The Shes Who are Hes

In 1917 a man died, and a few years later the marching army of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia destroyed his grave.

The West knew this man, but they knew him as a woman and only by applying a Western structure to the well known and codified Albanian practice of being a Burnesha, related in a 1911 article in the New York times:

A young girl, whose first name corresponds to that of the given name of the Maid of Orleans, is now being sung in the songs of the Montenegrin bards in the inns and coffee houses of Podgogritsa. When at the battle of Vranye last week her father, the hereditary commander of his clan, fell, she immediately stepped to his place and led the Martinais to victory against the Turks. Aside from the romantic phase of the affair, for Yanitza Martinay is very beautiful, the battle is important as showing that the Montenegrins on the frontier had joined with the Albanians.

According to a person who is well acquainted with her, this new Joan of Arc is not yet 22 years of age, and is “a tall, handsome, well-developed young woman. All the Albanian women are brave, and are trained from their girlhood to the use of firearms, and in times of war, as there are no mules, they carry the provisions and ammunition for their soldiers and go into the firing line to distribute them.”

The problem in this article is that Yanitza was not Yanitza, and she was not a she. He was Tringe Smajle Martinaj, a Burnesha from what is now Montenegro.

Martinaj was actually born female, but in accordance with the rules laid down in the Kanun i Leke Dukagijini, on the deaths of her brothers (fighting the Ottomans), Yanitza the daughter became Tringe Smajle the son when a vow was taken in front of twelve village elders, and transformed into a burnesha, literally translated as “he-she”.

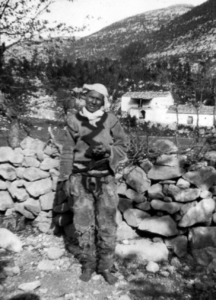

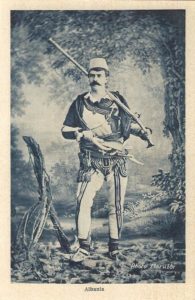

For the rest of his life neither Tringe nor any other Albanian would refer to him as female. He dressed in male clothes, he partook in male pastimes, he smoked, and as the article stated – he used his gun. Tringe Smajle would have, in fact, been thoroughly offended (and probably have started a blood feud) had he known that the New York Times was referring to him as female and comparing him to a female war leader. Under the Kanun, Tringe was absolutely male, allowed all male privileges, and no one was allowed to refer to any fact but that.

Tringe Smajle was renowned throughout Albania for distinguishing himself in two battles and as a later guerrilla leader. Songs about him are still performed today (although some facts are changed to align with political convenience) and he is considered a Hero of the People of Albania.

The cultural rules that allowed Yanitza to become Tringe Smajle exist in a collection of laws that were set down in the 1500s called the Kanun i Leke Dukagijini. Although the Kanun is attributed to the nobleman Leke Dukagijini, this was just the first formal collecting of the laws into one oral tradition. There is great debate among scholars as to the origins of the laws, with some believing that they were passed down from Illyrian tribal customs.

But wherever the Kanun originated, it governed everything from the economics and arrangement of the households, to legal murder, to how a woman could become a man. It was the final rule that allowed Yanitza to break out of the very oppressive female role and enjoy the freedom of being male.

Under the Kanun, women in Albania are relegated to a very tightly regulated role: they may not smoke, they may not drink alcohol, they may not enter certain village buildings, they are the property of the family, they must submit fully to their husbands – including accepting beatings at his whim. Women under the Kanun are not even allowed to wear a watch. It is not unusual for young girls under the age of 16 to be married to men who are twenty and thirty years older. And woe to any female who is found to no longer be a virgin on her wedding night – she is subject to the death penalty.

But declaring the oath to become a man has its own issues and struggles, foremost among them being the oath of chastity. A she may become a he only if there is a vow of lifelong chastity, which is given under the threat of death. In effect, in this world where family is everything and the young are depended upon to care for the old, the burnesha may escape the horrors of being female only by agreeing to a life of loneliness.

But to discuss the choice with the very few burnesha who remain today one finds out they have no regrets. In fact, the requirement to adopt male mannerisms is wholeheartedly embraced, and they often spout the same uncomfortable cultural devaluations of females as the men-who-were-born-men.

And it seems that today’s world has not had any more luck understanding the Burnesha than the 1911 New York Times. Far from being a statement of sexuality or fluidity, becoming a Burnesha is the way some women were able to deal with the intensely patriarchal system that developed in the mountains of Albania, Kosovo, and Montenegro. Being a Burnesha had nothing to do with sexuality, and everything to do with taking sex, both the verb and the noun, out of the picture entirely.

It is telling that the army of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia felt it necessary to destroy Tringe Smajle’s grave. Although he, too, fought the Ottomans – he was just too Albanian for the comfort of a Kingdom of Southern Slavs that was dominated by Serbians.

- May 20, 2020

- Albania