The People Are Not Fighting For Ideas

Always bear in mind that the people are not fighting for ideas, for the things in anyone’s head. They are fighting to win material benefits, to live better and in peace, to see their lives go forward to guarantee the future of their children.

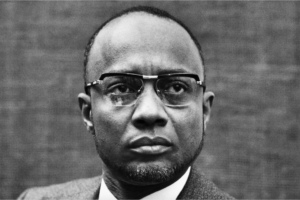

When Amilcar Cabral was shot by his own men on 20 January 1973, he had already set in motion the movement that would remove the yoke of colonialism from Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde. At that point in time he had already led the fighting that had liberated a significant amount of Guinea-Bissau out from Portuguese control and was the de-fact leader of the majority of the country’s area. Indeed, it was quite possibly his success that made him a target. Although recently declassified documents from the United States found that, less than a month after his assassination, that the Portuguese had not been involved, the US State Department was not so quick to let the Estado Novo dictatorship in Portugal off the hook, and stated that Portuguese involvement could not be ruled out.

None of the leading conspiracy theories have been proven, but it is certainly nothing new for internal revolutionary power struggles to erupt in the assassination and murder of rivals. One popular theory is that Ahmed Sekou Toure had Cabral killed by Inocencio Kane in Conakry in response to Cabral’s greater international prestige. With the death of Cabral, Toure was also seen as leading the Pan-African movement.

Another theory should also receive significant attention – the possibility that Portuguese authorities wished to neutralize Cabral by arresting him and holding him under Portuguese authority. This theory is somewhat supported by reports that Inocencio Kane reportedly attempted to arrest Cabral before Cabral’s refusal to comply led to his assassination.

The truth is that Amilcar Cabral had a great many supporters and a great many enemies, and that his personal charisma, education, and new ideas about revolution brought him into conflict with people on all ends of the political spectrum. Just about any faction involved in the independence movements of the mid-20th Century had someone and/or some reason to want him removed.

When Cabral was born in 1924, his parents were on opposite ends of the social spectrum. His father was a member of a landholding family, while his mother was a shopkeeper whose family could not afford to have her educated. But Cabral was educated, and his education was well-rounded. Vastly influenced by the Claridade movement of Cape Verdean literature and poetry, Cabral wrote prose and poetry himself. His scholarly efforts did not go unnoticed – the Portuguese colonial government saw his potential as an “assimilado”, a colonized African considered sufficiently “civilized” to be “assimilated” into Portuguese society, and Cabral was sent to study at university in Lisbon.

It was in Portugal, while studying for an advanced degree in Agronomy, that he came in contact with the anti-colonial and Pan African movements that would define the rest of his life. He began organizing while in Lisbon, founding a student movement opposing the Portuguese dictatorship and promoting the independence of the African colonies.

When Cabral completed his studies in 1952, he was sent back to Guinea-Bissau to work for the colonial Forestry and Agriculture department of the civil service. At the time, he was one of only four university educated natives of the Guinea-Bissau area.

Cabral used his time working as a civil servant to travel throughout the rural areas of the country studying the people and land-use issues. He reported on the environmental degradation and soil erosion caused by export-crops like peanuts, and also used the time to begin to educate and mobilize the population into demanding better status within the colony. His efforts did not go unnoticed – the Colonial Governor took steps and asked for Cabral to be transferred.

Cabral’s new position in Portugal had him spending significant amounts of time in Angola, where he made further contacts in the anti-colonialism movement. He even participated in the 1955 Bandung Conference, one of the first world meetings of Third World Nations and leaders.

Out of this, in 1956, came the two of the defining independence organizations of the Portuguese world – PAIGC, the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde; and the MPLA, the Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola.

Cabral did not believe Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde were ready to dive right into the armed independence struggle, however. Cabral insisted, and voiced this insistence in conferences in Havana and Italy, that fighting against the Portuguese could not happen unless there was a well-educated campaign to win support for the independence movement in the countryside. PAIGC soldiers were to be trained not only to fight, but to educate the rural populace into the reasons that such a movement was necessary and combine that with education into better land-management techniques. PAIGC soldiers were expected to work in the fields alongside the peasants when not actively fighting.

“The peasants would be the mainstay in our struggle,” Cabral proclaimed, but added it was necessary to “…struggle fiercely for peasant support.“

To that end, PAIGC set up training camps in Conakry and in Ghana (with the approval of Kwame Nkrumah) that combined military instruction with communication skills and lessons in agronomy.

When the fighting began in earnest, Cabral also made it a point to emphasize that PAIGC was fighting against imperialism and colonialism: not against white people, and not against the nation of Portugal itself. He saw the struggle to liberate African colonies as a struggle to free Portugal itself from fascism as well. The significant amount of time he had spent in Portugal left him with an appreciation for the culture that he did not shed during the battle for independence.

Cabral also constantly emphasized that PAIGC would be willing to stop fighting at a moment’s notice if independence could be achieved without armed struggle.

“We are ready at any time to cease hostilities in order to find a political solution to the conflict which opposes our people to the government of Portugal. Our only condition is the unequivocal recognition by that government of our inalienable right to independence.“

Sometime in the 1960s, Cabral became an asset for the Statni Bezpecnost, the Czechoslovakian security service, passing them intelligence under the code name “Sekretary”. Although passing information to Czechoslovakia rather than the Soviet Union seems to add an extra step in the dance routine, the truth is that the Soviet Union often used its satellite countries as a middle-man. Czechoslovakia was its preferred arms-funnel.

Indeed, a few weeks after Cabral’s assassination PAIGC would receive a shipment of Soviet surface-to-air missiles. It was a shipment that Cabral had gone to Moscow to lobby for just before his death.

In the immediate aftermath of the assassination, more than 100 military officers and guerrillas were summarily executed for involvement in the plot. Cabral didn’t live to see it, but his efforts were on the verge of success. The Carnation Revolution on 25 April 1974 was the final straw that pushed Portugal into freeing the rest of its colonial holdings. Just over a year after his death, the objective was accomplished. But without Cabral at the helm, independence goals changed. PAIGC adopted a more urban-based development plan that left the rural areas out in the cold yet again, and agriculture production began to fall.

Amilcar Cabral’s half brother, Luis Cabral, took the helm of the Revolutionary Council that would govern for ten years. He led the revenge killings of thousands of Guinean soldiers who had fought with the Portuguese, such as in the Bissora massacre, burying them in unmarked collective graves.

Today Guinea-Bissau has one of the lowest GDPs per capita in the world and has been beset by numerous coups and political fighting. It still follows the non-aligned foreign policy advocated by Amilcar Cabral, however.

Non-alignment for us means not aligning ourselves with blocs, not aligning ourselves with the decisions of others. We reserve the right to make our own decisions, and if by chance our choices and decisions coincide with those of others, that is not our fault. We are for the policy of non-alignment, but we consider ourselves to be deeply committed to our people and committed to every just cause in the world.

For more about the independence movement in Guinea-Bissau, please click here.

- January 20, 2021

- History , Interesting