Franco-Serbian Tactics and Prussian-Ottoman Strategy in Kumanovo

By the Battle Of Kumanovo on 23 – 24 October 1912, the First Balkan War was young, but already in full swing – it would be a decisive victory for the Serbian forces, and a shattering loss for the Ottoman. Just a week prior, on 18 October 1912, King Peter I of Serbia had issued his declaration “To the Serbian People,” which called for a Holy War to free all Serb Christians and Albanian Muslims from the decaying totalitarian grip of the Ottoman Empire. It should be noted that the Young Turk Revolution in the Ottoman Empire had ushered in multi-party politics and electoral reform in 1908, effectively ending the constitutional monarchy and totalitarianism in Turkey, granting ethnic Turks a greater degree of freedom but creating a nebulous situation where those in outlying Ottoman territories could not be entirely certain what rules were in force.

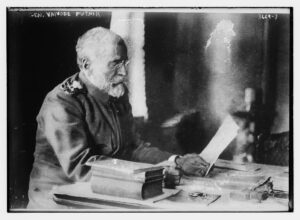

To be fair, King Peter I, of the Karadordević dynasty, was a libertarian, reformer, and stalwart military leader. He was born in 1844. Educated in Paris at the exclusive Saint-Cyr, the country’s most prestigious military academy, he excelled at a variety of intellectual pursuits, including publishing the first Serbian-language translation of John Stewart Mills On Liberty. King Peter I gained first-hand combat experience during his time with the French Foreign Legion, fighting in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870 as an officer. He won the Legion of Honor for fighting against the Prussians in the Second Battle of Orleans in 1870 and the Battle of Villersexel in 1871. He was captured by the Prussians, but escaped to return to France. Later, in 1875, King Peter I fought the Ottomans in in Northwestern Bosnia, commanding a unit of 200 Serb insurgents.

King Peter I’s reign, though brief, would be seen as a golden age for Serbia. The people would enjoy unheard of freedoms of the press, culture, and a burgeoning economy. But King Peter I came to power through a coup, and the murder of King Alexander I Obrenović in 1903, so none of the coming reforms would be self-evident until after the First Balkan War.

King Peter I chose Radmir Putnik to be Serbian Field Marshal and Chief of General Staff. An experienced officer born in 1847 from humble parents, Putnik had run afoul of King Alexander I, and was “rehabilitated” under King Peter I, and given command. Putnik was a professional soldier – an aesthetic who fiercely defended his point of view and demanded much from subordinate officers. Putnik had succeeded on the battlefield against the Ottomans before. In the numerous small wars between Serbia and the Ottomans in the late 1870’s, Putnik had won many battles and captured multiple cities for Serbia. Putnik had years to reorganize the Serbian Army to his liking, and did a splendid job with it. He promoted the senior officers, and he re-wrote the war plans. He was as prepared for war as a General could be.

The Ottomans took a different approach to their military. Their doctrine and strategy was written by Colmar Freiherr von der Goltz, or Goltz Pasha, as an entire Generation of Turkish Military Officers educated by Goltz, called him. Goltz was a contemporary of King Peter I and Putnik, being born in 1843 in Adlig Bielkenfeld, East Prussia. King Peter I and Goltz had fought on opposite sides as Lieutenants at Orleans, with Goltz in the Prussian Army, and King Peter I in the French Foreign Legion’s First Regiment. Ironically, despite being a Prussian, Goltz was a great admirer and student of the French Military. His books, written in German and translated into French and English, would be best sellers. His argument was that the French “People’s War,” a total mobilization of the populace against a foreign enemy, in this case Prussia, is what led the French to victory. His books became military classics even in the United States, where he was the predecessor to Carl von Clausewitz.

Goltz “People’s War” idea was simple – society must be militarized and mobilized during times of peace, so that it was prepared for total war. It was mass Social Darwinism, a call to brutal ultra-nationalism, and for strong nations to devour weak ones. War was the highest calling of men, and “Perpetual peace means perpetual death.”

After the Ottoman defeat in the Russo-Turkish War in 1878, the Ottomans requested Prussian assistance in reorganizing their defeated military. Goltz answered the call, and educated a generation of Ottoman Officers, the Goltz generation,” who would later take high-level positions in the Ottoman military and government. His approach melded perfectly with the Ottoman view of life, and he spoke fluent Turkish. At the end of his service, Goltz received the Pasha title, which was unheard of for a non-Muslim. And at first, Goltz approach worked. The Ottomans experienced smashing success in the Greco-Turkish War of 1897, only stopping when the Russian government threatened to open a second front.

Although long returned to Europe by the time the Young Turk Revolution broke out in 1908, Goltz had nothing but praise for his former pupils, who dominated the government. Goltz stayed an advocate of Muslim Turkey against the Christian nations of the Balkans, even into the sectarian Balkan Wars that overtook the region. In a worrisome foreshadowing of the horrifying wars to come, after retirement in 1911, immediately before the breakout of the First Balkan War, Goltz founded the Jundeutschlandbund, an umbrella organization for right wing German youth.

The battle of Kumanovo would pit Putnik’s tactical and strategic reforms of his professional army against the People’s War theory of Goltz. The Serbs started the war, hoping to use the battle to destroy the Ottoman army before it had a chance to gather and build strength. Goltz had cautioned that the Ottomans must build critical mass, and should fight defensively until they were capable of doing so. Goltz even counseled retreat from Macedonia into Albania if necessary to fight in terrain where the Ottomans had the advantage.

The Ottoman Chief of Staff during Kumanovo was Nazim Pasha, another graduate of the French Saint-Cyr military academy in Paris, who had been born in 1848. He was a contemporary of King Peter I, and might have been a classmate, although it is known if the two ever met at Saint-Cyr. Nazim might have believed in Goltz philosophical teachings, but his adherence to the doctrine slayed out by the philosophy violated the teachings. Believing his Ottoman units to be superior in training and leadership, Nazim went on the offensive against the Serbian Army, commanded by Putnik and King Peter I. Nazim also had good intelligence about the location and disposition of the Serbs, as well as enjoying superiority in artillery and machine guns. Nazim’s field commander on the ground at Kumanovo was Zeki Pasha, a competent, but unimaginative officer who had previously specialized in massacring Armenian civilians during insurgencies such as at Sassoun in 1894.

Skirmishes happened in the days leading up to the Battle of Kumonovo. Chetniks, Serbian paramilitaries who had not yet become associated with fascism but were just royalist supporting forces, launched an attack across the border from Serbia into Ottoman territory near Pristina. They were beaten back by the Ottoman counterattack, but soon the Balkan regular military forces pushed the Ottomans back toward Kumonovo, capturing Pristina themselves.

The battles lines north of Kumonovo were laid out with the Balkan forces coming from the north, and the Ottomans defending to the south. The majority of the heavy fighting took place on 23 October 1912, directly east of the city, with Ottoman forces supported with superior artillery. Ottoman forces understood the strong and weak points of the Serbian defenses, but the Ottomans soon outran their artillery, and the Serb artillery stopped their advance. The majority fo the Balkan forces was held in reserve, while the Ottomans committed a majority of their forces in an attempt to shatter the Balkan armies.

The next day, 24 October 1912, went worse for the Ottomans. The Balkan troops advanced across the entire front line. On the west side of the battlefield, which had been quiet the previous day since the fighting had been on the east, the Ottoman reservists defending the flank finally received the news that Pristina had fallen to the Serbs, and deserted. The Ottomans were sorely outnumbered by the Serb forces, but Zeki launched an attack anyway. This predictably failed, with the collapse of the Ottoman left flank causing an overall Ottoman route. By 1500 that day, Serbian forces entered Kumonovo and the battle was over. The fleeing Ottoman army was forced to abandon a 100 of its artillery pieces. In the end, Serbian deaths were significantly less than the Ottomans, with approximately 700 dead, compared to the 1,200 the Ottomans lost. However, total casualties, including wounded and captured were approximately 7,000 on each side.

The Ottoman Army couldn’t absorb such casualties and was forced to continue its retreat out of the Balkans. Balkan forces cut supply lines, further reducing the Ottoman artillery advantage, and harassed Ottoman units, pushing them out of Skopje, another major city in the region.

The fates of the men involved didn’t match their armies. Goltz was recalled from retirement into the Army in World War I by the German Army. He became the Military Governor of Occupied Belgium, and ordered a number of atrocities against the Belgian civilian population. After the horrors of that war, he returned to Ottoman service, fighting against the Germans and dying of Typhus in Baghdad on 19 April 1916.

Putnik would see the Serbian army outclassed and outnumbered by the Austrian/German/Bulgarian coalition in WWI. He fought bravely and brilliantly, but was forced to retreat from the country and see it fall to Austria. He was fired by the Serbian Government in January 1916 and humiliated by finding out about his dismissal from a pay clerk. He exiled himself to France, where he was greeted with honors. He died there on 17 May 1917.

King Peter I would retreat from Serbia with Putnik into exile on Corfu in November 1915. After the war he returned to Belgrade where he was crowned King of Serbs, Croates, and Slovenes on 1 December 1919. He abdicated in favor of his son in 1919 and died peacefully in Belgrade on 16 August 1921.

Nazim was assassinated on 23 January 1913 by Young Turk rebels during an Ottoman coup d’etat. His disastrous campaign plan would doom the Ottomans in the Balkans, but he was killed for allegiance to the wrong political group.

Instead of being punished, Zeki, the true force behind the Ottoman failure at Kumonovo was given diplomatic positions with the Central powers. Zeki negotiated his way through the coup that killed Nazim, and in a supreme irony, Zeki rose to become the Ottoman Chief of General Staff in 1920. He retired peacefully in 1923.

- October 9, 2020

- Serbia