A Defining Crisis

“Don’t compromise the future with hasty reforms, and don’t replace the structures that Belgium hands over to you until you are sure that you can do better. Don’t be afraid to come to us. We will remain by your side and give you advice.”

With those most patronizing of words, King Baudouin I of Belgium spoke at the 30 June 1960 independence celebration of Congo in praise of the advances made under colonialism. He went further, praising King Leopold II- who had ordered the colony ruled with an iron fist and the hands of those who gathered rubber too slowly were summarily chopped off – as a “genius”.

It can be understood, then, why the first Prime Minister of the Congo, Patrice Lumumba, felt it was imperative to reply even though he had not been scheduled to make remarks.

“For this independence of the Congo, although being proclaimed today by agreement with Belgium, an amicable country, with which we are on equal terms, no Congolese worthy of the name will ever be able to forget that it was by fighting that it has been won, a day-to-day fight, an ardent and idealistic fight, a fight in which we were spared neither privation nor suffering, and for which we gave our strength and our blood. We are proud of this struggle, of tears, of fire, and of blood, to the depths of our being, for it was a noble and just struggle, and indispensable to put an end to the humiliating slavery which was imposed upon us by force.”

The Western media did not take well to Lumumba’s remarks, seeing them as a call to arms for Belgo-Congo hostilities. Nor did King Baudouin ever forget feeling humiliated by Lumumba that day, a consequence that was to have significant unforeseen consequences in January 1961.

But Baudouin was not the only white person affected by Congolese independence that resented the whole switch-up. Although independence was settled, colonial policies pre-independence had done nothing to prepare the Congo for eventual self-rule. Access to education for non-whites was difficult, and although the Belgians had put efforts into creating a middle-class and educated indigenous layer of society, called évolués, there were not nearly enough Congolese with the education to take over the myriad government and military positions necessary for a functioning government. The Belgian government also resisted giving native Congolese any but the most menial of positions, leading to a total lack of experienced leadership, even amongst the évolué class. Native Congolese were not allowed to vote until 1957, and there was a ban on assembly, restrictions on their freedom of speech, and restrictions on travel within and out of the colony. In short, Belgium was completely unconcerned with preparing their colony for independence, and actively seemed to attempt to set their self-rule up for failure.

Because there were not enough qualified Black Congolese to take over government and military positions, white officers and civil servants were to remain in Congo in order to facilitate the government’s function, particularly in the rich mining areas of South Kasai and Katanga, as well as in the Congo military – the Force Publique. It was the Force Publique that was to set off the next five disastrous years.

Black Congolese expected to see an immediate effect on the quality of life for them – including opportunities for advancement. Although Congolese cadets had been sent to train in Belgian military academies, as of yet there were still no Congolese officers in the Force Publique. It remained a white cadre commanding a black military. And when the commander of the Force Publique, Émile Janssens, wrote during a briefing of white officers, “BEFORE INDEPENDENCE = AFTER INDEPENDENCE” on 5 July 1960, it sparked a mutiny.

When the mutiny began to spread, and the Congolese army began to attack whites, loot white businesses, and rape white women, the Belgians saw the entire situation as a justification of their concerns about Lumumba and his leadership. The entire escalation was blamed on the “radicalism” of the Congolese Prime Minister. Less than two weeks after handing over the government of the Congo to its natives, Belgium felt they had no choice but to intervene.

On 9 July 1960, Belgian paratroopers were unilaterally sent into the Congo to defend and evacuate the white civilians in the country. It was an action that was taken without any consideration as to the feelings of those in a sovereign nation who would watch helplessly as members of the military of another country sweep in without so much as a by-your-leave. Lumumba was furious, but he informed the Belgian government that the military could remain only to protect citizens, and just cease all activity as soon as order was restored. It wasn’t enough. As a consequence of of the unrest and recommendations from Europe, 10,000 European civil servants abruptly left the Congo. The government was paralyzed.

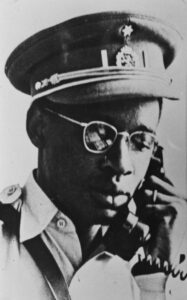

Lumumba was already trying to address the mutiny issues, and by 8 July was actively in the process of Africanizing the garrison. Émile Janssens had been relieved and replaced by Victor Lundula as the Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces, and his chief of staff was the newly promoted Colonel Joseph-Désiré Mobutu. No longer the Force Publique, the military was now named the Armée Nationale Congolaise (ANC). Lundula made intensive effort in his position – intervening in riots and personally rescuing Europeans from harm.

But the efforts of Africanization were not enough. Lumumba’s political party, the Mouvement National Congolese, was the largest contemporary political party not based on ethnic lines, but representing the entirety of Congolese society. Unfortunately, it was also rent with dissension. Under the nationalist umbrella were a multitude of varying political dogmas, Lumumba was criticized for being too radical, but also for not being radical enough. While the operation of government was paralyzed for lack of trained civil servants, the upper levels of government were experiencing their own paralysis and inability to work together.

This was compounded further on 11 July when the Katanga region declared themselves separate and then again on 8 August when the “Mining State of South Kasai” also seceded. As Moise Tshombe, leading Katanga, said, “We are seceding from chaos.” And in doing so, they were supported by Belgium, who wished to keep their access to the vast amount of resources Congo could offer. These secessions deprived the Congolese government, already in dire straits monetarily just out of the gate, of 40% of the nation’s revenues. Lumumba could not let these areas go.

As Congo secessionist fighting ramped up, the United Nations Security Council acted in an attempt to encourage peaceful settlement of Congo’s issues, a thorny issue to attack, as the Secretary General Dag Hammarskjold was adamant that the UN not take sides in the internal matters of sovereign nations as set out in Article 2 of the UN charter. The result was the July 14 Security Council Resolution 143, voted for by both the United States and Soviet Union, which authorized the UN to send troops in order to facilitate the withdrawal of Belgian troops. The Belgian troops were seen as a large part of the reason for Congo’s quick descent into chaos.

Lumumba initially welcomed the UN troops, but was quickly disabused of the notion that they would help turn the tide of the rapidly deteriorating situation in the breakaway provinces. Hammarskjold would not relent – to interfere in the internal political matters of Congo would breach UN impartiality and Congolese sovereignty. The UN was only in the Congo to maintain law and order.

Seeing few options, the Soviets were asked for help and they responded promptly. One thousand Soviet advisors soon landed and involved themselves in the fight against the Katanga rebels.

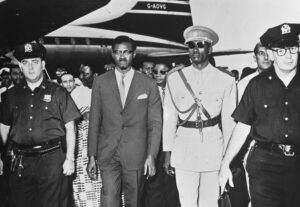

Lumumba had no illusions that the situation in the newly independent Congo could fix itself. On 22 July he departed to make his case in person at the United Nations. From there he went to Washington, DC where he spoke to the Secretary of State, requesting help to right the affairs of the Congo so that it could gain its footing and move forward a a free nation, without continuing interference from Belgium.

From the official Memorandum of Conversation with Secretary of State Christian Herter, Lumumba expressed faith in the ability of the United States to help the nascent state:

The Prime Minister replied by expressing the emotion which he and all members of his delegation had felt in response to the welcome afforded them at the airport. This gave them, he said, the impression that the United States recognized the Congo on the same footing as any other sovereign state and that among the various difficulties the Congo faces, they know that they will find the aid they desire from the United States. He said that the people of the Congo have enormous confidence in the United States even in the most remote villages, and they know that the United States is anti-colonialist. The Prime Minister went on to say that the struggling of the Congolese had been only against a particular regime and that all who struggle for liberation are treated like bandits. The colonizers are able to present their version of the anti-colonial stories in the international press, leaving the other side silent. He remarked that the Congo can only build its independence with the help of the civilized world but that in so doing should be careful to ask themselves exactly what the aims are of the various countries offering assistance. He said that the Congo must be vigilant in consolidating its independence.

The United States, however, was already holding a more negative view of the Congo government than Lumumba counted on, as the Belgian government had been strident discussing the violence and rapes being committed by the ANC. Further, Belgium’s claims to Lumumba’s communist leanings seemed clear, as his invitation to the Soviet Union seemed to suggest. It was clear that help would not be forthcoming from the West.

Lumumba departed the United States and made his way home, via several African countries where meetings with leaders convinced him that help, militarily and otherwise, could be counted on in those quarters. He reached home on 8 August, ready to act decisively.

On 9 August Lumumba declared a state of emergency, which outlawed the formation of groups and clubs without government permission, gave the government the right to seize and suspend publications (which they did almost immediately to the Courrier d’Afrique after arresting its editor), and established military tribunals. Lumumba also expelled the Belgian diplomats under penalty of arrest, and recalled all Congolese students studying in Belgium.

Lumumba began to feel increasingly isolated and unable to tell what was truth and what was manipulation. He stopped seeing anyone but his most trusted advisors and making decisions based on rumors and suspicion.

It was based on this behavior, according to President Kasavubu, that he acted to remove Prime Minister Lumumba from office of 5 September.

The removal, although solely a Congolese matter, was helped along by the UN Representative in Leopoldville, the American Andrew Cordier. Cordier used his position to block radio broadcasts, thus keeping pro-Lumumba efforts from coordinating a quick response.

Kasavubu’s action was not legal, and Lumumba fought back. Both houses of parliament, whether individual members held support for Lumumba or not, were opposed to his removal. Lumumba, disavowing the action, ordered Kasavubu removed. The factions were so mired in argument and counter-argument that no headway could be made.

Which was the reason that Colonel Joseph-Désiré Mobutu gave on 14 September when he took over the government in a bloodless coup, removing both Lumumba and Kasavubu. In his radio address announcing the action, Mobutu said that the day-to-day operations of government would be addressed by “technicians,” later expanded upon to be the Collège des Commissaires-generaux. Further, all Soviet advisors were advised to leave, and Eastern Bloc nations were to close their embassies. Lumumba himself was placed on house-arrest.

Mobutu seemed to come nearly from out of nowhere, but he had been quietly amassing power behind the scenes. The United States had quietly passed $1 million to the Congolese government to pay troops, in an attempt to keep further deterioration at bay. Mobutu, the recipient of these monies, used them to build loyalty amongst the ANC. It was the support of the ANC that made Mobutu’s moves toward power meaningful.

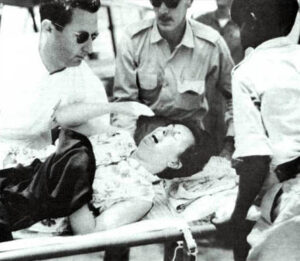

Lumumba protested his conditions under house arrest strenuously, and at the end of November he managed an escape. Although the area near Stanleyville was filled with supporters awaiting his arrival, he delayed along the way by visiting villages and locals. Mobutu’s soldiers caught up with him on 1 December. Even then, Lumumba was already across the river and could have escaped, but he feared for the safety of his wife and child. He re-crossed the river to fetch them. His 23-year-old wife, Pauline Opangu, watched as he was arrested, beaten, and dragged away.

The Soviet government immediately registered a protest at Lumumba’s treatment and demanded his release. By 14 December a pro-Lumumba UN resolution was put up, but it was defeated in a vote. Colonel Mobutu and the Congo government had their answer from the world.

On 17 January 1961, Patrice Lumumba was taken from Leopoldville to Elisabethville and tortured. He was then taken to an isolated area, stood against a tree, and shot. His corpse was dug up on 21 January, sawed apart with a hacksaw, and dissolved in sulfuric acid.

His death was finally announced on 13 February, initially attributed to a rage attack by other prisoners. No one believed the government’s announcement.

The day after his death was announced, Lumumba’s widow walked through the streets of Leopoldville bare-breasted and carrying her youngest son, to the offices of the UN Representative with 100 of Lumumba’s followers to ask for her husband’s body. She wanted to give him a Christian burial.

In other countries protests broke out at the news of the murder. In Yugoslavia, protestors stormed the Belgian Embassy in Belgrade. But this did not dissuade the political violence happening within Congo- and seven additional Lumumbists were executed.

With the execution of Patrice Lumumba, there was no backing off from the precipice. Awash with ethnic rivalries and political factions, having invited the involvement of both of the two major powers of the Cold War, the Congo Crisis stretched into five increasingly violent years that would culminate in one of the most corrupt kleptocrats in the history of Africa and human rights abuses that are still being uncovered nearly sixty years after they were committed.

On 18 September 1961, one year after Mobutu’s first coup, UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjold was killed in a plane crash near Ndola in what is now Zambia. He was on his way to try and broker a peace between the Congolese government and the break-away Katanga province. Initial investigations attributed the crash to pilot error, but rumors persist still that there was interference from either another plane or from something shot from the ground.

Hammarskjold’s death ushered in a new Secretary-General, U Thant, who was more receptive to UN forces intervening to prevent human rights abuses and full scale civil war. The United Nations Operation in the Congo (UNOC), its mandate expanded by UN Resolution 169 in November 1961, would involve 20,000 troops and support from over 30 countries.

Atrocities continued: the Kindu Massacre of Italian pilots in November 1961 drove home what UN troops would be facing – as the pilots were beaten, murdered, and then hacked to pieces by machetes. Nor would the conflict remain localized: UN troops were present, as well as Soviet and Cuban advisors to the rebels. White mercenary troops were also brought into the conflict.

Hostage-taking became a regular occurrence, culminating in the November 1964 Operation Dragon Rouge, where Belgian and US forces descended to rescue the Europeans being held by the rebel Simbas. Over 1600 foreigners and 150 Congolese were evacuated, to which the Simbas responded by killing 185 foreigners and 2000 Congolese.

On 25 November 1965, Colonel Joseph-Désiré Mobutu executed a second coup. Like the first, because he had the full support of the ANC, it was bloodless. The coup was welcomed by foreign powers, as it promised economic and political stability and the world was weary of the endless fighting in the wilds of Africa.

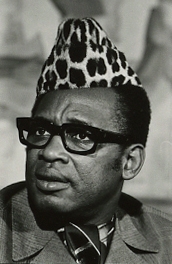

Mobutu declared a state of emergency that was to last for five years. In increments he consolidated his power and created a highly centralized state, abolishing the office of the Prime Minister in 1966 and Parliament in 1967. He instituted a campaign called “authenticite”, an attempt to eliminate all foreign influence from Congo, which included both his name and the name of the country. Colonel Joseph-Désiré Mobutu became Mobutu Sese Seko, and Congo became Zaire.

He created a personality cult with such outlandish examples as building his own Versailles in the jungle, and chartering shopping flights aboard the concorde to Paris. The famous “Rumble in the Jungle” fight between George Foreman and Muhammed Ali happened in the renamed Kinshasha in 1974. He even appropriated the “right to deflower” on his trips across Zaire, with village chiefs offering him local virgins. The families of these girls were supposed to be filled with honor.

And, of course, there was Mobutu’s omnipresent leopardskin hat.

The Mobutu era would end in 1997 when a coup by Laurent Kabila ousted the aging dictator. Mobutu, already dying of cancer, would succumb only a few months later in September 1997 in Rabat, Morocco.

Although there have been pretenders to the crown, the current whereabouts of his actual leopardskin hat are unknown.

- August 30, 2020

- Congo