From Plague to Vampires

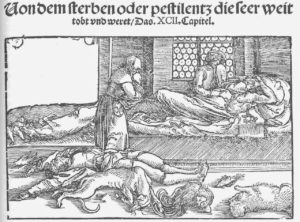

The most popular walking tours in London include strolling by known plague pit sites, where the hundreds of thousands of Londoners who died during the numerous outbreaks of plague are buried. The Black Death killed between 1/3 and 2/3 of Europe’s inhabitants over the course of its random and terrifying outbreaks.

The impact of the Black Death was felt in every corner of society, from the restructuring of ruling classes to childrearing. Methods of land cultivation began revolutionizing, philosophy turned on its head, science began to look at things in new ways, borders of nations changed, and society began a long road toward becoming more urban and developing the entirely new concept of the middle class.

There were outward manifestations of the societal change in Europe as well. Eight centuries later, tourists delight to see the left-over memento mori decorating seemingly random areas, not always understanding the underpinnings that led to widespread use of decor featuring the danse macabre.

The Black Death hit the Middle East in the same time period, and with the same ferocity, as in Europe. It did not, however, cause the same societal shifts. Tombs and graves are not decorated with dancing skeletons. The renaissance of thought in the Muslim world came much later – in the nineteenth century. There was a movement of population from rural to urban centers, but it was not accompanied by increasing standards of greater health and cleanliness or by addressing the plight of the poor with an eye toward trying to solve the problem rather than just alleviate the misery.

In fact, rather than the European shift toward viewing the Plague as a vast judgment of humanity by an angry God, the Muslim world viewed it as a part of the environment, like earthquakes, drought, and locust plagues. It was a part of the natural world – a part that would happen and that just needed to be dealt with in order to move on.

But in the crossroads of Europe, where East meets West, in the Balkans, a completely different method of explaining the source and reasons of the Black Death began to take shape among the peasants and villages. The Plague wasn’t an illness passed somehow through personal contact. It wasn’t the judgment of an angry God. It also wasn’t a part of the natural world. It was, in fact, quite unnatural.

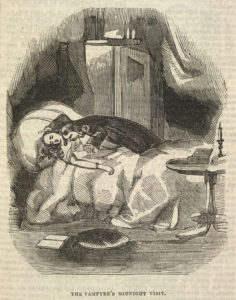

The Black Death came to them from the evil world of the dead, it was an undead phenomenon. It became the vampire, which originated not in the Transylvania of Bram Stoker’s novel, but in the Balkans.

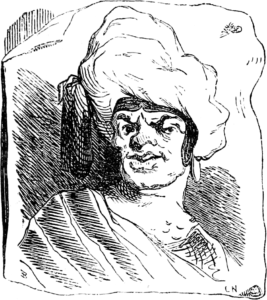

Traces of the vampire legend in Serbian villages exist from the ninth century. It is not the romantic and handsome vampire of the West, but a disgusting and bloated creature oozing gelatinous pulp and blood, boneless, and stinking of death and evil. It is not the cunning strategist with hundred-year-plans of Anne Rice novels, but a zombie-like monster that wandered at night, staying within shadows and hunting with the singular drive of the starving predator. And it began by targeting those the vampire loved in life.

Nor has the vampire mythos disappeared as scientific theory has advanced – in 2012 the Serbian village Zarozje issued a public health warning that their storied vampire was again wandering at night. Suggestions that this warning might have been made tongue-in-cheek and to draw vampire tourism to the area were probably true, but it was also true that garlic sales during this time soared. The truth, as it always is in the Balkans, was a bit more complicated.

Known by several names throughout the Balkans: vrykolakas in Greece, vampirović in Serbia, lampijerović in Bosnia, lugat in Albania, and vukodlaci in Croatia; accounts of vampire outbreaks litter the historic record from before the Ottoman invasion. In fact, the Serbian legal code enacted in 1349, known as Dusan’s Code, directly dealt with the village process of eliminating vampiric infestations by making it illegal to dig up dead bodies and burn them. Most likely the Orthodox Church pushed Dusan into including this law, as anything which challenged their ability to provide absolution from sin (i.e., the fact that a physical action had to be taken to stop the vampire rather than release by priestly ritual) had to be outlawed.

Serbian beliefs for dealing with a vampiric outbreak included using a hawthorne branch to stake the undead (but be careful to only strike once! The second strike awakens the vampire with no harm!) within its grave, beheading, and burning the body.

Nor was Dusan’s Code the only official statement on the legality of dealing with vampires in Balkan history. Several times Ottoman governors had to issue fatwas on their existence and the appropriate manner in which vampires could be dispatched. While vampires were seen as being more of an Orthodox issue, and the Ottomans tried to leave internal matters in non-Muslim religions in the Balkans to their respective church leaders, there was an understanding that the plague of the undead was spreading into the Catholic and Muslim communities as well. People needed to know if it was legal for them to dig up vampiric bodies and get rid of them once and for all.

Even the Austrians got into the act while overseeing Balkan territories in the early 1700s. On two different occasions in 1732 Austrian officials were informed of vampiric outbreaks in Serbian areas and participated in overseeing the diagnoses of vampirism on corpses and then disposing of the now-official vampires in the culturally appropriate manner. It should be noted that the Austrian doctors and officials attending these undead inquests were shocked at the appearance of the accused corpses, agreeing that the standards of vampiric infection had been reached.

And what were the symptoms of vampiric infection according to Balkan folklore? Well, the body would seem that it hadn’t decomposed according to a normal rate. It might be bloated. Instead of becoming ghastly pale, the skin might appear ruddy, and there would be blood in the mouth and on the teeth. There would be no rigor mortis and the body, which had been exercising by night, would be pliant and bendable. The blood in the body would still appear to flow and not have coagulated. And, most importantly (because this is what would start the vampiric investigation) people close to the accused vampire must have been sickening and dying, often after reporting an encounter with the (un)dead. There might also have been reports of sounds coming from the graves of the (un)dead, as well as dirt that appeared to have been disturbed.

Taken in a vacuum, all of these symptoms can sound quite terrifying. People die, and then they decompose. Unless, of course, the weather is freezing cold and the body is buried while the soil acts like a refrigerator. Fresh blood in the mouth when our experience with slaughtering animals shows us that the blood of the dead sinks and coagulates can be terrifying. Unless you have the advantage of modern embalming techniques which warn you that fluids continue to escape the body after death which look quite a lot like blood to the untrained. Bodies bloat after death, yes, but they also burst. Again, unless the soil of the burial is cool enough to slow this process. In that case the body just looks like it has been gorging on the blood of the village. Medieval villagers didn’t understand contagion, so the domino effect of deaths amongst those who were closest also added to a supernatural explanation.

With the Balkan practice of burying corpses between just one and one-and-a -fifth meters below the surface of the soil, as reported by Paul Barber, a bloating corpse pushing the earth away and making the grave look as though it had been disturbed is also easily explained.

And, to be fair, it is likely that the sudden onset of illnesses and death created an emotional reaction that, according to Richard M. Gottlieb, necessitated an explanation that allowed the bereaved to believe that their loved ones were not yet really gone.

“…the vampire was the first to die in an epidemic (e.g. of the plague). His “unrest”, agitation, or lack of being “at peace” causes him to leave his grave and roam the town at night. Again – typically, he visits his family – perhaps his widow – first. This aspect of the vampire tale served to explain to the prescientific peasant’s mind the contagion-by-contiguity-and-contact of the terrifying epidemic of illness and death that he was witnessing.”

But for all the explanations that science has produced, even the most rigidly modern of beliefs might be challenged when out walking in the dark of a village that has no streetlights, where shadows fall where they may under a full moon, and where the sounds of the nearby forest creak and crack and seem to whisper conversations just out of ear shot. And the Balkans has no shortage of these places, even now.

- August 6, 2020

- Bosnia and Herzegovina , Croatia , Serbia