An Age of Peace and Prosperity

Od Kulina Bana i dobrijeh dana — Since Kulin Ban and the good old days

There has been enough upheaval in the history of Bosnia and Herzegovina that a saying about the best of times could be expected as a simile in any story (and if there is one thing Bosnia is full of it is stories). And, given the tensions that are often in the region, it’s probably not too surprising that the golden time period being referenced by all the BiH ethnic groups is approximately 900 years in the past.

Ban Kulin, who ruled Bosnia from 1180 to 1204 has remarkably sparse mention in the historical record. We don’t know what he looked like, when he was born, where he was born, or the total number of children he had. Until recent excavations under the ruins of St Nicholas Church outside Visoko we didn’t know where he was buried. We know he was married to Vojislava and had at least two sons, and we know he had a sister. We also know, although it is never stated outright, that he was possibly a Bogomil – a religious sect known as the Cathars in France and roundly denounced as heretics by the Catholic Church.

For someone with so few direct appearances in the historical record, it is more than a little surprising that the areas where Ban Kulin does appear, he does so in a huge way.

It is significant that an event that would define the rule of most men – breaking his nation out from under Byzantine rule – was probably the least significant event involving Ban Kulin in the historic record. It was important and it set the stage for the rest of his activities, but it is almost an afterthought in discussions about his later rule. In any case, Ban Kulin joined with the Serbian Grand Prince Stefan Nemanjić and fought under the Hungarian Empire to reject Balkan rule by the new Emperor of the Byzantine Empire in 1180.

The Byzantines were preoccupied with their own infighting, and so Ban Kulin was able to switch his allegiance to the Catholic Hungarian Empire without much trouble. In the process he was able to gain much more autonomy for Bosnia, as it was remote enough that the Hungarians couldn’t exercise much oversight.

That was, not much oversight until another Balkan ruler, Vuk Nemanjić of Zeta (now Montenegro) slyly mentioned to the Pope’s representative in 1199, “I can’t tell the difference between the heretics of Bosnia [the Bogomils] and true Christians!”

It was a calculated bit of tattle-taling on the part of Prince Vuk. In the middle ages one gained permission to invade and take over lands from another nation by questioning their commitment to the church. Vuk well knew that the members of the Bogomil cult, known as the Cathars in France and Italy, the Paulicians in Armenia, and often referred to as Manicheans in church writings, had been welcomed in Bosnia by Ban Kulin. He probably also knew that Ban Kulin himself, his wife, and his sister were adherents of the sect. All this religious upheaval presented quite the opportunity for a Grand Prince who could seize an opportunity, and Prince Vuk saw himself as that opportunistic Prince.

The Pope, primed by his times to jump into anti-Cathar crusades, acted immediately. He sent a letter to two papal legates: “A multitude of people in Bosnia are suspected of the damnable heresy of the Cathars!” he raged in his letter. The papal legates were to get to the bottom of the problem and to fix it by whatever means necessary.

With the power of hindsight and knowledge of what happened in most Catholic Inquisitions, it might be expected that a period of torture, holy war, and persecution was about to descend on the Banate of Bosnia. Ban Kulin, though, exercised an exhibition of diplomacy that would make any modern state Foreign Office gasp and clutch their pearls at the brilliance of audacity.

Ban Kulin didn’t argue. He didn’t fight. He invited the papal legates into Bosnia to have a look around and speak to whomever they felt they needed. He defended his actions at allowing the Cathars expelled from Split into Bosnia, calling them good Christians. And he offered to debate the papal legates about Catholic doctrine.

Actual records of his discussions with the legates no longer exist, but Ban Kulin must have been a tremendously persuasive speaker. Without bloodshed, torture, or a Rome-approved invasion by another nation, the Bosnian Church and Ban Kulin himself agreed to the demands of the legates. The Bilino Polje Abjuration was signed on 8 April 1203, and in it Kulin declared himself a strong and devoted Catholic.

Several other articles were included in the Abjuration – but most of them were of a very elementary nature. The monks in Bosnia had to renounce any schism and accept Rome as their mother church. Women had to be in separate religious quarters than men and could not speak privately with monks. Churches with altars and crosses needed to be erected, and these churches had to have at least seven masses per year said in them on holy days. Confessions had to be heard, the Catholic church schedule of fasts needed to be followed, and particular robes needed to be worn.

What was never mentioned in the entire treaty was a demand that the monks or Ban Kulin himself reject “heretical” teachings. Somehow, Kulin had effected diplomacy to such an extent that investigators who would become famous for their harsh treatment of suspected heretics in only a few short years not only left Bosnia without bloodshed, but left with only a signed admonition for Bosnians to behave.

Which the Bosnians, Ban Kulin first among them, promptly ignored. The Bogomils continued to be accepted in Bosnia and the Bosnian Catholic Church continued with their practices, growing in influence through the next two hundred years.

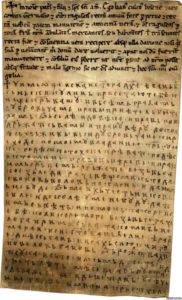

Ban Kulin is most famous, however, for his signature. In particular his signature on one document – The Charter of Ban Kulin. Written in 1189, the charter wasn’t ground-breaking at the time. It was merely written, signed, and sealed proof that citizens of Ragusa (present day Dubrovnik) were given the freedom to enter in and out of Bosnia at their will, conducting trade within the country as they chose.

What the charter means today is far more. It shows an existing Bosnian state that issued its own laws and conducted its own foreign policy in the twelfth century. It shows a thriving trade relationship between two entities who each recognized the sovereignty of the other. And it shows a diplomatic relationship in which a Bosnian leader was recognized as the head of a country named Bosnia.

The Charter of Ban Kulin is the oldest extant document from the Balkans, and it was written both in Latin and the unique alphabet of the Bosnian form of the Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian language. The alphabet, called Bosančici, was unique to the Banate of Bosnia, as both Serbia and Croatia had their own versions of scribing the regional language.

In effect, it is the historical proof of a medieval Bosnian nation; a nation that was led by a supremely talented diplomat-warrior – Ban Kulin.

Ban Kulin died in 1204, although nothing remains to explain why. He was succeeded by his son Stjepan and the beginnings of an independent and religiously tolerant Bosnian nation he had introduced continued on and moved forward for the next three hundred years.

- June 2, 2020

- Bosnia and Herzegovina