Eighty Years to Change the World

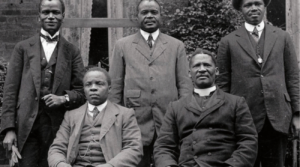

On 8 January 1912 in an unprepossessing Wesleyan Church in the Black community of Waaihoek near Bloemfontein several men and one women met to create the organization that would shake the foundations of the South African nation.

The South African Native National Congress would become the African National Congress eleven years later in 1923, but the name change did not reflect movement away from the men and the woman who founded the organization, meant to combine native movements across the nation into one powerful movement capable of stronger protest and representation.

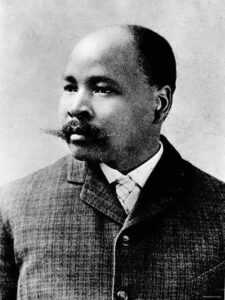

The first president of the organization, John Langalibalele Dube, served as president for five years. He was educated in the United States and throughout his life advocated two main ideas: the need for human rights and the need for Africans to stand together. Dube was one of the first Zulu authors \to write about Zulu history.

He was joined by Sol Plaatje, a polyglot author and the first black African novelist in English, Josiah Gumede, the first black African lawyer in South Africa – Pixley ka Isaka Seme, and the first black African woman to graduate with a university degree in South Africa – Charlotte Maxeke. The founders were highly educated, forces of education for other Africans, and extremely motivated to better their nations – Plaatje translated works of Shakespeare into the Tswana language, while Dube and his wife founded the first Zulu/English newspaper.

The basis for the organization was provided in a 1911 statement by Pixley ka Isaka Seme, “Forget all past differences among Africans and unite in one national organization.“

It was no coincidence that the meeting occurred at a church in a black African community – the locality of Waaihoek had specifically been created for the servants of white families who lived in Bloemfontein. To the disgust, anger, and horror of the leaders of the native movement, “pass laws” instituted in 1891 applied to all non-whites in the area, and police were given the power to demand passes from everyone. As a result, women often found themselves set upon as their pockets were rummaged through and they were detained at the pleasure of the law enforcement officers and subjected to disrespectful behavior and abuse. The requirement for a pass, which often had compulsory renewal every month at a cost high for the average domestic laborer, was humiliating enough. But the information on the pass was even more invasive: it included the official employer, official residence, reported wages, reported tax payments, and years in service.

Non-whites in South Africa were not only harassed through legal and extra-legal means, they were also kept in perpetual poverty by the taxes and fees required just to go about daily life. The legal harassment served a double purpose – to force them to comply with petty rules on a constant basis with little room to protest, and to create a constant feeling of degradation that continually reminded non-whites they were the lowest figures in the social order.

The men and the woman who founded the SANNC/ANC in 1912 meant to end these practices.

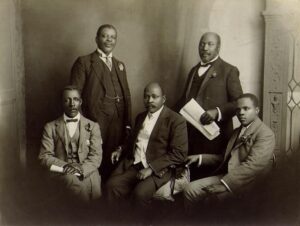

This was not the first organization to rise out of pass laws and denial of voting rights; in 1909 many of the same men met in the South African Native Convention, which then sent a nine-man delegation to Great Britain in an attempt to force changes and better the position of native black Africans. The delegation received sympathetic coverage in the British press, but little else came of it.

Within a year of the founding of the SANNC/ANC, Bloemfontein would see mass demonstrations of women protesting the passbook laws. Led by Charlotte Maxeke, these protests began on 28 May 1913 with marches and women tearing up their passbooks in front of municipal buildings. Solidarity marches were held in other cities, some of which were attended by white women wishing to demonstration support for the movement. Blue rosettes began to appear on supporter’s clothing, across the lines of skin color.

Although there was movement in some areas, the developing apartheid system in South Africa continued moving forward.

On 12 July 1918 “The Waaihoek Tea Party” provoked a heated argument for several months in the founding community of the SANNC/ANC. A non-white resident of Waaihoek had applied for a permit to hold a tea party in his own home, and the permit was granted. The tea party went over the allotted time by 45 minutes, however, and the local resident was sentenced by the magistrate to a one pound fine or two weeks at hard labor.

The local Anglican deacon, Frank Howell Hulme, protested against the absurdity of this sentence in the local newspaper, and pointing out that it was blatant “discrimination against black people.”

Arguments rang in the paper for months, descending into recriminations and name-calling amongst the white population. It was this rancor that finally caused a halt in the public discussion and left, unfortunately, nothing changed for the better for the black South African population.

It would take until 1994 and the creation of a new South African government for the dreams of the founders of the SANNC/ANC to be realized, but the spark that created the Rainbow Nation was started in an unprepossessing church in a black African community on 8 January 1912.

To learn more about South African culture and history, click here.

- December 14, 2020

- South Africa