The Devil in the Details and the Kingdom

There was a slaughter.

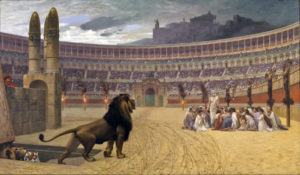

From 303 a series of edicts from the Roman government rescinded the rights of Christians in the Empire and demanded that everyone sacrifice to the gods. Those that didn’t conform were killed – although this was enforced to different levels in different places. Illyricum and Thrace, the Balkan areas of the Empire, enforced the edicts most strenuously. The Emperor who set the persecution ball rolling was Diocletian, so it was his name that was attached for eternity to the last great attempted purge of Christianity in the Roman Empire.

The Diocletian Persecution began in 299 with haruspices at a royal palace in Antioch attempting to read the future in animal entrails and feeling as though they were blocked from doing so. The head haruspex claimed that the ceremony had been tainted by some who profaned it by making the sign of the cross, and by the presence of Christians in the area in general. The Haruspex had said exactly what Diocletian needed to hear and got exactly the reaction he was looking for. Diocletian was enraged. Egged on by the future Augustus Galerius, all members of the household and the army were ordered to make sacrifices or face expulsion. But the blood had not yet begun to run in the streets.

The leading pagans in the Empire, the devout Galerius among them, were still worried, and so the persecution began to spread.In 302, a much smaller Gnostic offshoot sect of Christianity, the Manichaens. After orders to sacrifice to the gods were refused in 302, Diocletian ordered the leaders of the movement burned alive with their scriptures. Later, rage unabated, further orders to behead the lower class members of the sect and enslave the upper class members to work the quarries followed.

Finally, in 303, the mass eruption of anti-Christian feeling came to the surface when a Christian Deacon named Romanus interrupted a ceremony of sacrifices to denounce the proceedings. The fear and hatred of the rapidly growing religion erupted to the surface. Romanus, who was later sainted, had his tongue cut out and was thrown into a dungeon. Eventually, after the Fourth Edict of 304 was issued, Romanus was killed.

The Fourth Edict of 304 was issued in February. By March everyone in the Balkans knew that they had been ordered to give sacrifices in the public square or face death. As in past persecutions, some Christians submitted and participated, but many more refused. In Singidunum, the modern Serbian city of Belgrade, Christians began to flee as the persecution began. The Priest Montanus and his wife Maxima were among those fleeing, but were captured in Sirmium (now Sremska Mitrovica) in 304. Montanus and Maxima faced trial and continued to eloquently refuse to sacrifice.

They, like many other Christians, were beheaded and thrown into the Sava River. Long lists of Christian victims were killed, including Iraenaeus, the Bishop of Sirmium. Even the pagans of the Empire began to protest this treatment. The Diocletian Persecution began to wind down starting in 305. Galerius himself issued the Edict of Toleration in Serdica (now Sofia, Bulgaria) in 311, but persecutions carried on in other areas until 313.

The Diocletian Persecution was a catastrophe for Balkan Christians, so it is no wonder the name of Diocletian himself was spoken with hatred, disgust, and fear. Through the years, the name also began to evolve. Within 200 years, Hun, Avar, and Slav invasions began to change the character of the inhabitants of the Balkans and a Slavic language would emerge to replace the Latin of the Roman Empire. The name Diocletian, not easily rendered into Slavic, would become Dukljan. And in Serbia, Dukljan would become the name of the Devil.

Dukljan the Devil

In a Serbian folk song, Dukljan managed to remove the sun from the sky, but he was unable to keep it. Tricked by Saint John, Dukljan returned the sun to the sky. However, as Dukljan chased the saint he was able to rip a piece from his foot. This is the uniquely Serbian story to explain how humans developed arches (and rather recently, too).

Dukljan was not just allowed to run amok amongst honest and God-fearing people, however. According to the stories he is still chained today in the Morača River near the town of Duklja. He constantly gnaws at his chains and manages to escape every year near Christmas. Luckily there are four Roma blacksmiths who are dedicated to recapturing him and reforging his chains, keeping Dukljan from wreaking havoc in the world. It is possible, though, that the Roma blacksmiths were otherwise occupied around Christmas of 2019, and 2020 might be the work of a newly freed and rampaging Dukljan. It’s probably as good an explanation as anything else.

Duklja the Christian Kingdom

Diocletian, however, did not only loan his name to the Balkan devil. Like most Roman Emperors, he was terribly short on naming inspiration: baths, cities – whatever Diocletian touched bore his name, including a town just north of what would become Podgorica, the capital of Montenegro. The town was called “Doclea.” Just as Diocletian became slavified into Dukljan, Doclea also became Duklja. And Duklja would lend its name to a kingdom that would break away from the Byzantines and eventually be ruled by Mihailo Vojislavović, a man the Pope would declare “King of the Slavs”.

As with many places in the Balkans, the time between the end of Roman rule in the Duklja area and the emergence of a medieval kingdom has sparse evidence to examine. The Huns began invasions in the 520s, followed by the Avars. After these raids had greatly depopulated the area the Slavs moved in, razed most of the remainders of Roman civilization, and spread their language and culture. By 580 the areas of the Balkans now under Slav control were referred to as “Sclavinia”, although Avar raids would continue well through the 600s in the Duklja area.

The people who lived in the kingdom, though did not call their nation Duklja. Although the city was still referred to as Dioclea, by 1080 all papers referred to the kingdom as “Zeta”, the name that would be used until it was replaced by “Montenegro”. The name Duklja was first used to describe the nation in the 1800s by the Czech historian and Slavist Konstantin Josef Jireček, and the name managed to stick.

The city Dioclea was referred to in the tenth and eleventh centuries, and by 1034 Dukljan’s leader, Stefan Vojislav, was described as “the leader of Serbs who renounced Byzantine rule” by the contemporary Greek historian John Scylitzes. After much skirmishing, the rebels managed to gain their freedom, and the height of what we call the Kingdom of Dukljan would be between 1050 and 1101 before it descended into in-fighting and was absorbed by the Principality of Serbia.

The most famous time period of the Kingdom of Dukljan was not its Golden Age, however. It was the rule of the Prince (and later Saint) Jovan Vladimir. Thanks to the thirty-sixth chapter of a manuscript called The Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja, a hagiography of the rule of Prince Vladimir exists. The actual historical value of the recounted record is viewed as completely inaccurate, but as it is believed to have been written in the 13 Century, it gives valuable insight into how people of the period immediately after the Duklja State existed remembered their history.

Prince Jovan Vladimir ruled the principality between 990 and 1016, a time period when Bulgaria and the Byzantines were engaged in vicious fighting. Vladimir was a Byzantine vassal, but he was taken prisoner by the Bulgarian Tsar Samuel.

The Chronicle romanticizes Vladimir to the extreme, and although the historical record does state that he and Kosara, the daughter of Tsar Samuel were married, it puts quite a romantic spin on the event:

“It came to pass that Samuel’s daughter Cossara was animated and inspired by a beautific soul. She approached her father and begged that she might go down with her maids and wash the heads and feet of the chained captives. Her father granted her wish, so she descended and carried out her good work. Noticing Vladimir among the prisoners, she was struck by his handsome appearance, his humility, gentleness, and modesty, and the fact that he was full of wisdom and knowledge of the Lord. She stopped to talk to him, and to her his speech seemed sweeter than honey and honeycomb.”

Most likely, Tsar Samuel saw a chance to keep the Prince loyal to Bulgaria after his release, a common contractual reason for noble marriages at this time, but either way the marriage was quite successful. Vladimir and Kosara returned to Duklja, and although he was allied with the Bulgarians, he was not required to take part in the ongoing war.

Although The Chronicle again idealizes the union between Vladimir and Kosara as saintly, reporting that they lived in chastity, the fact that they had a daughter who would go on to marry Stefan Vojislav makes that claim highly unlikely. Their marriage does seem to have been very successful, though, and Kosara’s behavior after Vladimir’s death shows an extreme degree of devotion.

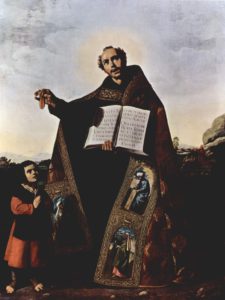

In 1016 Samuel was no longer Tsar of Bulgaria, and Vladimir was summoned to the town of Prespa to meet with Tsar Ivan Vladislav. Ivan Vladislav even sent Vladimir a token of safe conduct – an ornate golden cross.

The cross meant nothing to Ivan Vladislav, however. With little fanfare he beheaded Vladimir as Vladimir exited the church in Prespa from prayer. The reason for executing Vladimir is not entirely clear – it’s possible that Vladimir might have been planning a return to the Byzantine Empire; no one knows for sure.

We do know that his wife Kosara never remarried, however. She was instrumental in getting Vladimir’s remains moved from the church where he was murdered and moved nearer to where he had held court, in the church at Prečista Krajinska. When she died she was buried at his feet.

A Final Reckoning

Vladimir became Saint Jovan Vladimir, and is regarded as the first Serbian saint. His remains were moved twice more, and are now housed at the Orthodox Cathedral in Tirana, Albania. Hist story is far from over, however. Both Christians and Muslims attend the Cathedral on the saint’s feast day, and stories of both Christians and Muslims being cured after offering prayers at the saint’s reliquary.

The cross that St Jovan Vladimir carried when he was executed has been in the care of the Andrović family of Montenegro for several hundred years. It is brought out once a year on Pentecost and carried to the summit of Mount Rumija in Montenegro. The ceremony is attended by Orthodox and Muslims, who walk behind the cross, carried by an Andrović family member. In the past a member of the Muslim Mrkojevići family would walk next to them as a standard bearer, the flag in his left hand and a knife in his right, to prevent anyone from stealing the relic.

Over one thousand years after Prince Jovan Vladimir ruled a principality that came to be known by one of the nicknames of the devil, his remains are a uniting and healing presence between two cultures in a region often overcome with religious friction. The Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja might be a hagiography, but given what Saint Jovan Vladimir has been able to accomplish in death, maybe it was a hagiography he deserved.

- July 10, 2020

- Montenegro , Serbia