Past Is Prologue

In the end, the man who spent nine years denouncing colleagues in the Soviet Union, leading to hundreds of interrogations and at least 15 executions, was executed himself.

It creates an interesting juxtaposition – the Imre Nagy of before the Hungarian Revolution of 1956, and the Imre Nagy to led the short-lived government of the Revolution and was summarily kidnapped and executed for doing so.

Nagy was certainly no coward. Inducted into the Austro-Hungarian army at the start of World War I, he was wounded at the 3rd Battle of Isonzo. In 1916 he was sent to the Eastern Front, where he was wounded again, taken prisoner by the Russians, and sent to Siberia.

Mirroring the experience of several others, including Tito of Yugoslavia, it was while he was a POW in Russia that Nagy converted to the communist cause. He even fought with the Red Army before being captured by Czechs, from whom he escaped and lived a semi-underground life in Russia until 1920.

Nagy spent 1920 as a clerk for the Cheka, digging into the cases of POWs. They also trained him in subversive activities. By 1921 he was returned to Hungary to set up underground communist networks where the communist party was banned.

He didn’t do terribly well in that role, and was arrested by the Hungarians in 1927 and imprisoned for two months. He worked as an insurance agent while attempting to bring together communist sympathizers and convert others to the cause.

Eventually, though, Imre Nagy returned to the Soviet Union in 1930. There, he regained his membership in the Communist Party and became a Soviet citizen. It was also when, under the code-name Volodya, he took up the practice of reporting on his work fellows and keeping the NKVD supplied with people to execute.

Nagy returned to Hungary after World War II, serving in various government roles including the Minister of Agriculture and the Minister of Interior. While Minister of Interior he participated in the brutal relocations of the ethnic Germans in Hungary. He also signed the note ordering the arrest of Janos Kadar in 1951, which led to Kadar’s show trial and torture. Given what would occur just five years later between Nagy and Kadar, it’s an interesting point to consider whether that had any bearing on Kadar’s role in Nagy’s own arrest.

The Soviet Presidium attempted a short-term reformation of some of the Rakosi government’s more problematic issues between 1953 and 1955; and to that effect they appointed Imre Nagy Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Hungarian People’s Republic, but Rakosi was having none of it. He undermined Nagy at every chance, and on 18 April 1955 Nagy was sacked and removed from the party.

If Imre Nagy had been anything his entire adult life, he had been a committed communist who didn’t stint at demanding punishment for those who strayed from the party line. As such, it was probably the fact that Nagy was hated by Matyas Rakosi and the restive population itself hated Rakosi that made them look toward Nagy as his replacement. Nagy was not really a reformer, and even when his name was included as a demand by the protesting students’ Sixteen Points, Nagy still believed the students were too radical in their demands. In fact, on his first address to the crowds of protestors he was booed when he opened his speech by referring to them as “comrades”.

But from there events moved quickly. By 24 October the Soviets re-appointed him Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Hungarian People’s Republic to appease the protesting students. By 28 October he was negotiating a cease-fire with the Soviet Army and reorganizing the Hungarian government. By 30 October he was announcing changes to the Marxist system in Hungary, referring to the “rigid dogmatism” of “the Stalinist monopoly” and appointing non-communists to the government. On 1 November he announced Hungary as a neutral country that was withdrawing from the Warsaw Pact. And by 4 November it was over – he was granted asylum in the Yugoslav Embassy as the Red Army he had once fought with re-entered Budapest and seized the country back from its nascent revolution.

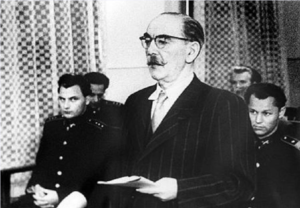

There were still a few vignettes left: on 22 November Nagy, his family, and other members of his government were kidnapped and taken to Romania. On 16 June 1958 he was hanged, in Khrushchev’s words, “as a lesson to leaders in other socialist countries.”

First buried in an unmarked grave in the yard of the Budapest building reserved for political executions, Nagy was later moved to another site and buried, wrapped in tar paper and with his hands and feet bound with barbed wire, under a false name.

In 1989 he was given a hero’s funeral and a proper memorial, but his statue and memory are still provoking controversy today.

“What I betrayed was not the ideal, but the system which betrayed the ideal,” Imre Nagy, in his confession.

For more in our ongoing series about the Hungarian Revolution, click here.

- November 25, 2020

- History