Alexander’s Rome

Cleopatra VII Philopater, mistress of Julius Caesar, wife of Marc Antony, Pharaoh of Egypt, killed herself on 12 August 30 BC. With her death the Ptolemaic Dynasty of Egypt ended.

Except, actually, it didn’t.

Cleopatra was, genetically, Egyptian-in-name-only. The Ptolemaic Dynasty came to power in Egypt after the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC. Nor were the Macedonian Ptolemies, whose birth language was Greek, the first Pharaohs from the outside. There was considerable back-and-forth between the native Egyptians and the Persians from 525 BC. When Alexander the Great finally came along and was basically gifted the province in 332 BC by the last Pharaoh of the 31st Dynasty, there had been several decades of sole Persian rule.

Alexander, as we all know with hindsight, wasn’t much longer for the world after the Egyptian conquest. He headed out for more war, but never returned alive. He did have a cadre of beloved and close male friends with him, though; one of whom was a man named Ptolemy.

Ptolemy grew up and was educated along with Alexander. Most likely, he and Alexander were also half-brothers – Ptolemy’s mother Arsinoe had been Phillip II of Macedonia’s mistress and was married off to her husband Lagus when already pregnant. Of course, this possible relation could have been a cynical ploy to make the family bloodline look fancy, but enough contemporary chroniclers mention the connection that it is more than a distinct possibility.

It was Ptolemy who pushed for the deal that created a regency for the soon-to-be-born Alexander IV with Perdiccus as regent. But Ptolemy didn’t stop with arranging the fate of the Macedonian kingdom. Macedonian custom stated that the new king would bury the old king. Alexander had requested to be buried at the Temple of Zeus Ammon in what is now Libya, but the regent Perdiccus was transporting his body back to the royal tomb in Macedonia. Ptolemy, with great effort, managed to gain control of Alexander the Great’s body and attend to the conqueror’s burial himself; first in Memphis, then in Alexandria. It was a powerful statement, and hard to ignore. All the more so because Ptolemy then joined the rebellion against the regent Perdiccus.

In 321 Perdiccus attempted to address the rebellion by provoking a battle on the Nile. He lost. Perdiccus didn’t only lose, but managed to get himself killed by two of his men. Ptolemy was simply the better general.

He was also the better leader. Upon his victory, he offered the Macedonian army food. The army responded by offering him the regency, in effect, the rule of the entire Macedonian Empire.

And this is where Ptolemy sets himself apart from nearly every self-made ruler who has ever pulled himself up by his not-quite-royal bootstraps: he said no.

Known, in addition to his battlefield prowess, as fairly good natured and liberal minded, Ptolemy also strove for good relations with the natives of areas he ruled. And he spent the next decade as the Satrap (governor) of Egypt for Alexander IV, although in truth he was really ruling independently. When Alexander IV and his mother Roxana were poisoned by the regent Cassander the situation completely changed. Soon after, in 305 BC, Ptolemy proclaimed himself Pharaoh of Egypt, under the name Ptolemy I Soter (Soter means “savior”, for anyone thinking that Ptolemy must have been a really humble kind of guy. He probably wasn’t).

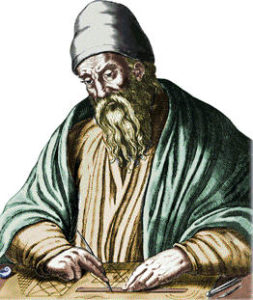

And, with the majority of his conquering and squabbling done, Ptolemy settled down to write a first-hand history of Alexander’s conquests, which sadly does not survive but does show that he still carried a torch of bromance for his half-brother and the glory days. He also founded the famous Library of Alexandria and even personally sponsored the mathematician Euclid.

With Ptolemy I, the Ptolemaic Dynasty was born. Ruling males all carried the name Ptolemy. They often co-ruled with their Queens, and some Ptolemaic Queens even ruled on their own, carrying over a remarkable nod toward equality which carried over from the surprisingly feminist Philip II and Alexander the Great.

Ruling queens all carried the names Arsinoe, Cleopatra, or Berenice.

The Ptolemies made some nods toward local culture: they supported the Egyptian religion and latched onto the custom of in-breeding, marrying their siblings with distressing regularity. They also appeared in public monuments wearing Egyptian dress and style. But they maintained Macedonian customs in government bureaucracy and Greek as the language of the government until the Islamic conquest in 641. In fact – the first Ptolemaic Pharaoh to speak Egyptian was the last Pharaoh, Cleopatra VII.

The Ptolemies also brought in a large number of Macedonian soldiers, rewarding them with Egyptian lands to settle on. This created a large Greco-Egyptian educated upper class and a layer between the ruling Ptolemies and the rest of Egypt.

In 51 BCE 231 years had passed since Ptolemy I Soter’s death, and Cleopatra VII Philopater came to power as the wife of her brother Ptolemy XIII. After he was killed in battle against Julius Caesar, Cleopatra became co-ruler with another brother, Ptolemy XIV.

That Ptolemy was killed, too.

Countless movies and books have portrayed the rest: Cleopatra’s affair and child with Julius Caesar, her affair and marriage with Marc Antony, their suicide. Whether Cleopatra is portrayed as cruel and domineering or wily and astute, they all portray her as strong. There can be little doubt that trait carried down in her DNA and family culture from the Ptolemaic Macedonian origins.

But, contrary to popular history, everything didn’t end when Cleopatra encountered the fateful asp.

There were four royal Ptolemaic children, and one was a daughter – Cleopatra Selene. Cleopatra Selene was raised by Octavia the Younger, her father’s ex-wife. And not just any ex-wife, but the wife he left to go live a life of hedonistic luxury in Egypt with Cleopatra Selene’s mother.

Cleopatra Selene married well – Juba II, the King of Mauretania. Their son, Ptolemy of Mauretania, was a dead ringer for his grandfather, Marc Antony. And through her granddaughter Drusilla, the circle would close. Drusilla’s descendants would marry into the Roman nobility, starting with the Emperor Septimius Severus.

The royal line of Macedonia, which would conquer the civilized world in the fourth century BCE, would become a part of ruling the Roman Empire.

- August 4, 2020

- Macedonia