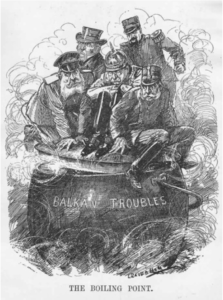

Yet Another Balkan Crisis

The provinces of Bosnia and Herzegovina shall be occupied and administered by Austria-Hungary…Austria-Hungary reserves the right to maintain garrisons and to have military and trading roads over the whole area of that portion [the Sandjak of Novi Pazar] of the ancient Vilayet of Bosnia.

The diplomatic coda to the Pig War of 1906-1908 became, like the musical coda to The Beatles ‘Hey Jude’, the longest lasting bit of the whole piece.

Throughout September 1908, the Russian Foreign Minister Alexander Izvolsky and the Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Alois Aehrenthal communicated secretly about breaking certain provisions of the 1878 Treaty of Berlin. Most specifically, Austria-Hungary wanted to annex Bosnia and Herzegovina and Russia wanted to be able to send their warships through the Bosporus Strait in Ottoman Turkey. Both were mainly negotiating for their nation’s “reaction”, that is – an assurance that the inevitable loud complaints of the other Great Powers upon the treaty abrogation would not be repeated by either Austria-Hungary or Russia.

Russia, in particular, was engaged in a large round of double-dealing. Since the overthrow of the Serbian Obrenović Dynasty in 1903, the newly installed Karađorđević Dynasty had their face firmly looking toward Russia and was thoroughly inculcated into the Pan-Slavic movement. As a part of that movement, the Slavic inhabitants of Bosnia and Herzegovina were considered by Serbia as a natural addition to a southern Slav nation. The Serbs would, of course, be in charge of this union of southern Slavs.

Russia had repeatedly encouraged this attitude within Serbia, as well as supporting Serbian attempts to free themselves from economic dependence on Austria-Hungary. To this end, Russia had been encouraging treaties between Balkan nations that pushed the Austro-Hungarians out of the Balkans along with the Ottomans.

Serbia had placed their trust in their Slavic “big brother,” but the Russians were not being entirely honest and straightforward with Serbia. The secret negotiations between Izvolsky and Aehrenthal were a strong example that all was not Slavic brotherhood and roses at the top of the hierarchy.

On 16 September 1908, the two diplomats met at Buchlau Castle for six hours. Although later, the lack of proof of the agreements would initiate a massive diplomatic uproar, it is generally accepted that there were three main agreements:

- Russia would maintain a friendly attitude when Austria-Hungary annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina.

- Austria-Hungary would withdraw its troops from the Sandjack

- Austria-Hungary would also not protest when Russia used the Bosporus Straits to move its warships.

The secrecy surrounding the Buchlau Bargain was strong that even the Prime Minister of Russia, Pyotr Stolypin himself, did not know the negotiations were going on. When the agreement came back to Russia to be ratified, Stolypin absolutely refused, saying that under no circumstances should Russia support any more Slavs coming under a Germanic ruler no matter what the gain would be for the Russian Empire itself . Stolypin underlined his determination by threatening to resign if the Buchlau Bargain were to be entered into officially.

Russia decided to back down, Izvolsky’s negotiations were to be for naught.

As planned, when the Bulgarians announced their independence from the Ottoman Empire, the Austro-Hungarians released their plan to annex Bosnia and Herzegovina. An immediate uproar ensued amongst the Great Powers and the other Balkan nations. On 6 October, the annexation was announced. On 7 October, as Austria-Hungary was announcing their withdrawal from the Sandjack, Serbia began mobilizing its army and sent a letter of protest to Austria-Hungary. Receipt of the letter of protest was refused, on the grounds that Serbia had not been a signatory to the Treaty of Berlin, no matter whether they were affected by the annexation or not. Austria-Hungary’s flippant response to Serbia certainly did not help resolve matters peacefully.

The rest of the Great Powers, in a surreal foreboding of what was to come in July of 1914, began to issue their own responses to the annexation, and most of them came down particularly hard on Russia as well, for sneakily supporting the Austro-Hungarians behind the scenes. Izvolskey had no option other than a straight denial, which rang completely false.

“I have applied myself above all to destroying the false impression created here by the Ambassador of Austria-Hungary as though his government proceeded to the annexation with the approval of Russia and Italy. I replied immediately that on the contrary I had stated positively to Baron Aehrethal that we considered the annexation as a violation of the Treaty of Berlin and a subject for the deliberation of the powers.”

Aehrenthal had two smart responses to the factually incorrect claims of Izvolskey. The first was spoken, “M. Izvolskey never expressed himself to me in this fashion; we agreed in Buchlau that we would respond to the friendly attitude of Russia in the question of the annexation by a similar position in the question of the Dardanelles.”

Secondly, Aehrenthal and the Austro-Hungarian government began releasing documents showing Russia’s straddling of both sides in the Slavic sphere. The embarrassment to Russia was tremendous. Izvolskey responded not with a refutation, but by denouncing the assumed Jewish heritage of Aehrenthal, “The dirty Jew has deceived me. He lied to me, he bamboozled me, the frightful Jew!”

The relationship between Austria-Hungary and Russia would never recover.

Tensions over the annexation continued to climb into 1909. Italy demanded their own territorial concessions from Austria-Hungary in order to recognize the annexation – Austria-Hungary refused, leading to Italy’s break with them in 1915. Great Britain didn’t see the Serbs as having been harmed, but vocally advocated for the Ottomans, who meanwhile seemed more upset with Bulgaria’s declaration of independence than with losing Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Germany was in the middle of the arguments, attempting to play the public role of peacemaker while in the background throwing their entire weight of support to Austria-Hungary.

The crisis came to a head when Germany threatened to withdraw as mediator and “let matters take their course,” a phrase which Russia knew meant allowing Russia and Austria-Hungary to come to a fighting war. It was not a fight Russia had any chance of winning, and at that point the Tsar’s government made it quite clear to Serbia that they were withdrawing all protests and any military actions that resulted from Serbia’s dogged protest to the annexation would have to be dealt with by Serbia themselves without any Russian support.

Serbia was in no way capable of a fight against Austria-Hungary, and on 31 March 1909, they submitted a formal statement withdrawing their protest.

Serbia recognizes that she has not been injured in her right by the fait accompli created in Bosnia and Herzegovina and that consequently she will conform to such decision as the Powers shall take in regard to Article 25 of the Treaty of Berlin. Submitting to the advice of the Great Powers, Serbia undertakes now to abandon the attitude of protest and opposition which she has maintained in regard to the annexation since last autumn and undertakes further to change the course of her present policy toward Austria-Hungary to live henceforward with the latter on footing of good-neighborliness. Conformable to these declarations and confident of the pacific intentions of Austria-Hungary, Serbia will reduce her army to the position of Spring 1908 as regards to its organization, its distribution, and its effectiveness. She will disarm and disband her volunteers and bands and will prevent the formation of new units of irregulars on its territories.

By the end of April 1909, all the Great Powers had signed the amendments to the Treaty of Berlin and the Bosnian Crisis wound down.

The memory did not fade in Serbia, however, and the anger over the outcome continued to fester as a militant group calling itself The Black Hand began organizing against the Austro-Hungarian Empire and moving the Balkans ever closer to an inferno that diplomacy would not be able to extinguish.

To read more about the Pig War that precipitated the Bosnian Crisis, please click here.

To read more about World War I and the lead up to World War I, please click here.

- February 18, 2021

- Bosnia and Herzegovina , Montenegro , Serbia