Three Players in the Balkan Sandbox

The last thousand years of Balkan history is a tale of three powers pulling on the limbs of an infant, as in the Biblical parable of Solomon’s wisdom. The Balkan baby is yanked first toward Austria, then toward Russia, and all the while the Ottoman Empire is pulling steadily on its legs.

The arguments between the Latin and Byzantine churches were just reaching a full boil when the Ottomans invaded and began their relentless advance. When Ottoman fortunes began to fade after the Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699, a split started to develop between the Austrian and Russian Empires. Formerly aligned in the goal of driving the Ottoman Turks out of Europe, now the two began to scheme against each other – while still working against the Ottomans – to gain the most out of the lands left behind in in the slow Ottoman retreat.

As long as Turkey was their common enemy, it was both possible and necessary to try to find a rationale for common action. But as soon as the opportunity arose to profit from the territorial losses of the Porte, shaken by their joint endeavors, it became clear that their objectives differed and even conflicted. — AV Florovsky

Austria, much closer in distance, viewed the Balkans as its specific sphere of influence from the start. The problem facing the Austrian regime was in the fact that there were huge Slav and religiously Orthodox populations, and this began to cause friction for the Austrians as early as the late 1600s.

In the 1680s, Austria invited the Serbs fleeing the religious persecution of the Ottoman Empire to settle in its frontier areas as defenders against the Ottomans over the border. This move, unfortunately, did not come freely, as the Orthodox who settled in Habsburg frontier areas were subject to intense pressures and coercions to convert to Roman Catholicism. By 1698 the Serbs in the Austrian Empire hoped to solve the issue, and so they appealed to Peter the Great of Russia to intercede for them with the Austrian government. The “Grand Embassy” was assembled and sent to, among a great itinerary of places, Vienna, where they received a stiffly negative reply.

But after the pomp and circumstance of the Grand Embassy retreated, the Russian diplomat P Voznitsyn managed to wrangle a concession from the Vienna that the Orthodox in the Austrian Empire would be granted religious freedom as long as the Catholics in Moscow would receive the same. Further, at some point in the negotiations it became an oblique understanding that Russia had the right to protect the religious liberties of the Orthodox in the Austrian Empire.

At this time Russia was not directly attempting to assert its influence over the Orthodox in the Austrian sphere of influence. When a Hungarian uprising occurred in 1703, Serbian troops supported the Austrian government against the rebellion with such exuberance that the Hungarian rebels, recognizing the Russian influence over other Orthodox practitioners, appealed to them for intervention against the Serbs.

Although the Orthodox in the Balkans were looking more and more to the Russian Empire as the guarantor of their freedom and religion, throughout the 1700s Russia was still heavily engaged in dealing with the Ottoman Empire on their southwestern border near the Carpathians and around the Black Sea. They didn’t have the military ability to intervene on behalf of the Balkan Orthodox, but that didn’t stop them from giving them consistent encouragement and constant appeal to the unity of the Orthodox community. These behaviors caused more and more consternation at the head of the Austrian government.

In an attempt to placate the Orthodox in the Balkans, Emperor Joseph I granted them some religious freedoms, but it was not considered enough, nor did it slow down the Orthodox turn toward Moscow. When Peter the Great began planning a campaign against the Ottomans that would culminate in the Pruth River Campaign, the Orthodox of the Balkans were ecstatic and strongly supportive. A massive public relations campaign (although it was not yet known as public relations) was instituted, with Peter releasing memorandums and missives extolling the suffering of the Orthodox under Turkish rule and appealing to the Balkan people to join the Russian army and drive the Ottomans out.

This, the Austrians knew, was too far. It would create a permanent idea in the minds of the Balkan Orthodox of Russia as the region’s saviors, effectively cutting out the possibility of Austria seizing the formerly Ottoman lands and converting those within them to Catholicism and a more Austrian culture.

No less a military genius than Eugene of Savoy had warned the Emperor that if the Tsar managed a victory that led to the fall of Constantinople, it would be worse for the Austrians than if the Ottomans conquered Europe all the way to Poland.

Austria decided not to ally with Russia, for the first time, against the Ottoman Turks. They also took more active measures, such as arresting any Orthodox Balkan fighters attempting to make their way to the Russian lines to join in the fight.

As a result, Russia’s attempt to topple the Ottomans was stopped by their Christian allies.

Russia and Austria continued to struggle over the issue of the Balkans – one claiming right of influence on the basis of proximity and the other on the basis of an “Orthodox Nationalism” (later referred to as Pan-Slavism). As the power of the Ottomans began to wane further, the Eastern Question began to loom larger and larger in the relationship between the two former allies.

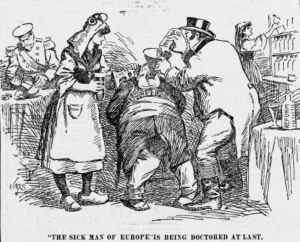

What should be done with the Eastern Question, the issue of the political and economic instability of the Ottoman Empire?

When Russia received the vague right to act as the protector of all of the Orthodox religion in the Ottoman Empire in the 1774 Treaty of Kucuk Kaynarca, it received a huge boost in regional power, but as Europe focused on dealing with the threat of Napoleon the fate of the Balkans took a back seat.

When the issue of the Balkans was revisited again in 1814-1815 at the Congress of Vienna, it was addressed not on the basis of the people and lands themselves, but as an extension (or non-extension) of Russian power. Austria’s purpose at the Congress was to promote a plan of conservative investment in the status quo, and the advancing power of Russia needed to be reigned in. To this end, although Russia gained a lot of land in the ensuing treaty, they received nothing in the Balkans. The issue of the decaying Ottoman borders weren’t even addressed, although they would continue to be a significant source of tension between Russia and Austria.

By the time the Greeks began a revolt against the Ottomans for their independence in 1821, the formerly liberal-leaning Tsar Alexander I had become disillusioned. The ultra-conservative Austrian diplomat Prince Metternich was able to talk him into not immediately supporting the Greeks in the interest of keeping the status quo. This caused considerable mental distress for the Tsar, who was conscious of Russia’s place as the “big brother” of the Orthodox world, but the biggest reaction of Russia to the revolution was to break off diplomatic relations with the Ottomans when the Ottomans executed Patriarch Gregory V.

Metternich was appealing to Alexander as an attempt to keep the status quo, but in reality his machinations behind the scenes were all a part of an attempt to keep the Russian Empire from expanding. To this end, although Austria wanted the Balkan lands of the Ottomans, Metternich also saw the need for a strong Ottoman Empire to balance Russian ambitions and influence.

Austria, Russia, and Prussia together formed the Holy Alliance, which was supposed to work in concert to install the divine right of kings and Christian values throughout Europe. In practice, it was against democracy, secularism, and revolution. It did, however, keep a nominal base tie between Austria and Russia until 1848. The two nations acted together when Miloš Obrenović of Serbia introduced the first European constitution, the Sretenje, in 1835. In this instance, the pressure to abolish the nascent constitution came from Russia. In 1849, Russian Tsar Nicholas I sent troops to Austria to help put down a Hungarian rebellion.

The two nations still continued their secrets and intriguing for influence in the Balkans in several ways, however. First, in the main battleground of Serbia, Russia supported the Karađorđevič family while the Austrians lent their support to the rival Obrenovićs. When the Karađorđevič Prince, Alexander, was in power in Serbia from 1842 to 1858, Miloš Obrenović was living in Austria. Later, the Russian royal family would welcome the son of Alexander Karađorđevič when the pro-Austria Obrenović family was returned to power.

The last semblance of any alliance ended in 1853 with the Crimean War, when Austria remained hostile-neutral as the Russians fought. This would directly lead to the long tumble of Austria from its heights as a Great Power, as Russia then refused to intervene in either the 1859 Franco-Austrian War when Austria-Hungary lost all influence in Italy, or the 1866 Austro-Prussian War which ended the influence of Austria on most of the Germanic states.

But Austria still exerted influence when the 1856 Treaty of Paris was signed, and the Great Powers of Europe agreed to prop up the Ottoman Empire in the interests of keeping peace in Europe by excluding Russia from expansion.

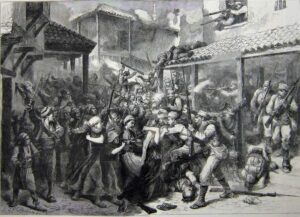

Freed from having to defend borders with the Ottomans constantly, Russia was able to start poking their nose into more Balkan affairs – usually with whispers of Slavic brotherhood and offers of covert support. When the Herzegovinian Uprising and the April Revolution in Bulgaria encountered terrible response and atrocities against Balkan Christians by the Ottoman Empire, Russia finally went to war with the Ottomans specifically for the benefit of the Balkan Orthodox Christians… and territorial gain for Russia. It was a resounding success, and possible because Austria agreed to stand neutrally in exchange for the territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The Russo-Turkish War ended with the Treaty of San Stefano, a treaty that wildly tipped the balance of power in the Balkans toward Moscow; with Bulgarian independence and Serbian land grants guaranteeing Russia a very friendly path of access to the Adriatic and warm water ports.

The Great Powers came together once again, abrogating the Treaty of San Stefano and introducing their own Treaty of Berlin in 1878. Serbia and Montenegro were granted independence, but Bulgaria, without any input by the Bulgarians themselves, was reduced to the status of autonomous province of the Ottomans. Bosnia and Herzegovinan was “occupied and administered” by the Austro-Hungarians.

Russia’s actions in the Russo-Turkish War loomed large to the Orthodox population of the Balkans, who saw them now as liberators from Ottoman Oppression. Although the King of Serbia, Milan Obrenović, was pro-Austria, the Russians were hosting and educating the rival Karađorđevič Dynasty. As a result, when the behind-the-scenes intrigues of Austria-Hungary and Russia played out in the Balkans post-Treaty of Berlin, the area moved very firmly toward the Russian sphere of influence.

For more information on Balkan history, please click here.

- February 19, 2021

- Bosnia and Herzegovina , Bulgaria , Greece , Montenegro , Serbia