A Queen’s Death

The murder of the queen had been represented to me as a deed lawful and meritorious. — Anthony Babington, executed for his part in the Babington Plot to assassinate Queen Elizabeth I of England

It’s a strange turn of events that when assassinations are discussed, the discussion rarely includes the Hungarian Queen Elizabeth of Bosnia; who not only took part in an assassination herself, but was one year later assassinated in turn in 1387.

Elizabeth was born into Balkan nobility. Her father Stephan Kotromanović was the Ban of Bosnia. Her cousin Tvrtko was his heir, and the first independent King of Bosnia. Her mother was a member of the Polish nobility and a cousin of the Queen Mother of Hungary. All of this combined to push Elizabeth into marriage with Louis I, King of Hungary on 20 June 1353 when she was about 14-years-old.

It certainly didn’t help matters after her wedding when her father died within months and her cousin Tvrtko succeeded him; Louis I, who was the nominal overlord of Bosnia, was not a fan. His inclination toward dislike was a prescient one; Tvrtko would cause the Hungarian rulers no end of irritation and trouble. He even managed to cause the Pope such irritation that in 1360 a letter was sent from the Pontiff to Louis I and Elizabeth asking her to intercede with her cousin who was in the process of forcing a Catholic noblewoman to marry a “schismatic” member of the Bosnian Church.

Elizabeth’s first seventeen years in the Hungarian court passed unremarkably. She was completely dominated by her mother-in-law, Elizabeth of Poland. She had no surviving children and was widely considered to be barren. But as soon as her mother-in-law left to assume the regency for her son in Poland in 1370, Elizabeth was able to deliver a healthy baby girl named Catherine. Two more girls followed in quick succession: Mary in 1371 and Hedwig (Jadwiga) in 1373 or 1374.

It’s hard not to attribute her ability to bear healthy children to the lack of a domineering mother-in-law in her general vicinity, but no real records of any such whispers at court remain. In any case, Elizabeth’s childbearing ended, most likely due to age, two years before her mother-in-law returned from Poland, fleeing the nobles who had murdered 160 of her retainers. Such a disgrace did not allow her easily back into the role of leading lady at the Hungarian Court.

Beside the Queen Mother’s humiliation in Poland, another strike against her was that during her absence Elizabeth of Bosnia had not only delivered heirs to the throne, but had begun to take part in the political maneuverings of the day. Accustomed to the help of his mother in ruling, Louis I began to consult Elizabeth instead, and her political star ascended quickly.

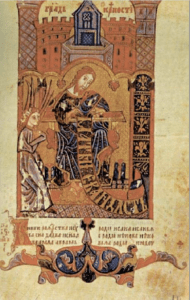

One indication of this can still be seen at the Church of St Simeon in Zadar, Croatia where Elizabeth commissioned a reliquary to hold the body of St Simeon. Donating reliquaries was not unusual for a Queen, and Elizabeth’s mother-in-law had been renowned for her donations to saints’ shrines. But the actual reliquary itself shows an example of just how powerful Elizabeth had become at the court.

Zadar was strategically hugely important to the Hungarians, and it tended to move back and forth between Hungarian and Venetian control. In 1345 the combined armies of Louis I of Hungary and Elizabeth’s father Ban Stephan Kotromanović beat back a siege in Zadar only to relinquish the city back into the hands of the Venetians. At the time this was blamed on Ban Stephan, who was called a heretic and a traitor and said to love Venetian money more than battle (an accusation of cowardice).

In 1358, five years after Stephan’s death, Zadar came back under Hungarian control with the Treaty of Zadar. True to history, though, it didn’t remain out of contention long. By the 1370s conflict was brewing between Venice and Hungary again, and in 1378 there was another war. There needed to be a way to get the citizens of Zadar fully behind the reign of King Louis I.

Elizabeth’s reliquary was designed to do just that. It was a piece of enormous ostentation and something that could only be donated by a person with the resources of the Queen. Having a peaked roof (to keep worshippers from laying atop it), it was carved in its entirety with scenes showing the history of Zadar as a city of God, including scenes featuring Elizabeth and her three daughters. The engraving referred to Elizabeth as being

“powerful, illustrious, and exalted” as well as featuring themes that tended to be masculine in nature. The message of the reliquary was not only to the citizens of Zadar, but to Elizabeth’s relatives as well. She was powerful, and not to be dismissed.

The reliquary served one more important purpose – it separated Elizabeth from the heresy of the Bosnian Church, a heresy her father and cousin Tvrtko tolerated. Elizabeth was showing herself as a devout, traditional Catholic.

The story that she had the reliquary built as penance for attempting to steal the saint’s finger (to assure the birth of a boy when she was pregnant in 1371) is supposedly illustrated on the chest, but there are arguments against that particular explanation of the representation. It’s possible that the story is true – but it is also possible, given the later events – that the story was used to discredit a woman who had amassed too much overt power for one of her gender.

Louis I inherited the title of King of Poland in 1370, and as his successive daughters were born, he continued to maneuver them into upwardly mobile marriages and secure their inheritances and crowns. There is also early evidence that Elizabeth herself was an involved mother: she wrote a book for the education of her daughters. No copies of the book remain, but the mention of one sent to France preserves the fact that they existed. The book must have been impressive, the oldest daughter Catherine was betrothed to the son of the King of France. Mary was betrothed to Sigismund, the son of the Holy Roman Emperor, and Hedwig to William of Austria, a Habsburg heir. The very young Hedwig was sent to the court in Vienna to be raised as a proper Habsburg before her marriage.

Tragedy was stalking Elizabeth of Bosnia, however. In 1378 her oldest daughter Catherine died suddenly. Louis’s plans for passing on his thrones would have to be changed. And Louis himself was also weakening in sickness. He survived Catherine by four years before dying in 1382.

The five years between Louis’s death in 1382 and Elizabeth’s own death in 1387 were more chaotic than any other period of her life. Elizabeth had grown used to wielding power and was not willing to cede any of it to her prospective son-in-law and his family. Without waiting, she had her daughter Mary crowned King of Hungary on 17 September 1383, only seven days after the death of Louis. The female Mary was a King rather than a Queen in order to prevent Sigismund from seizing the government after marriage.

But Elizabeth still did not feel secure. Her Hungarian nobles were showing unrest at the thought of being ruled by the 11-year-old Mary and Elizabeth’s power behind the throne. To strengthen her position, Elizabeth took advantage of the papal schism and had Mary’s betrothal to Sigismund invalidated by Pope Clement VII and married by proxy to Catherine’s former betrothed.

The marriage-by-proxy set in motion a chain of events that would end in Elizabeth’s murder.

Obviously Sigismund was unhappy with Elizabeth’s choices in regards to King Mary, and he prepared an invasion using as evidence the fact that the other pope, Pope Urban VI, held Pope ClementVII’s dispensation as utter hogwash.

Sigismund returned to Hungary and married Mary in August of 1385, but soon had to flee as Charles of Durazzo and his Italian allies invaded. His armies reached Budapest in December 1385 and the Diet forced Mary to abdicate and crowned Charles as Charles II on 31 December. Mary and Elizabeth were forced to participate in his coronation ceremony.

But Elizabeth still had a plan, and she still had her foremost supporter Nikola Garaj. After Charles’s Italian allies withdrew from Budapest, she invited the new king to Buda Castle. He accepted on 7 February, and in her presence was fatally stabbed by Elizabeth’s retainers. Charles of Durazzo died on 24 February 1386, and Mary re-assumed her role as King.

The Hungarian and Croatian nobles were not any less assured by the assassination of Charles II, and in several cases it caused allied families to break and rebel. Against all advice, Elizabeth felt the only way to bring the other nobles to heel was to expose them to Mary. The Queen and the King would travel to the troubled area to bring the wayward nobles back into the fold.

It was a disaster. On 25 July 1386 Mary and Elizabeth were ambushed by the troops of John Horvat in Gorjani. The loyal Nikola Garaj fought valiantly to free the two women, continuing the fight even as his chest bristled with arrows, which he broke off while still embedded in order to not block the movement of his sword.

When Garaj dismounted in order to slash at the attackers in closer quarters, some of them snuck behind the carriage to reach under, pull the warrior backward, and summarily beheaded him.

His severed head was tossed into the carriage with Elizabeth and Mary, and the two queens were imprisoned in Gomnec. Elizabeth took all the blame for the rebellion, begging her captors to spare Mary’s life.

Margaret, the wife of Charles of Durazzo, demanded Elizabeth’s death. But Elizabeth was not killed on her command; a trial was held after a move to Novigrad Castle in December 1386 and Elizabeth was found guilty of inciting Charles’s murder.

There was no hurry to put Elizabeth to death. It wasn’t until the Horvats received word that Sigismund was on his way with an army to rescue the women in January 1387 that Elizabeth was strangled to death in Mary’s presence.

Mary was rescued and returned to her husband on 4 June 1387, and although she retained her crown it was Sigismund that ruled… with one exception.

In 1394 Mary had the captured John Horvat tortured and executed as the man responsible for the murder of her mother.

Elizabeth of Bosnia has been consigned to the periphery of history, despite the enormous amounts of power she wielded at a time when women had to be very careful how they demonstrated power. She is often described as being inept politically and a disastrous ruler – both of which may be true. But it is also true that male rulers often undertook the same actions as Elizabeth and were not penalized for doing so either by contemporaries or by modern interpretations of the historical record.

Perhaps Elizabeth’s tragic destiny was shaped more by her gender and the times she was born into than by any inherent political ineptitude.

To read more about Balkan history, please click here.

- June 4, 2021

- History