The Plague that Killed the Emperor

“Is any man afraid of change? What can take place without change? What then is more pleasing or more suitable to the universal nature? Can you take a bath unless the wood undergoes a change? Can you be nourished unless the food undergoes a change? Can anything else that is useful be accomplished without change?” —Marcus Aurelius, Meditations

Marcus Aurelius seemed destined for greatness from the beginning. Although his father died when he was very young, his family focused a great amount of effort on him, schooling him at home with tutors as was normal for prosperous families at the time.

The future emperor became immersed in philosophy almost from the beginning of his schooling, a strong forecast of the Stoic philosopher-king he would become. And Marcus Aurelius kept up his habit of learning through his entire life. As an older man he responded to someone asking him where he was going by saying, “It is good even for an old man to learn, I am now on my way to Sextus the Philosopher to learn what I do not yet know.”

Marcus Aurelius’s reign, although marked by plague, war, and persecution of Christians, was looked back upon with great fondness as a golden period in Roman history. No less an eminent historian than Edward Gibbon, who wrote The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, described the time as, “…the happiest and most prosperous period.” Nor was that the opinion of someone centuries removed and wearing rose-colored glasses. The historian Herodian, writing directly after Marcus Aurelius’s death, described him thus, “Alone of the emperors he gave proof of his learning not by mere words or knowledge of philosophical doctrines but by his blameless character and temperate way of life.”

It is interesting that the past and Marcus Aurelius’s reign is viewed in a nearly hagiographical manner by almost all past and present historians, as it was in his reign that the Antonine Plague struck Rome. And the plague was devastating; although estimates for the amount of dead vary, none of the numbers are small. At the lowest end, the Antonine Plague killed 10% of Romans. The upper end of death estimates is even more horrifying – up to 30% of the empire succumbed. At the height of the first wave of the plague 2000 people were dying per day in Rome alone.

The societal results were staggering. The Roman army, a model of efficiency and efficacy, was decimated. Desperate to make up manpower shortages as the unrest amongst the Gauls on the border took hold, Marcus Aurelius began to lower recruiting standards. He drafted farmers and lower petty bureaucrats, as well as pulling from trained gladiators.

Not only did this affect the actually fighting ability of the Roman forces, it had serious ripple-down effects within Rome itself. Fewer farmers meant that less land was cultivated, leading to shortages of food. Fewer bureaucrats mean that infrastructure was neglected and crime rates rose. Fewer gladiators meant that a nation under intense stress was left without the outlet of entertainment just when they needed it most. And fewer people meant that government revenue declined sharply just when it was needed most to defend the borders of the empire and sponsor programs to blunt the ripple effects the plague was creating.

In short, although the Gibbon’s seminal work The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire dates the fall to the Plague of Justinian, it was the Antonine Plague that upended the very foundations of the empire and started the walls to crumbling.

As with the most recent pandemic, the Antonine Plague – thought by most historians to be the emergence of smallpox – most likely came to the Roman Empire from China. It was brought back by the army from engagements in Mesopotamia, and explained by two slightly different stories. In the first one, the Roman general Lucus Verus opened a closed tomb in Seleucia during the sacking of the city, releasing the contagion on the world as a punishment by the gods for violating a vow not to sack the city. In the second story, a Roman soldier opened a golden casket in the Temple of Apollo in Babylon, allowing the plague to escape.

In both instances, the arrival of the plague was seen as a punishment by the gods. Roman society was no stranger to diseases carrying off members of society, but the Antonine Plague roared into their world with a virulence that even they could not process other than to pin the blame on divine anger.

And not only were the numbers of dead staggering, the manner in which they died was terrifying. Within three weeks a victim would go from perfect health to vomiting, black diarrhea, and a disfiguring rash over their entire body. If they survived, and modern analysis of smallpox death rates place the survival figure at around 70%, victims would carry immunity for the rest of their lives. They also likely carried severe scarring, as evidenced by the extreme pockmarks exhibited by no less than the French revolutionary Robespierre; scarring so deep it is visible even on his death mask.

Fear of the plague was so profound in Roman society that archaeologists working in areas settled during the plague times frequently encounter amulets and prayers meant to ward off the contagion. Archaeology has also confirmed that the death counts were so high that ordinary funeral rights were abandoned in the interest of disposing of bodies as quickly and efficiently as possible.

There is not a lot of information about the Antonine Plague, but not because there were no records kept. The Roman Empire was nothing if not a stickler for paperwork. Other than the descriptions of the physician Galen, most of the records relating to the plague were destroyed in subsequent centuries as wars wracked the Empire from every direction. However, Galen’s descriptions were marvelous bases for epidemiological historians to begin.

There was another interesting consequence of the Antonine Plague: the rise of Christianity. In line with the reaction of many Romans of the day, Marcus Aurelius began a persecution of the Christians. The belief was that, by refusing to offer sacrifices to the Roman gods, the Christian community had angered them and brought the divine wrath of the plague down upon the world.

The difference in this persecution was in the Christian reaction to the plague. Rather than fleeing, as many of their neighbors did, the Christian community stayed put and extended themselves feeding, sheltering, and nursing plague victims. A tremendous amount of goodwill was built amongst the pagan community toward those who served on the front lines of the plague. As well, Christian beliefs in the afterlife and the promise of salvation after death appealed to many pagan Romans during the apocalyptic scenes of death and decay. Conversions to Christianity increased with such rapidity that it became the official religion of the Roman empire less than 150 years after Marcus Aurelius’s death.

So, coming full circle back to Marcus Aurelius, it is perhaps no surprise to anyone that he himself succumbed to the plague while on campaign in March 180. The location of his death is a bit contested – most historians believe he died in what is now Vienna, but there is some indication he may have died in what is now Sremska Mitrovica in Serbia.

And it is a testament to the leadership of this Emperor, the last of the Stoic philosophers, that even though the Roman Empire was being decimated by plague and the fallout from the plague’s effects, his rule is still considered a Roman golden age. Roman citizens, looking back at the bleak times of death, saw it as a time when they came together to develop new ways of forging ahead in the unique challenges the first world pandemic presented.

Perhaps Marcus Aurelius said it best himself, in his journal Meditations, “The more we value things outside our control, the less control we have.” Survival during the horrors of the Antonine Plague required iron self control, fortunately modeled for all to see by a Stoic emperor.

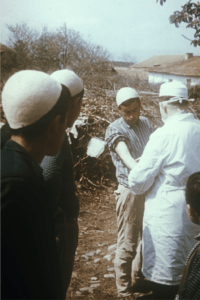

The reign of terror of smallpox largely ended where it began. In 1972 the last European outbreak of the disease cropped up in what was then Yugoslavia, 2000 years after the same territories had been a vital center of the plague-ridden Roman Empire. With decisive action, the government of Yugoslavia acted immediately: martial law was declared, hospitals were readied for thousands of victims, and the entire population of Yugoslavia was vaccinated within weeks.

It worked. While 175 people were infected and there were 35 deaths, the toll was far less than the best day under the Antonine Plague.

Within eight years, approximately 1700 years after the first smallpox pandemic, the disease was declared completely eradicated from the world.

- August 10, 2020

- Serbia