A Person Over Whom The Right of Ownership is Exercised

It is easy to assume the end of slavery as the end of the American Civil War. Although, for true understanding, there is a much more nuanced discussion necessary of societal and personal reasons causing people to take up arms to free others not of their own ethnic group; the most basic and simple point to be made is that the United States was one of the only nations where non-slaves fought other non-slaves to free slaves.

Nor was the freeing of slaves in the United States the end of legal slavery. Merely in the period from 1900 to the present day, more than 29 countries have made owning and trading in slaves illegal, with some anti-slavery laws going on the books as late as 1981 in Mauritania. In the early 1960s in Saudi Arabia as many as 300,000 people were held in legal slavery.

In fact, the United Nations made addressing issues of slavery a cornerstone of their Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, stating, “No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms.” Even as late as 1948 it could not be taken for granted that slavery did not exist, or even that it was unequivocally on its way to eradication.

Slavery is not a problem of the past, but it is a problem rooted in the past. It is mentioned in the earliest human histories in various forms and it was addressed over thousands of years in various ways. In many European countries, chattel slavery gave way to serfdom before the Renaissance although these same nations would often also participate in the Atlantic Slave Trade. Portugal was an exception to this, with slavery persisting within Portugal’s borders until 1761. At one point, in 1552, 10% of the population of Lisbon were slaves, and although most were of African origin, there were also a number of slaves from Japan and moriscos (Muslims who were forced to convert to Christianity after the Reconquista).

The British Empire began solid efforts toward eradicating slavery in their dominions in 1807 with the Slave Trade Act, and a final addressing of the issue within the empire with the Indian Slavery Act of 1843.

France abolished slavery throughout their empire in 1848 and the Netherlands, who had been a great part of the slave trade, in 1863. The nineteenth century was certainly when the long-accepted practice of humans owning other humans came to be seen as something repugnant that should be discouraged with severe penalties.

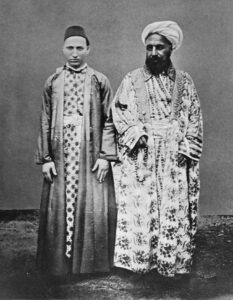

But criminalizing slavery and slave trading was not a juggernaut movement everywhere. In the Ottoman Empire, where the entire base of the the government bureaucracy for several hundred years was based on a system of seizing the sons of Christians in the Balkans, called the Devshirme, female slaves were still being captured and sold openly as late as 1908. This was tacitly condoned even though the Ottoman Empire had signed the 1890 Brussels Conference Act, which was specifically designed to end slavery and slave trading. The sultan himself did not free his slaves until 1909, and his family members were not required to do so at the same time (nor did they). Armenian girls were sold as slaves during the Armenian genocide in 1915, and although Kemal Ataturk legally ended slavery in the 1920s, legislation specifically criminalizing slavery in Turkey was not formally introduced until 1964.

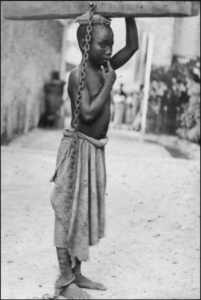

Slavery in Zanzibar, long a hub for the transport of black slaves from Africa to the Arab world, continued into the twentieth century, with David Livingstone estimating that up to 80,000 Africans died yearly during transport to the Spice Island. Official accounts usually date the end of slavery on the island as 1897, but that does not in any way take into account concubines who were forced to remain in sexual service until 1909. As with most places that outlawed slavery, women were often the last to be allowed freedom.

In Korea slavery was officially outlawed in the Gabo Reform of 1894, but the practice of slavery continued on a very small scale until the 1930s. This does not take into account the modern slavery practiced by the state in North Korea, the only state in the world which has not explicitly criminalized any form of modern slavery.

Although some states were slow to criminalize slavery and slave trading, there was a true concerted world effort in the nineteenth century to work toward a slave-free world society. The Brussels Conference Act of 1890 stated “[This is designed to] put an end to the Negro slave trade by land as well as by sea, and to improve the moral and material conditions of existence of the native races.“

The Brussels Convention was supplemented in 1919 by the post World War I treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, which claimed to “endeavor to secure the complete suppression of slavery in all its forms and of the slave trade by land and sea.“

But the most comprehensive leap toward eliminating slavery and the slave trade in the world came about on 25 September 1926 with the 1926 Slavery Convention signed in Geneva, Switzerland under the auspices of the League of Nations. This treaty, now administered by the LoN successor the United Nations, is still in effect today and 99 countries have committed to participation.

One way in which the 1926 convention was groundbreaking was that it actually defined what a slave was. Now there was a legal definition provided by a world body. “Slavery is the status or condition of a person over whom any or all of the powers attaching to the right of ownership are exercised.” The convention also created concrete measures that signatories must agree to undertake to eliminate all facets of slavery.

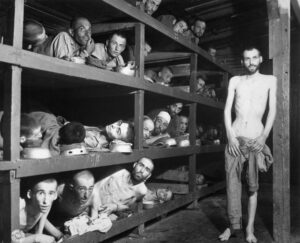

Where the convention unfortunately fell short was in failing to establish procedures to review incidences of possible slavery and to methods of punishment for those in violation. This was made manifestly clear after World War II, when the Nazi system of forced labor and concentration camps, a modern incidence of widespread ethnically-driven slavery, became common knowledge.

To this end, the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights was adopted by the United Nations. This declaration states that all humans are “born free and equal in dignity and rights,” and furthermore, “Everyone is entitled to all the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration, without distinction of any kind, such as race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.“

But even then, the evolving understanding of ways that humans could be enslaved meant that more updates were needed. In 1956, the Supplementary Convention of the Abolition of Slavery was signed. It was in this supplement that, finally, the unique situations that confronted women and could result in legal slavery were addressed. Servile marriage and child servitude were outlawed, and minimum age for marriage was mandated. As well, public consent to marriage was encouraged.

The supplement also addressed the issues of debt bondage, serfdom, permanent marking of slaves and servants, and criminalized slave trafficking.

Unfortunately, despite the vast efforts of the last 200 years, slavery continues. Currently, between 21 and 46 million people are held in various forms of slavery, depending on the definition used to define a slave. There are modern slaves held in forced labor situations, the sexually exploited, and approximately 15.4 million people in forced marriages. Most worrying of all, those held in modern slavery are worth even less than those held in historic chattel slavery. Humans held as slaves have become more disposable, and 71% of those held in modern slavery are female.

Slavery is an issue rooted in the past. But slavery is still not in the past.