The Death of the Archbishop

On the front of Westminster Abbey in London are the statues of the 20th Century Martyrs. Amongst them is a Ugandan Archbishop who refused to leave his post to save his life and fell victim to one of the most savage regimes of the 20th Century. His death proved the turning point in the regime of Idi Amin; the moment when Amin’s ministers realized that no one would ever be safe and began to flee. The moment when the international community realized that something would have to be done in Uganda was when Idi Amin ordered the death of the Archbishop Janani Luwum on 16 February 1977.

Janani Luwum was not born a Christian. Although his exact birthdate isn’t known, he was born sometime in 1922. He converted to Christianity in 1948 when he was 26 years old, and from there his rise in the Ugandan church was nearly meteoric. He was ordained a priest in 1954, studied twice in the United Kingdom, was consecrated the Bishop of Northern Uganda in 1969, and in 1974 was appointed the Archbishop of the Metropolitan Province of Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, and Boga.

It was not a good time to lead a Christian church in Idi Amin’s Uganda. It was not a good time to be in Idi Amin’s Uganda. In his 1975 Christmas broadcast, Amin accused the church of preaching bloodshed and hatred. He also banned church fundraising. But Archbishop Luwum took his role seriously. He was a constant critic of the Amin regime and attended all government meetings. His attendance at the meetings and his willingness to meet with Amin to discuss the church’s view on the government’s actions not only infuriated Idi Amin, it even met with criticism from those who viewed it as kowtowing to the same regime he was criticizing daily.

“I face daily being picked up by the soldiers,” Luwum replied to his critic. “While the opportunity is there, I preach the Gospel with all my might. My conscience is clear before God that I have not sided with the present government, which is utterly self-seeking. I have been threatened many times. Whenever I have the opportunity I have told the president the things the church disapproves of. God is my witness.”

On 30 January 1977, one of Luwum’s bishops read a sermon in the presence of government officials that emphasized the sanctity of life. It was a response to Amin’s purge of those accused of siding with his nemesis-in-exile, Milton Obote; a purge that included completely annihilating Obote’s home village, leaving no one alive.

The response to the sermon was swift. On 5 February Amin’s soldiers appeared at Archbishop Luwum’s house and tricked him into opening the door by ordering a man named Ben Ongom, whom they had tortured extensively, to beg for help.

Luwum opened the door to aid the man. He described what happened next in a letter to the Anglican bishops:

So I opened the door and immediately these armed men who had been hiding sprung on me corking their rifles and shouting, “Archbishop! Show us the arms!” I replied, “What arms?” They replied, “There are arms in this house!” I said, “No.”

At this point their leader put his rifle in my stomach on the right hand side while another man searched me head to foot. He pushed me with his rifle, shouting, “Walk! Run! Show us the arms!”

[Ongom then said]… Archbishop, you see some time back we brought some ammunition and divided it up with Mr. Olobo who works in the Ministry of Labour in Kampala. I have suggested to the security men that Mr. Olobo might have transferred the ammunition to your house. Please help.

The Ugandan security officials searched and ransacked the Archbishop’s residence until 4:30 in the morning. After they departed, Luwum’s wife Mary begged him to flee Uganda into exile. Many others urged him to depart as well.

“If I, the shepherd, flee, what will happen to the sheep?” Archbishop Luwum answered them. He refused to leave Uganda.

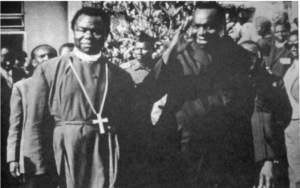

Within two days the Archbishop was called to a personal meeting with Idi Amin. His wife refused to let him go alone, an action that most likely saved Luwum from being imprisoned and murdered that same day. At the meeting Amin tried to justify his reasons for ordering Luwum’s home to be searched and took several pictures with the Archbishop to distribute in order to prove that he had not had the man murdered as rumored.

It was to be a short respite. “I think I was marked to be killed on Monday at Entebbe,” Luwum told one of his bishops.

Still, the bishops of Uganda were not ready to back down and they decided to directly confront the issue of the Archbishop being harassed by Ugandan soldiers while at home on faked charges. They decided to take the opportunity to address not only the invasion of the Archbishop’s home, but also the increasing numbers of arbitrary killings and mass arrests and torture being done by Amin and in his name. They requested a meeting with Amin and released their memorandum of protest on 12 February 1977, sending copies not only to the government and Idi Amin himself, but also to the Catholic, Orthodox, and Muslim faith communities throughout Uganda.

The gun whose muzzle has been pressed against the Archbishop’s stomach, the gun which has been used to search the Bishop of Bukedi’s house, is the gun being pointed at every Christian in the church.

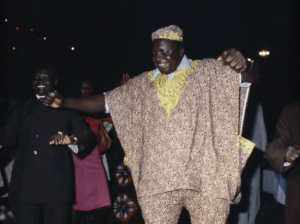

Amin’s reaction was swift. On 16 February Archbishop Janani Luwum was arrested and the bishops, along with government cabinet members, were invited to a meeting at the Nile Hotel. They arrived on time, only to find a huge pile of arms in the front of the room, surrounded by soldiers. At 11 am, Idi Amin’s most feared army officer, Colonel Isaac Malyamungu, rose to the front to make a statement. Confessions from those who implicating Archbishop Luwum and two others in trading illegal arms in support of Milton Obote were read, and when Amin finally addressed the crowd he asked for all those who supported the death penalty of the accused to raise their hands.

The soldiers in the front started roaring. “Kill them!” they shouted in Kiswahili.

The Archbishop and the two other accused were led away. As he left, Luwum turned to Bishop Festo Kivengere and said, “They are going to kill me. I am not afraid.”

Archbishop Janani Luwum was correct. He died that day. That night, Idi Amin held a raucous party, to which he had invited all the soldiers and cabinet members present at the rally to condemn the Archbishop. Only the soldiers attended.

The next day, when Amin was officially “informed” of the deaths of the accused, he responded, “God has given them their punishment.”

Amin, of course, already knew that the Archbishop was dead. Several reports place him at the scene of the torture and death, although no one has been able to state with certainty if it was Amin whose gun ended Luwum’s life.

As with most of the Idi Amin regime’s extra-judicial killings, the official story was nowhere near the truth. Officially, the three accused men attacked the driver in an attempt to escape and died in the resulting car crash. Amin’s soldier’s even staged a scene using two Land Rovers which had been previously totaled in an accident, although they neglected to remove or obscure the license plates which made examining the evidence a bit easier for outside investigators.

In reality, the three men were taken to the army barracks and heavily beaten and tortured before being shot.

The families were not allowed to take possession of their loved ones’ bodies, but most of the Archbishop’s family had fled to Kenya upon his arrest leaving behind only his elderly mother, an uncle, and a daughter. Not allowing families access to the bodies, if there was a body to be claimed at all, was standard in the Amin Regime: it kept people from independently examining the tortured remains of Idi Amin’s victims and challenging the official death stories of the regime.

After several days, soldiers brought Archbishop Luwum’s body to the house of his mother, where she was sitting alone and unaware that he had been arrested. They demanded that she tell them where to bury him, and she directed them to the village graveyard.

It was already evening and the soldiers had trouble digging a grave in the rocky soil of the village, so they abandoned their attempts and left for the night, warning Luwum’s mother that they would return the next day and that no one was to approach the coffin.

Archbishop Luwum’s mother and the other villager ignored the warning and unsealed the Archbishop’s coffin, It was then that his extensive torture and several bullet wounds, including one through his mouth, were discovered and recorded.

Archbishop Janani Luwum remains buried in the same spot today, and his grave has become a pilgrimage site. His statue is also amongst the Twentieth Century Martyrs on Westminster Abbey. But perhaps most importantly is that his death turned out to be the turning point in the terror regime of Idi Amin. When Amin felt comfortable killing the Archbishop of Uganda, a prelate of the Anglican Church, the international community stopped dismissing him as a cartoonish savage and began supporting the movement to remove him from power.

Janani Luwum left behind a wife and nine children, of whom seven survived to adulthood. Their life was extremely difficult after Luwum’s death, and even with a church stipend it was difficult to make ends meet. Many of them returned to Uganda after Idi Amin was removed. His wife, Mary Lawinyo Luwum, died in 2019, 42 years after the death of her husband.

To read more about Uganda’s history, please click here.