bogomils. As little written evidence remained from either group and both ended up being destroyed in Crusades and Catholic fervor, the coalescence of the two in popular thought was nearly inevitable four hundred years after both churches disappeared. More recent scholarly research has turned up far more evidence, however, which shows that the two were distinctly different- although the vast majority of the evidence that still exists is through Catholic sources gathered during persecutions.

From the appearance of the Slavs in the mid-sixth century, the Roman influences in what had been the Province of Illyria began to recede. Formerly Christian areas reverted to the pagan religion of the Slavs until another wave of conversions, spurred on by the development of a uniquely Bosnian alphabet, came through and converted the people of the Balkans again. By the eleventh century the region was being tossed back and forth between the Orthodox Eastern Christianity of the ruling Byzantines and the Western Christianity of the Catholic Hungarian Empire. Ruling nations switched back and forth between the two with enough regularity to give the Bosnian people spiritual whiplash. It wasn’t until the reign of Ban Kulin, from 1180 to 1204, that the Catholic Church consolidated its hold on this mountainous, forested, and fiercely independent part of its empire.

By this time the Bosnian Catholic Church had already begun to exhibit its unique characteristics, brought about the constant exposure to both churches and the difficulty of bringing educated religious professionals into the hinterlands of Bosnia, as well as the propensity of Bosnian villagers to be more concerned with the practical aspects and practices of religion rather than its doctrine. The most likely explanation for three centuries of misunderstandings, aside from a primal need of neighboring nations to accumulate land and power, was that although the Bosnian Catholic Church was rooted in Catholicism, it was a fusion of the Eastern and Western churches whose illiterate peasants clung to the remnants of pagan rituals and magic spells which were repackaged to fit with the beliefs of the Roman Catholic Church. And, most importantly, the Bosnian Catholic Church liturgy was most likely done in a Slavonic Language and not Latin.

The Catholic Church first turned its eyes to possible heresy in Bosnia under Ban Kulin, who was forced into signing the Bilino Polje Abjuration in 1203. Set off by the Serbian prince Vukan Nemanjić, who sent a letter to the Pope disingenuously stating that he, “can’t tell Bosnian Christians from the heretics,” and also mentioned that Ban Kulin had been welcoming the heretics expelled from other areas into his banate. Although this should have resulted in Vukan Nemanjić forever carrying the epitaph of “Tattletale and Whiny Backstabber”, what it did instead is provide documented proof of the beginning of what would soon become the Bosnian Church.

Despite the fact that the inquisition leading to the Bilino Polje Abjuration was started by an accusation of heresy, the abjuration itself contains no mention of any heretical actions. Instead, it had Bosnian bishops declare their loyalty to the Roman Catholic Church, accept Roman Catholic priests and supremacy, required use of the Roman Catholic liturgy and benedictions and Roman Catholic rites. It also demanded that the cross and altars be replaced in the Bosnian Catholic churches. The closest thing to a mention of dualist heresy in Bosnia was language which forbade the offering of shelter to “Manichaens”.

Problems in the Bosnian flock were attributed to an involuntary ignorance of Catholic doctrine and practice, and attempted to correct it by condemning any deviation from official practice. Pope Innocent III himself called Ban Kulin an “Obedient Son of the Church”, and no contemporary sources ever referred to him as anything less than a devout Catholic.

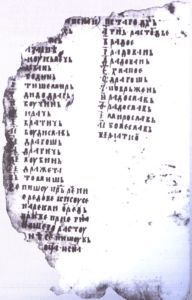

However, Bosnian anger simmered over the invasion of their home and being forced to prove their religious adherence. When the Pope replaced their Slavic bishop with a Hungarian bishop and transferred Bosnia to the archbishop of Split rather than Dubrovnik, Ban Kulin responded by ignoring the whole incident. Bosnian clergy obviously felt that they needed to assert their own identity as well, as one of the few remaining religious books from the Bosnian Church, the Hval Gospel, includes a list of bishops – three of whom also signed the Bilino Polje Abjuration.

By 1227 Pope Honorius III was again trying to drum up support for a crusade against “Bosnian heretics”, and in 1233 Dominican inquisitors were sent to again investigate the religion of the region. Despite the fact that the newest legate, Jacob de Pecoraria, found no evidence of heresy and attributed the issues to ignorant clergy yet again, a crusade against Bosnia was launched in 1235, led by the Hungarian noble Coloman. It lasted until his death in 1241, when the Mongol invasion created devastation everywhere in the Balkans but Bosnia.

Reports from the crusade of Dominicans burning Bogomils at the stake were the final nail in the coffin of relations between the Bosnian Church and Rome. The Roman Church pulled up stakes, moved its seat from Vrhbosna (now Sarajevo) to Đakovo in Croatia and nominally put a Hungarian in charge of the Bosnia area. Although there would not be another crusade into Bosnia, the schism between the two churches was in full effect.

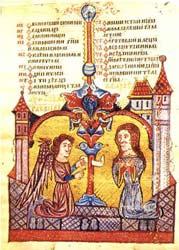

Although it is easy to see the base structure of the Bosnian Church as being descended from Roman Catholicism, there are uniquely Slavic traits that define it. Liturgy was recited in Slavonic. The bishop of the church was called Djed (Slavic for grandfather). Directly below the Djed in the hierarchy were Gosti (Slavic for guests). Gosti were responsible for arranging ministrations and for conducting the liturgical meetings when the Djed was not present. They were also generally in charge of monastic groups. The Strojnici were priests under a Gost, and a council of twelve strojnici would advise him. Finally, the Starac was the head of the local Krstjan (members of the Bosnian Church referred to themselves as Krstjan) community, referred to as the Hiža.

There was, as well, a famous center of learning sponsored by the Bosnian Church in Moštre called The House of Krstjani.

Differing from the Roman Catholic church in that the Krstjani did not have territorial organizations, or parishes; they also did not deal with secular matters other than burials with very few exceptions. King Stjepan Ostoja was known to be advised by the Djed between 1403 and 1405, and Krstjani were sometimes used as mediators or in diplomatic positions. The Bosnian Church was also not as active in the lives of the peasants as was the Roman Catholic church, however, by 1340 nearly all Bosnian nobles were also members of the Bosnian Church.

Of the sixteen medieval Bosnian rulers, six were members of the Bosnian Church, five were Roman Catholic, four changed their religion before or during their rule, and only one is still of ambiguous beliefs. The fluidity of exchange between the two churches seems to suggest that 1) they were more alike than different, and 2) Bosnian rulers were more interested in maintaining peaceful relations between the various churches in their realm than in promoting evangelism. In retrospect, it was a policy that would have done well to have been continued for several centuries to avoid the bloodshed of the 1990s.

Pressures from the outside refused to allow the Bosnian Church free reign, however. For one thing, the Ottomans were beginning to exert pressure on the borders as they surged through the Balkans. For another, the Hungarian Empire never quite accepted the loss of their Bosnian territory. When King Stjepan Tomas desperately needed help to defend his kingdom from the Ottomans, the Hungarians agreed – for a price. That price was the brutal re-Catholicizing of the Bosnian population.

Stjepan Tomas agreed, and in 1459 members of the Bosnian Church were given the choice of conversion or banishment. Most chose conversion, and the Bosnian Church was ended. It was only a surface conversion, however. Quite fed up with the constant persecution of the Hungarian Catholics and their high taxes, the Bosnian population didn’t put up much of a fuss when the Ottomans came roaring into the country, conquering everything before them. And, having had their Bosnian religion violently rooted out in the earlier decades, the Bosnian people proved to be a fertile ground for conversions to Islam.

Bosnia proved to be just as stubborn in its conversion to Islam as it had been for the Roman Catholics, however. Stecci, the beautiful stone grave markers unique to the region, were adapted and their use continued in Islam. Mosques and their minarets were constructed of wood. The local rakija and beer were not shunned, despite Muslim prohibitions of alcohol.

With the coming of the Ottoman tide, a new religion washed over Bosnia. It did not, however, wash away the core of religious practice in the Balkan crossroads.

- June 23, 2020

- Bosnia and Herzegovina