The End of Slavery on the Island

At break of day a signal of three smacks of a whip called them to work, when each betook himself with his spade to the plantation, where they worked almost naked in the heat of the sun. Their food was bruised or boiled maize or bread made of cassava root, their clothing a single piece of linen. Upon the commission of the most trivial offense, they were tied hands and feet to a ladder, where the overseer approached with a whip like a postilion’s and gave them fifty, one hundred, and perhaps two hundred lashes upon the back. Each stroke carried off a portion of skin. — Jacques-Henri Bernardin de St Pierre

The empty island that would be called Mauritius had its first crack at settlement in 1638, when the Dutch attempted a colony on the island that included African and Indonesian slaves. Conditions were harsh for everyone, but the slaves received the worst of everything. As a result, many slaves ran away and hid in the forests, joined by dissolute workers in launching raids on the Dutch possessions.

By 1710 the Dutch had had enough and the last of the settlers, barring those who chose to remain hiding in the forests, were evacuated. The island remained dormant again until 1721, when the first French settlers began to arrive from Reunion Island.

The French settlers changed the name of the island to Ile de France, but they did not change a reliance on slavery. In fact, as the sugar market became more lucrative the import of slaves increased and was officially sanctioned in 1723. In 1767 when the French purchased the island from the French East India Company there were 18,777 people (15,000 of them slaves) on the island. By the end of the 1700s more than 160,000 slaves had been imported to Mauritius and Reunion, most of them from Africa, but 13% of them originated from India.

Slaves and free blacks in Mauritius were subject to the Code Noir, which laid out the rules and responsibilities of slavery and slave owners. Broadly, the Code Noir regulated the treatment of slaves, who would be considered slaves, the punishment of slaves, restricted the activities of black people in general, and made the Roman Catholic religion compulsory for all who were enslaved.

“There was a law in force in their favor called the Code Noir or the Black Code, which ordained that they should receive no more than 30 lashes for any offense, that they should not work on Sundays, that they should eat meat at least once per week, and have a new shirt every year; but this was not observed,” said Jacques-Henri Bernardin de St Pierre.

In fact, when the Revolutionary Government of France banned all slavery in all French possessions, the Mauritian plantation owners just ignored the order.

On 3 December 1810 the island again changed hands, this time falling to a British invasion. The British reverted the island to the name Mauritius, and it became subject to the increasing antipathy of the British public to the institution of slavery.

Plantation owners saw the writing on the wall. Knowing that slavery was on its way to being abolished, and in a way that they could not ignore as with previous French edicts, the plantation owners began to import Chinese and Indian indentured servants who worked alongside the slaves in the sugar cane fields.

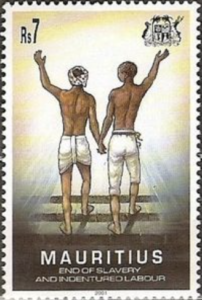

On 12 June 1833, the British Parliament passed a law abolishing slavery. Dragging its feet, the leaders of Mauritius finally came up with a plan in January 1835 that allowed for four years of apprenticeship for slaves, and upon emancipation slave owners would be compensated for their loss of property. Slaves themselves were not given compensation, although they were supposed to receive training in job skills. This did not happen on a large scale, and most ex-slaves entered freedom in abject poverty. When the date of freedom arrived in 1839, Mauritius’s population numbered 9,000 whites, 15,000 free coloureds, and about 70,000 slaves.

The population of Mauritius was about to undergo another massive shift, however, as boatloads of Indian laborers arrived to fulfill the need for hard labor in the sugar fields. Within twenty years, Mauritius held 193,000 people of Indian origin and 117,000 whites and coloureds.

The influx of Indian labor continued until 1909, although the final shipment of workers arrived during a short sugar boom in the 1920s. Indian workers were subject to extreme abuse that was little better than slavery, but by the beginning of the twentieth century they had managed to purchase 1/3 of the cultivated land on Mauritius.

Mauritian slavery was not confined to the island of Mauritius, however. On 27 October 1808 a slave revolt took place in Cape Town, South Africa. The leader was a Mauritian slave named Louis. The rebellion was short lived and Louis was sentenced to death, but the Mauritian legacy of escaped and rebelling slaves continued on, even away from the island.

For more on the history of slavery, please click here.

- February 1, 2021

- History , Interesting