A Tale of Two Churches

“At first we were confused. The East thought that we were West, while the West considered us to be East. Some of us misunderstood our place in the clash of currents, so they cried that we belong to neither side, and others that we belong exclusively to one side or the other. But I tell you, Ireneus, we are doomed by fate to be the East in the West and the West in the East…” Saint Sava, Thirteenth Century

Everyone knows about religion in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and almost no one knows. Everyone knows that tension between Catholic Croats, Muslim Bosniaks, and Orthodox Serbs exploded in the 1990s. Some people know that fifty years before the war in the 90s there were also large numbers of Jews, welcomed by the Ottomans after expulsion from Spain, fully a part of society in BiH. Other people might know about the Kingdom of Bosnia’s penchant for welcoming fleeing heretics from other parts of Europe, and maybe even have a name for them: The Bogomils. Fewer still people know about the native Bosnian Church.

But even that is all so simple. Unfortunately, life is rarely able to be condensed into simple categories. It is, though, a place to start.

The Bogomil Heresy developed in Bulgaria (the part of then-Bulgaria that is now-Macedonia) in the tenth century, most likely through a priest made Bogomil, although the meaning, “Dear to God”, is exactly the kind of naming convention for a new religion that adherents are attracted to. Although later the Bogomils would be persecuted heavily, there is some evidence that Samuil of Bulgaria (who reigned from 976 to 1014) had their support in his rebellion, and there were no persecutions of Bogomils during his reign.

Bogomilism likely came about for a few reasons, almost all of them pointing back to an Orthodox church that had become deaf to the needs of its adherents, corrupt, and dismissive of its followers. At this time, the Orthodox Church liturgy was still read in Greek, which none of the peasants spoke or understood. Language is a tremendously powerful motive, and when added to a mix containing resentment over high taxes and abuse by nobles, it began to tip toward a religious revolution. An earlier heresy from Armenia, Paulicianism, was waiting in the wings to influence the angry peasantry. Greatly influenced by the Paulician beliefs, Bulgarians began to be swayed to a new set of beliefs that allowed them to refuse to pay taxes, refuse to work in serfdom, and refuse to serve in conquering wars.

Understandably, this infuriated rulers of any area where Bogomils (a very evangelical group) began to concentrate. They needed taxes and armies to continue to function in their feudal society. In the 1100s, the Bogomil persecutions began in earnest throughout areas where the Orthodox Church held sway and into areas of the Latin (Catholic) church, sweeping another, lesser known, church away with it.

Bosnia in the 1100s was not yet a kingdom, but its mountainous and wild terrain gave it a high degree of independence from its overlords: first the Orthodox Byzantine Empire, then the Catholic Hungarians. Further, it was completely surrounded by nations with warring religious beliefs, the two largest being Orthodox Serbia to the east and Catholic Hungary to the north. Bosnia was in an ever-precarious position in a time of religious conquest.

It was during the 1100s that the ruler most celebrated for leading Bosnia’s Golden Age, Ban Kulin, came to power. And it was under Ban Kulin that the roiling cauldron of religious sentiment came to its first boil.

All Papal sources of the time describe Ban Kulin as a devout Catholic. There was no question amongst the powers-that-be of his religious loyalties. However, he had allowed the Bogomils being chased out of Serbia, Bulgaria, and the present area of Herzegovina to settle peacefully in his banate, and Bogomils were heretics. Further, the church in Rome had received reports that heresies were also being practiced by the Bosnians themselves.

“Ludicrous!” Ban Kulin replied, and offered to allow Inquisitors to inspect the country and question the nobles. The result of this inquisition, the Bilino Polje Abjuration of 1203, made no mention of any heresies amongst the Catholicism professed by the Bosnian people, although it did read something like an exasperated teacher explaining exactly how a Catholic was supposed to worship, and required Ban Kulin to refuse entry into his banate to any heretics.

Bosnia, as has been its practice ever since, promptly went back to whatever they were doing before as soon as the Papal Legate left as though the agreement didn’t exist and continued on in that way for the next approximately 300 years.

But what was the Bosnian Catholic church doing that had the church in Rome so ginned up?

Bosnia itself was mostly illiterate, and it existed on the border of the two major Christian denominations. It had also jumped between Orthodox and Catholic rule. It was remote, and it supplied its own bishops. The most likely explanation is that the Bosnian Catholic Church was a fusion of Orthodox and Catholic beliefs, celebrated mass in the Bosnian language, and that the area’s peasants had thrown in some old pagan practices and magic for good measure.

“Bosnia was a frontier land between the spheres of the Greek and Latin churches. To the north, the Kingdom of Hungary was an outpost of the Latins; farther south, Serbia represented Orthodox tradition; and along the coast Trogir, Split, and Dubrovnik were Catholic. The interior of Bosnia, with its forests and mountains, was an ecclesiastical no-man’s-land in which neither of the churches had effective jursidiction.” Malcom Lambert

There were no contemporary mentions of the church having Bogomilist doctrines, and no Catholic source at that time refers to them as Bogomils, although the term was certainly in use and understood to refer to a specific heretical sect. Had the Roman church believed that Bosnia was falling under the sway of the Bogomils, they most certainly would have mentioned it as they did in other areas where they chased the heretics out.

Unable to leave good enough alone, the Catholic Hungarians began to agitate more and more about what they called heresies taking place in Bosnia, and after the Bilino Polje Abjuration they were finally granted permission for a Crusade in 1234. In the meantime, the local Bosnians were quite sick and tired of the Hungarians always trying to invade, and the indigenous version of the Catholic Church began to take root and a shape of its own.

The most likely reason that the Bosnian Church and the Bogomils became conflated is that both were known to exist in the same time and place and most of the written records of both were destroyed during their respective persecutions. Enough remained, however, to study and compare.

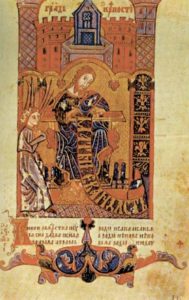

One major document, written in the Bosnian alphabet of Bosančica, is the Hval Gospel. This was seized during the Bosnian Crusades and Inquisition and still resides in Italy. The Hval Gospel is known to have been used in church services. It contains a complete New Testament, the Ten Commandments, and the Psalms. It also contains an illustration of John the Baptist and one of Christ on the Cross.

Bogomil beliefs were dualist, that both good and evil exist and have existed from the beginning. Because they believe that God created souls but Satan created the universe of matter, they believed that the Old Testament was inspired by Satan. While Christ was sent by God, the cross he died on was from Satan. Knowing this, it is extremely unlikely that a book with illustrated pictures of the cross and the Old Testament was used to celebrate Bogomil worship.

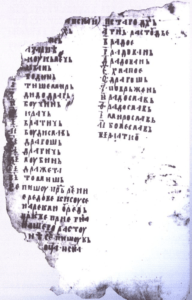

Having established that the uniquely Bosnian prayer book was not Bogomil, and therefore an example of a distinct and different Bosnian Church, another inclusion in the document is of interest: a list of bishops in the Bosnian Catholic Church. A list with several names that corresponded with the same priests who had signed the Bilino Polje Abjuration under Ban Kulin.

For all the complaints about heresies in the Bosnian Church, the Church in Rome itself had inspected several of the men who would later become bishops and found them to be Catholic and in accord with Catholic belief. The Bosnian Catholic Church was not related to the Bogomils. So why, then, the persistence by the Hungarians of constantly calling for Crusades against heresies in Bosnia?

Power. Like most major events, the actions against Bosnia most likely came down to power. Accusations of heresy against the church was a quick and easy way to get the support of Rome behind what was really a movement to seize land or raise taxes. The Bosnians made it easy enough with their mash-up of Catholicism and Orthodoxy and their folk-beliefs thrown into the mix. Further, Bosnians were practical people, and they were more concerned with church practices than with church doctrine. If they took communion as the church demanded, attended available services at the prescribed time, and admitted to the leadership role of the priest, they were Christian. Fertility rituals and formerly pagan celebrations had nothing to do with the God that they worshipped, they were things that had always been done for the good of the community and would be continued on for that same reason.

In the fifteenth century, as the Ottomans came ever closer, Bosnian kings appealed with more and more desperation to the Hungarians. The Catholic Hungarians agreed to help with protection against the Muslim incursion, but demanded a steep price: the Bosnian Church, as heretics, must be rooted out completely, whatever it took. In 1459 King Stjepan Tomas gave Bosnian Catholics a choice – convert or go into exile. Most of them converted.

Stjepan Tomas then contented himself with seizing Bosnian Church properties and wealth, not understanding that in abolishing the church in which his subjects were most comfortable and allowing a Catholic Hungarian empire to dictate religion and raise taxes on his fiercely independent people, he created a religious vacuum that the Ottomans and Islam were happy to fill before five years had passed.

The Ottomans didn’t care about different Christian sects, but by the time they arrived the damage was done. There were no more Bogomils, and the Bosnian Catholic Church had been unmoored by its own leader. The two ceased to exist, and weren’t a part of general conversation again until the end of the nineteenth century and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which needed to find a way to separate Bosnian identity from Serbia. A past in which Bosnians had been persecuted to the point of religious conversion fulfilled that need – particularly because it was propaganda based heavily on truth. To further sweeten the deal, there were very few things left which could prove who was what, believed what, did what, or ruled what. Thus the Bosnian Catholic Church and the Bogomils became equated in the pop culture of the world for nearly 100 years and only recently has a fuller truth emerged about the tradition of religious plurality in Bosnia.

- June 18, 2020

- Bosnia and Herzegovina , Bulgaria