When the Children Led

“Natives must be taught from an early age that equality with Europeans is not for them,” Dr. Hendrik Verwoerd, author of the Bantu Education Act.

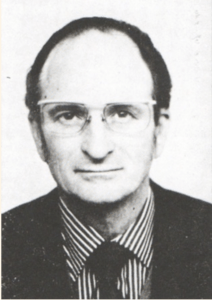

In 1971, sociologist Dr Melville Edelstein, who devoted 18 years of his life to working in Soweto to improve conditions, wrote a book called “What Young Africans Think,” about the rising levels of black African anger. No one paid attention.

What the apartheid government of South Africa did pay attention to was the fact that Black Africans were learning to speak Afrikaans in dramatically dropping numbers and choosing to learn English in schools. To address this fact, the government decided to make it mandatory for at least half of all school subjects to be taught in Afrikaans. If black students didn’t choose Afrikaans, it would be chosen for them, as dictated by the Afrikaans Medium Decree of 1974. As government leaders pointed out – Black students might work on farms or in factories where bosses could give orders in English or Afrikaans, and students should be able to understand either. Somehow, it seemed perfectly reasonable to the government.

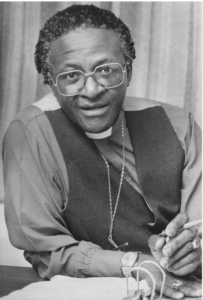

It was hated with a seething resentment by the African community. Aside from the humiliation of being forced to learn what was referred to by Desmond Tutu as “the language of the oppressor,” it also forced students to focus more on learning the language than developing the critical thinking and analysis skills necessary for an advancing education. It was yet another way to keep black South Africans from advancing.

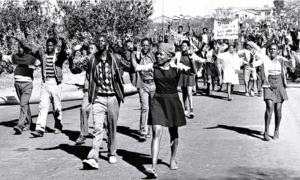

On 30 April 1976, students in Soweto had enough. They called a strike. Soon, students throughout the township were refusing to attend school. The Soweto Students Representative Council was formed and planned a peaceful march and rally to protest the forced use of Afrikaans in schools. Teachers agreed to support the rally because it was planned to be nonviolent.

On 16 June the students gathered, between 10 and 20,000 of them. Using different routes, they began to march toward the stadium bearing signs: “We do not want Afrikaans!” “To Hell with Afrikaans!” and “Afrikaans must be abolished!” When the students saw that police had put up barricades along the road, student leaders admonished them to remain non-violent and looked for new routes. They ended up at Orlando West School.

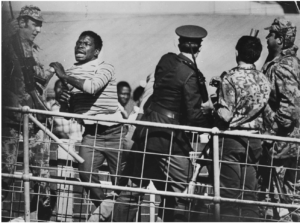

The situation deteriorated quickly. The police began by setting trained dogs on the students, who defended themselves and killed the dogs. The police reacted with bullets.

The first to die was 15-year-old Hastings Ndlovu. Then, later, 13-year-old Hector Pieterson was shot and the photograph of the aftermath of his death shocked the world and created an unstoppable international outcry that spelled the beginning of the end of the Apartheid era

“When the shooting began I went into hiding. When the shooting stopped, I came out of hiding when the others came out. I saw [my brother] Hector across the street and I called and waved at him. He came over and I spoke to him, but more shots rang out and I went into hiding again. I thought he followed me, but he did not come. I came out again and waited at the spot where I just saw him. He did not come. When Mbuyiso came past me a group of children were gathering nearby. He walked toward the group and picked up a body. And then I saw Hector’s shoes.” Antoinette Sithole

The photo of Mbuyiso carrying the tiny body of Hector Pieterson came to symbolize to the world what had happened in Soweto on 16 June 1976, but Hector served as a focal point in yet another way when, after a permit was denied for a mass burial of those killed in Soweto and the Apartheid government refused to release victims’ bodies to their families, Hector’s funeral was attended by thousands and use as a memorial for everyone.

But the ripples of what had taken place in Soweto were still not done. Rioting and peaceful protests alike spread throughout South Africa. On 17 June, as 1500 heavily-armed police invaded Soweto with the back up of armored personnel carriers and helicopters, more than 400 white students from the University of the Witwatersrand marched through central Johannesburg to show their support for the Soweto schoolchildren. They were joined by black workers from throughout the city.

In Kagiso a nonviolent student march ended with police killing five and retreating before being rescued by reserve forces, and the University of Zululand administration building and records building burned. The police forces demanded that hospitals and clinics report all gunshot wounds that were treated so that they could arrest the perpetrators of the uprising, but doctors and nurses refused to cooperate, instead listing gunshot wounds as “abcesses” in hospital records.

The black youth of Soweto took the most intense casualties, but the explosion of rage was not able to always distinguish between allies and enemies. In the official death count of 23 from the first day of rioting was included Dr. Melville Edelstein, the sociologist who had been warning about the rage simmering in the black youth from the unjust conditions created by the government.

Edelstein went to work in Soweto as he had for 18 years that morning, waving good morning to youth gathered outside his office. When news of the violence began to spread, he rushed back to his office from an official opening he had been officiating to make sure that a female colleague was able to get out safely. He shooed everyone out of the building, and when he was finally able to leave an enraged mob broke into the building and attacked him.

Edelstein was stoned to death, and when his body was discovered it was wearing a placard around its neck that said, “Beware Afrikaans is the most dangerous drug for our future.”

All this was occurring as the Apartheid government had been attempting to present a more benign version of their racist system to the world, and the state was never able to restore the white peace and social stability of the early 1970s. The rand quickly devalued in the face of the unrest, and even the United Nations was quick to condemn with Resolution 392, which condemned both the incident in Soweto and the apartheid government itself.

By the end of 1976, the violence had mostly ended. The official death toll was about 600 people, but the reality was most likely higher in Soweto alone. Thousands of the youth involved fled South Africa in order to avoid arrest and prosecution, ending up in military training camps for umKhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation), the militant arm of the ANC, in Angola and Mozambique. Later they would train in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union.

The Apartheid regime was still holding on, but its days were numbered. The world had seen the true face of South Africa’s policies, and it wore the face of a murdered child.

“It shook me to my core. I asked myself how this could be happening in our backyard while most of white South Africa just went on with their lives. Why didn’t they care?” Max du Preez, South African journalist.

From that moment on they would care.

- June 18, 2020

- South Africa