We Must Stop the Bear!

The Balkans has always been a point of contention between the East and the West, and although the various incarnations of Hungary, Austria, and Austria-Hungary tended to dominate next to the advancing Ottoman Army, Russia was always nipping at the edges and creating leverage with the large number of Orthodox Slavs in Central Europe. That all began to change in the 1800s, when Russia’s burgeoning empire finally had the time, money, and troops to begin to devote more toward a Pan-Slavic Balkans.

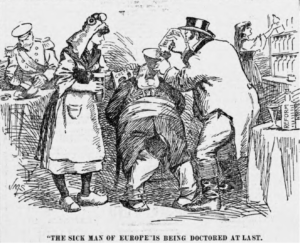

At first allied with Austria through treaty, by 1848 Russia was going its own way and Austria-Hungary was worried. More and more Slavs flirted with the ideas of Pan-Slavism, turning away from the influence of the Catholic Austria-Hungary. Urgently working to keep Russian power at bay, the rest of Europe’s Great Powers began propping up the decaying Ottoman Empire, known as The Sick Man of Europe. The Ottomans, formerly the enemy of all Christian nations, were now seen as the last bulwark keeping Russia from uniting Slavs and depriving Europe of any hope of influence in the Balkans.

When Russia decisively defeated the Ottoman Empire in the Russo-Turkish War in 1878, the initial Treaty of San Stefano shocked the European world. On 3 March 1878 Russia sought to completely change the face of the Balkans:

- Bulgaria was to become an autonomous and self-governing principality of the Ottoman Empire. It would have a Christian government and the right to keep an army, with a prince elected by the people. The nobles were to draft a constitution. While Ottoman troops were to withdraw from Bulgaria, Russian troops were to stay in-country for two years.

- Montenegro was to double its territory and become a fully independent principality.

- Serbia was to gain multiple cities and become a fully independent principality.

- Romania was to become an independent principality and gain Northern Dobruja, but would cede Southern Bessarabia to Russia.

- Russia was to receive swathes of what is now Georgia and Armenia.

- Bosnia and Herzegovina would become an autonomous province.

- The Bosporus and Dardanelles would be open to all neutral ships.

Bulgaria was the most blessed country of the San Stefano Treaty, gaining enormous swathes of land, which included most of what is now Northern Macedonia. However, the point of Greater Bulgaria was not merely to free Bulgarians from the Ottoman yoke, but to give Russia a large amount of friendly territory which would allow them access to the Mediterranean. Close allies united in religion and ethnicity would create a strong bond even more favorable than gathering Balkan nations into a larger Russian Empire. In short, Russia, on her own, had attempted to solve the Eastern Question of what to do with the rotting Ottoman Empire by placing south-eastern Europe under Russian domination.

The European Great Powers took one look at the treaty, which Russia would later insist was only meant to be a rough draft, and recoiled in shock at the newly dominant position Russia would receive in Europe. While two hundred years previously the issue had been an Ottoman Empire snarling at European borders, Western Europe now envisioned a Russian bear gobbling at the honey of established Europe; the specter of Pan-Slavism needed to be exorcised.

The opinion of Prince Eugene of Savoy sixty years earlier, that the Ottoman Empire pushing all the way to Poland would be preferable to a vigorous and expanding Russia, still held true at the end of the Russo-Turkish War. Very quickly, the European Great Powers called for a Congress to renegotiate the Treaty of San Stefano and limit the gains Russia had made.

The six great European powers of Russia, Great Britain, France, Austria-Hungary, Italy, and Germany were represented at the Congress. Also attending, but not allowed to participate, were the Balkan nations at question: Greece, Serbia, Romania, and Montenegro. The Ottoman Empire also attended, but only as an observer – and not an honored observer by any means.

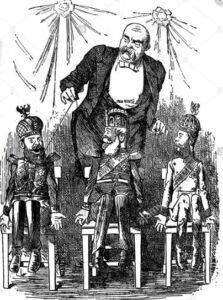

The Congress of Berlin was held from 13 June to 13 July 1878 at the Reich Chancellery and hosted by Otto von Bismarck. Germany had no intentions in the Balkans, and thus Bismarck could make the claim that Germany was impartial, wielding his supposed impartiality like a hammer to keep control of the various nations represented at the discussions. In reality, Bismarck did have an agenda – to stabilize the Balkans by diminishing Russian gains and preventing Greater Bulgaria. These aims were supported by the rest of the European powers: Austria-Hungary was eager to negate the possibility of a Slav revolt in Habsburg lands. Great Britain and France were both worried about Russia expanding in the south, into Egypt and Palestine – both areas where France and Great Britain had colonial aspirations. The British also considered the Mediterranean as their specific sphere of influence, and Russia’s new intrusion was anything but welcome.

Between Bismarck’s iron fist of “neutrality” and his cranky demeanor due to the heat of summer, the Congress went forward with far less argument, grandstanding, or meandering pointless side conversations than any other meeting of powerful nations in history.

By the end of the Congress, with the signing of the Treaty of Berlin, the entire face of the Balkans had been redrawn. Eighteen of the twenty-nine articles of the Treaty of San Stefano were eliminated or changed, sharply curtailing Russia’s new power.

“I consider the Berlin Treaty the darkest page in my life,” said Alexander Gorchakov, the Russian representative. His views represented those of the Russian public in general, who were furious at the repudiation of the gains made after a war in which Russians had fought and bled to finally defeat the Ottomans while the rest of Christian Europe sat out and watched from a distance.

Although Bulgaria was still granted autonomy, it was divided and then split again into Bulgaria and Eastern Rumelia. Macedonia ands Kosovo were returned to the Ottoman Empire, but Bulgaria was given nominal assurances against Ottoman interference. Russian access to the Mediterranean was again blocked.

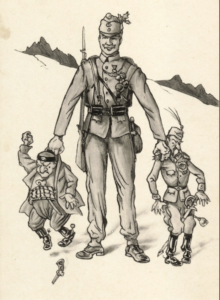

Serbia, Romania, and Montenegro were given their promised independence, but Montenegro was also given strict rules about use of their coastline and ocean access. This, along with the Austro-Hungarian occupation and administration of the Sandjack of Novi Pazar that kept Serbia and Montenegro separated, blocked another possible route for Russia to reach the Adriatic.

Bosnia and Herzegovina were also transferred to Austria-Hungary’s sphere of influence. Although still officially part of the Ottoman Empire, it was to be occupied and administered by Austria-Hungary.

But many Balkan issues were also ignored at the Congress. Italy was dissatisfied with an outcome that didn’t grant them their former Istrian empire. The border between Greece and the Ottomans was not resolved.

In the final analysis, the biggest problem of the Treaty of Berlin was, “…an essential feature of the treaty was its disregard of ethnic and nationalist considerations… For the Balkan peoples, then the Treaty of Berlin meant frustration of nationalist aspirations and future wars,” said L. S. Stavrianos.

Diplomats of the late 1800s agreed with Stavrianos’s assessment.

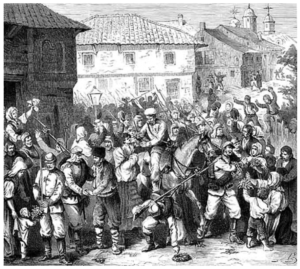

No remonstrances on the part of the local populations against being thus summarily transferred without being consulted, to the tender mercies of a strange government, are to be attended to; armed resistance in defense of their homes and hearths is to be termed insurrection, and the net result, ‘peace with honor!’”

Russia ended the Congress frustrated, and fully blamed Germany for their losses, which irreparably and deeply damaged the relationship between the two nations. The resulting anger caused a deeper alliance between Germany and Austria-Hungary, which would result in the 1879 Dual Alliance that directly agitated the world into war. Increasingly obvious to all, however, was that the great Austria-Hungary which spread over so much of Europe was quickly becoming the weaker partner in the Austria/Germany relationship.

As one pundit said later in 1878, “In a word – when Austria signed the Berlin Treaty she became a party to what, in all probability, will prove her own death warrant.”

Russian hegemony and Pan-Slavism had been temporarily defeated in the Balkans, but it left behind a simmering anger about which the other Great Powers seemed oblivious.

That anger simmered, and then boiled, and then finally erupted into a conflagration that would burn nearly every nation of the world.

To read more about Russia in the Balkans, please click here.

To read more about World War I and the lead up to war, please click here.

For more history of the 1800s, please click here.

- February 24, 2021

- Bosnia and Herzegovina , Bulgaria , Croatia , Serbia